Roots: Family Frauds

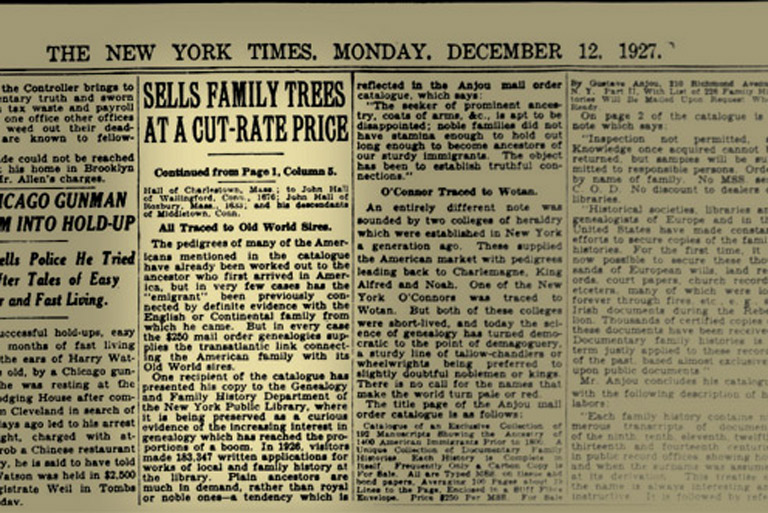

On 12 December 1927, the New York Times published what may have been a first: a front-page feature story about a professional genealogist.

The article “Sells Family Trees at a Cut-Rate Price” detailed the business plans of Gustave Anjou, a “Staten Island Dealer” who was reportedly abandoning the sagging market for patrician ancestries in favour of a more populist approach.

Regrettably, the Times’ unprecedented attention to genealogy was misplaced. The unnamed reporter clearly perceived it as a story about changing consumer tastes, and it was — just not in the way imagined. Anjou was a huckster, a convicted forger in his native Europe, and he was shifting his con from artisanal fake pedigrees for the rich to a high-volume assembly line that would suck in the vast and less discerning middle class.

Advertisement

We now know that Anjou (real name Gustaf Ludvig Jungberg) authored at least three hundred “genealogical” works incorporating false information about as many as two thousand different surnames, possibly more. Some of these lineages — certainly the Church and Freeman families, and probably many others — included kin supposedly born or living in Canada.

These deceptive documents survive on library shelves, in manuscript collections, and no doubt among the cherished family papers of some readers of this magazine. In the past twenty years, unsuspecting family historians have given new life to these old lies by uploading them to the Internet.

Anjou was hardly the first or even the most prominent genealogist to embroider the truth. The Bible, after all, is notable for its suspect lineages. As for the lords temporal, the august Burke’s Peerage published popular misinformation about the origins of the aristocracy throughout the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth.

The mid-nineteenth century in particular was an era of what one commentator has termed “parvenu genealogy,” characterized by specious claims of connections to wealth, nobility, and heraldic entitlement. Many con men of the day, and at least one woman, produced false family trees at a profit for a credulous public. Even the most respected genealogist of the era, Horatio Gates Somerby, whose works can still be purchased on Amazon, sometimes embellished his research to ensure happy outcomes for clients.

We may not be as socially ambitious today, but gullibility is always in fashion. As recently as the 1980s, the Irishman Brian Leese created hundreds of deeply flawed genealogical reports for clients as far away as South America.

Detecting a bogus family tree is not always easy. The noted genealogist and editor Gordon L. Remington has proposed several warning signals, although these are most recognizable in blatant cases.

For example, he cautions against “suspicious, inadequate, or no citations.”

Wise words to be sure, but Anjou was crafty. He would often inundate his clients with references, almost all truthful and relevant. The dirty work, perhaps a link between a real and undistinguished forebear of the client and the equally real and undistinguished descendant of a fabled family, might be “proven” by an obscure document supposedly transcribed in a faraway European archive.

Indeed, Anjou was not above inventing whole parishes to suit his purposes.

Remington also warned against results that were “too good to be true.” However, the precaution may be easier to preach than to practise. Given enough genealogical elbow grease, virtually everyone of European descent can be linked to royalty. So, yes, the finding of royal or noble descent in a pedigree is a warning sign, but not necessarily proof of deception.

Remington’s third stricture concerns reasoning that doesn’t make sense. Are people being born, getting married, having children, and dying at times and in places that seem right? If not, the researcher may be shoehorning individuals of the same or similar names into a single identity, thereby erroneously linking multiple lineages.

Oddly, we’ve come full circle. Time was that genealogical research for most people meant delving into compiled genealogies such as those prepared by Anjou.

Today many family history buffs are once again beguiled by the apparent simplicity of scavenging the work of others. Little more than name collectors, they scour the Internet in search of similar-sounding names in order to graft new lineages onto their Frankentrees. The upshot is that spot tests by one researcher have found that more than half of online family trees are incorrect.

Today the deceptions and the errors are self-imposed. Original records are available, but many prefer to delude themselves rather than to seek the facts. No need for Gustave Anjou in this brave new world.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!