Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

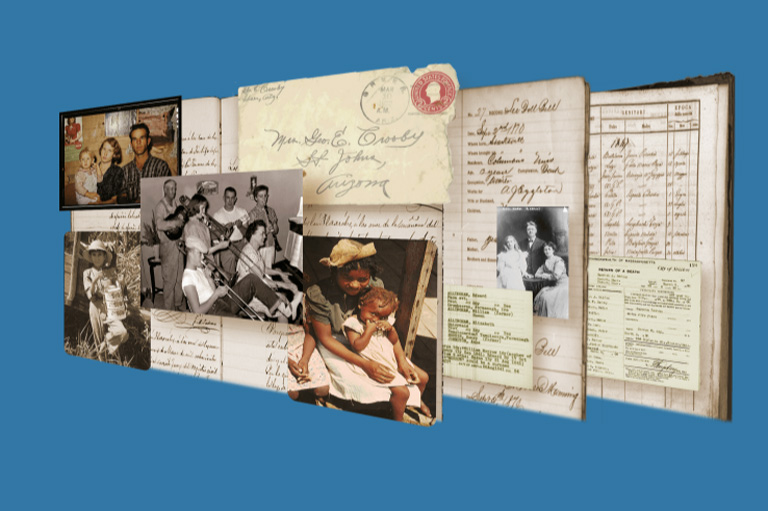

Roots: Family (History) Counselling

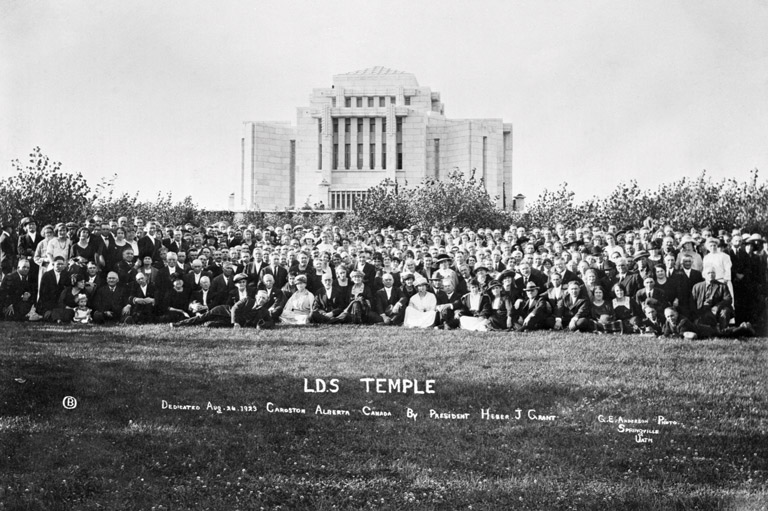

In my days as a newbie genealogist more than twenty-five years ago, I’d just show up on a Saturday morning at a Family History Centre run by the LDS Church and ask for help. Invariably, the volunteers were more than happy to share their expertise. The same was true at libraries, archives, and other institutions across the continent.

Since then there has been an explosion of educational and training resources available to family historians, including in print (books, periodicals, tipsheets); online (tutorials, webinars, YouTube videos, blogs, wikis); from institutions (academic programs, continuing education, distance learning); and via societies and suppliers (workshops, seminars, conferences, and cruises).

No one person could possibly keep up with everything that’s on offer. If confused, simply Google the needed training, e.g.“introduction to genealogy Alberta.”

As someone who has programmed genealogical conferences and workshops, I can say with some confidence that the lecture most likely to elicit a large attendance would be one along the lines of: “How to find eight new ancestors in the next five minutes.” Genealogists are oriented towards results and tend to dismiss the “fluff.”

That’s too bad. My most memorable lessons illuminated principles and processes. I’ll never forget the late Ryan Taylor poring over a problematic census document involving an ancestor of mine. The respected Canadian genealogist’s finger moved down the page, then hovered over a line I’d barely glanced at. “Yes, I think he’s probably the key. Always check the neighbours,” he said with a wry smile.

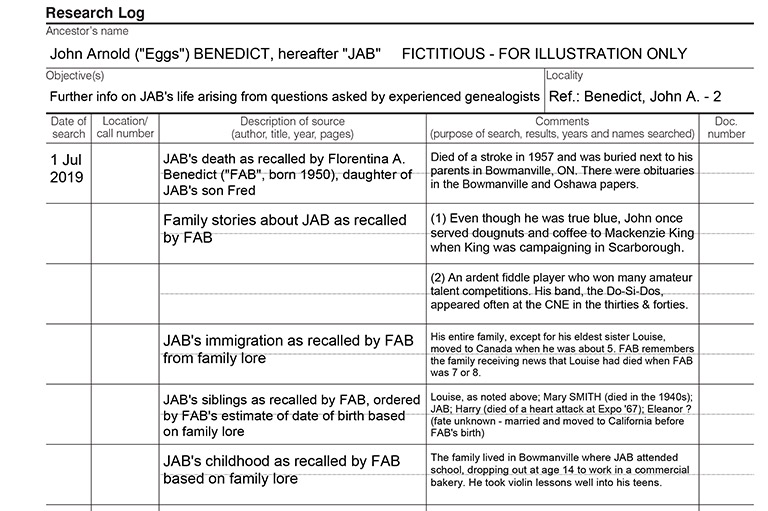

“Always check the neighbours” turns out to be a special case of a broader principle: Extract every item of usable data from your documents. You’d think this approach would appeal to results-oriented, value-conscious family historians. Yet many of us are in such a hurry to confirm our hypotheses that we see only what we’re looking for.

Another lesson from my days as a genealogy student: Dr. Penelope Christensen’s methodology courses for the National Institute for Genealogical Studies, based in Ajax, Ontario. It was there that I learned of the three linkages that must always be proved in every family tree: parent to parent, parent to child, and child to adult.

Most genealogists understand the first two linkages because they typically yield important paperwork. But how many false pedigrees have been propagated because an adult was incorrectly linked with the records of a similarly named child?

So, my advice to fellow genealogists: The next time you attend a conference or a workshop, don’t ignore the fluff. Genealogy is not only about the data. Analysis is equally — perhaps more — important.

Just two of the five elements of the Genealogical Proof Standard deal with sources; three involve the evaluation, interpretation, and analysis of findings.

Not all methodological instruction is flagged as such. Case histories can be a delightful way of absorbing a lesson while enjoying a good story. Yet these classes are usually among the least-attended at any genealogy gathering, on the specious grounds that one doesn’t have any ancestors who lived in the time and place of the case history. That certainly used to be how I thought, too. Of course, what makes a case history great is its resonance with similar situations elsewhere and elsewhen.

In the end, go with the training that suits your learning style. But do take an eclectic view of how your learning objectives can best be met.

Eight ancestors in the next five minutes may sound like a good thing, but only if you don’t spend the next twenty years researching someone else’s family.

And, for non-genealogists, the appropriate response to a helpful family historian is not, “How do you do it?” Sherlock Holmes identified this syndrome back in 1887: “If I show you too much of my method of working, you will come to the conclusion that I am a very ordinary individual after all.” Instead try, “You are a god.” That should do nicely.

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!