Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Nellie McClung and the Great War

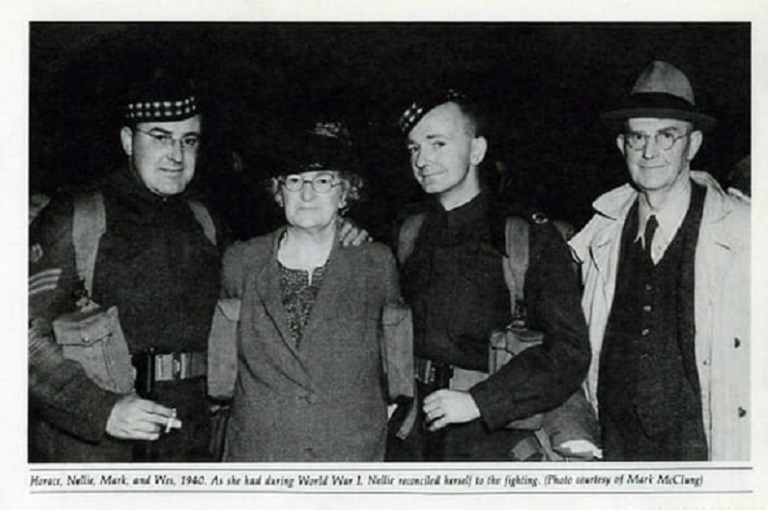

Nellie McClung is well known as one of the Famous Five who fought for Canadian women to be recognized as “persons” under the Constitution.

Along with Emily Murphy, Irene Parlby, Louise McKinney and Henrietta Muir Edwards, McClung succeeded in 1929 in having women become eligible for appointment to the Senate. October 18, 2014, marked the 85th anniversary of that milestone.

Like many feminists of her time, McClung was a pacifist. But her views were challenged when her oldest son Jack enlisted during the First World War.

In a diary entry made December 4, 1915, McClung wrote: “This morning we said good-bye to our dear son Jack at the C.N.R. station where new snow lay fresh and white on the roofs and on the streets, white, and soft, and pure as a young heart. When we came home I felt strangely tired and old though I am only forty-two. But I know that my youth has departed from me. It has gone with Jack, our beloved, our first born, the pride of our hearts. Strange fate surely for a boy who never has had a gun in his hands, whose ways are gentle, and full of peace; who loves his fellow men, pities their sorrows, and would gladly help them to solve their problems. What have I done to you, in letting you go into this inferno of war? And how could I hold you back without breaking your heart?”

With her own son in the trenches, Nellie McClung’s pacificist stance gave way to supporting the war effort, especially the work of the Red Cross.

“I would like to be an out-and-out pacifist,” she wrote decades later, when another world war had erupted.

“I envy the Quakers who go about doing good, in and out of belligerent countries, welcome everywhere with their quiet faces, compassionate eyes, hands of healing and words of hope. But the Quakers, I am afraid, even if their numbers were multiplied a hundredfold, could not bring peace to troubled Europe. Not now. It’s too late…Fire has to be fought with fire, force with force. It is a hard remedy, involving unspeakable horror and waste. No one likes it, but what else can we do?”

Jack McClung survived the Great War and returned to a joyous reception at the McClung house in Edmonton.

“We felt that life had dealt bountifully with us, in letting us have our boy back from the inferno of war,” wrote McClung in her published memoir This Stream Runs Fast.

“From December 1915 to March 1919 he had been away from us, spending three birthdays in the trenches, and now he was back and had come through without a day's illness or even a scratch.

“He had changed, of course, grown taller and filled out, and in many ways he seemed older than either of us.”

Jack McClung never spoke of his war experiences. He also had periods of depression and could be irritable. His mother described his behaviour at a public event not long after the war ended.

“One day, when Jack had come with me to a Board of Trade luncheon, the speaker, a typical solid business man, full of bubbling optimism, greeted Jack with a resounding slap on the back and asked: ‘Well, young fellow, how does it feel to win a war?’

“‘I did not know that wars were ever won,’” Jack said quietly. ‘Certainly not by the people who do the fighting.’ His voice cut like a sharp paper edge and his face had gone suddenly old. Word had come that day of the death of one of his friends in an English hospital.

“Looking back now I can see our whole way of life bothered him. We were too complacent, too much concerned with trifles. He had seen the negation of everything he had been taught, and now here we were going ahead, almost as if nothing had happened.”

Nellie McClung added: “Jack tried hard to adapt himself. He worked long hours and made a name for himself as a student. There were times when he wanted to leave the University and get a job, but we coaxed him to stay and get his degree in Law, and this he did with distinction. He was honoured by his fellow students in many ways, and won a scholarship which took him to Oxford.

“But I knew there was a wound in his heart — a sore place. That hurt look in his clear blue eyes tore at my heart strings and I did not know what to do. When a boy who has never had a gun in his hands, never desired anything but the good of his fellow men, is sent out to kill other boys like himself, even at the call of his country, something snaps in him, something which may not mend.

“A wound in a young heart is like a wound in a young tree. It does not grow out. It grows in.”

Jack McClung would graduate and become a successful prosecutor in Alberta. But his life ended tragically in 1944, when, he shot himself. It was terrible shock.

“For forty-six years we had an unbroken family circle,” wrote Nellie McClung. “Then came the reeling blow and our eldest son, our beloved Jack, was gone — gone like a great tree from the mountain top, leaving a lonesome place against the sky.”

Alcohol and a minor fraud scandal were factors in McClung’s death, but his mother believed his troubles were rooted in the trauma he experienced during the Great War. She ended her book philosophically: “Do not look for safety in this world. There is no safety here. There is only balance.”

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

The war that changed Canada forever is reflected here in words and pictures.