Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Roots: Match Making

The "bestest best boy in the land" recently had his DNA tested. It turns out he’s a beagle mix with a gazillion undifferentiated hound varieties — basically a nose on legs.

Is DNA testing a gimmick or the real deal? That’s the question most often put these days to experienced genealogists by members of the interested public — for example, the readers of this magazine and their ilk. Even dogs are doing it. Should you?

As discussed last time ("Origin stories," October‐November 2016), DNA testing to determine ethnicity has limited value for anyone who knows the origins of all four grandparents (unlike my dog!).

But if you have gaps in your family tree within the past five or six generations, or if you have some other reason to contact distant cousins, then autosomal DNA testing is for you. And yes, it’s the real deal.

Don’t be put off by the jargon. "Autosomal DNA" simply refers to the genetic material in your twenty‐two non"sex chromosomes. This is the DNA you inherited, fifty per cent= from each parent, and, on average, twentyfive per cent from each grandparent, 12.5 per cent from each great‐grandparent, and so on. Actual percentages fluctuate, sometimes greatly, due to randomness in DNA recombination in successive generations.

Other kinds of DNA, which we’ll discuss in a future column, follow different inheritance patterns and cannot be analyzed statistically in the same way.

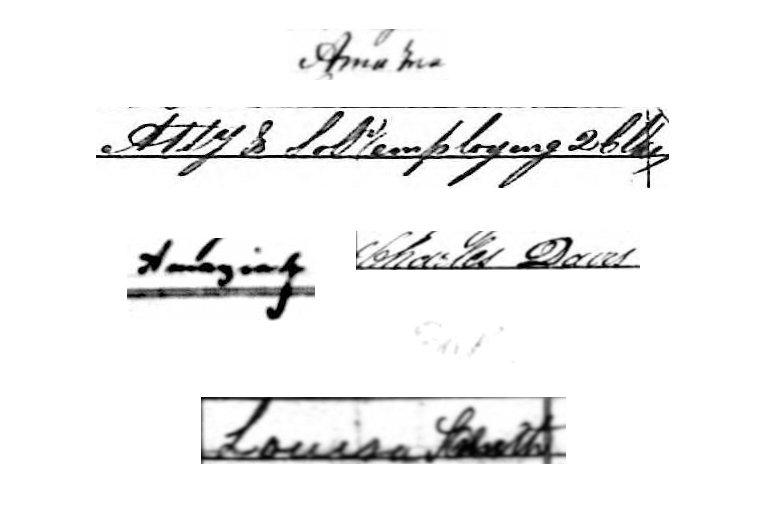

Testing companies look at hundreds of thousands of markers on your autosomal DNA, compare you with every other person in their databases, and apply statistical algorithms to estimate relationships, such as sibling, first cousin once removed, fourth cousin, whatever. You, the consumer, receive a list of your matches, such as the one illustrated, including estimated relationships and ancillary information that varies from one testing company to another.

The results can be magical.

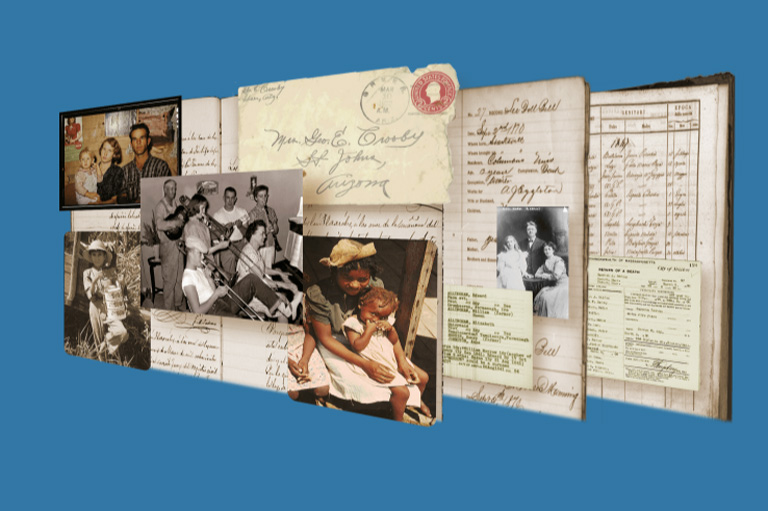

An adoptee identifies birth parents and half siblings she never knew she had (nor they her). A distant cousin sends an antique photo of an ancestor whose face you thought was lost to human memory. New relatives from halfway around the world invite you to visit the homeland.

First, though, you need to contact your matches to compare notes. Don’t be afraid to bug them if you don’t hear back. Failure to respond can be a nagging problem with this kind of research.

Autosomal testing does have other limitations. While false positives are not common if results are interpreted with care, the closeness of relationships can be overestimated between two people who descend from the same culturally or geographically isolated population, such as Ashkenazi Jews, Icelanders, Newfoundlanders, Mennonites, and others. In such cases, the statistical algorithms have difficulty distinguishing between matching bits of DNA that derive from a common ancestor ("IBD," or "identical by descent") and those that are a feature of the source population ("IBS," or "identical by state").

For most of us, false negatives will be a bigger concern. Once we reach back a few generations, we inherit relatively little identifiable DNA from each ancestor and none from some. As a consequence, current autosomal tests miss about ten per cent of third cousins, fifty per cent of fourth cousins, and exponentially higher proportions of more remote relations. Even full-genome sequencing, perhaps an affordable option by 2020, may not improve these statistics by more than a fraction.

How do we fight statistical uncertainty? With weight of numbers. We need to test not only ourselves but also our siblings, first cousins, second cousins, and so on. This way you maximize the odds that someone close to you will match the lost cousins you’re seeking, even if you do not.

Even before testing you and your cousins, though, there’s another group that should be accorded the highest priority: any surviving members of your parents’ generation. Once they’re gone, so is their DNA.

To avoid needless blunders and to answer questions you may have, do some reading before purchasing your first test.

The International Society of Genetic Genealogy provides an information-rich wiki. Next time: some case studies that illustrate the power of autosomal DNA testing — among humans.

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!