Looking for Mrs. Armstrong

Absences in the historical record are often as compelling as the existing evidence, something I discovered in the process of writing and directing my first biography on film. I found that absence can become a space for speculation, for turning over the surviving historical fragments and trying to visualize the pieces that somehow went missing.

This kind of speculation can rapidly escalate into obsession, as I discovered about five years ago when I began catching occasional glimpses of a woman who would later become as familiar to me as the members of my own family. Her name was Helen Armstrong, a working-class housewife and mother of four who rose to the front ranks of labour leadership during the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919, one of the largest worker uprisings in Canadian history.

She would become the subject of my documentary, The Notorious Mrs. Armstrong, but not before I undertook a journey into the past that would take me all over North America and back more than eighty years.

At that time, circa 1919, Helen Armstrong was a clarion voice in the Winnipeg labour movement for the plight of working girls and women. Identifying herself as a women’s labour organizer, she used every means to campaign against the wage inequality and unhealthy working conditions they faced as a minority presence in the industrial work force.

Whether walking the picket line, making her case in the provincial legislature, or facing the police court magistrate, Helen Armstrong was an outspoken and vigorous advocate for all labouring women: laundresses, retail workers, stenographers, telephone operators, hotel waitresses; the list went on and on. In one letter to the deputy minister of labour, she went to hat for the candy-industry girls, citing case after case of poor wages, constant layoffs, and petty persecutions that made “the lives of many of our working girls ... so unbearable that in the end the street claims them as easy prey.”

She added that “we are making a light and have been taken under the protection of the Bakery and Confectionery Workers Union.” It was a typically pugilistic sentiment from a woman who loved to gel into the ring.

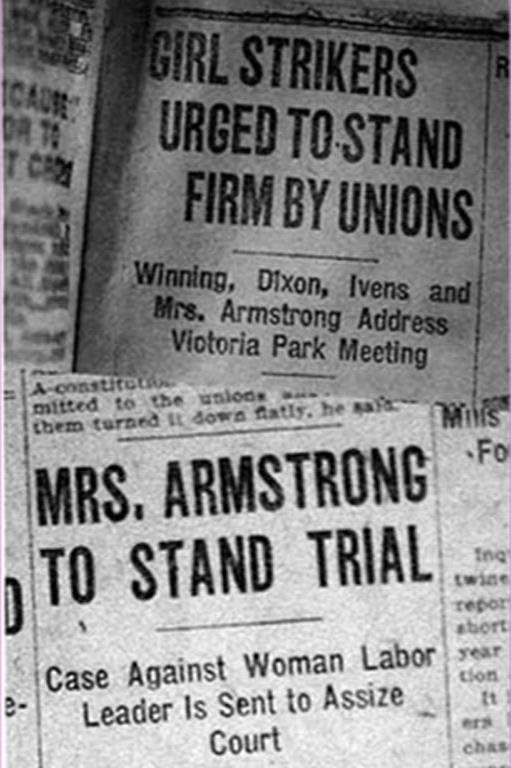

During the 1919 strike, Helen Armstrong’s soapbox-style oratory and street-level agitation were often reported in both the labour press and the mainstream media. In May, the Winnipeg Tribune told its readers:

“At 5 o’clock this morning Mrs. Helen Armstrong started a drive against a number of smaller concerns where women and girls had remained at work. ... At 9 o’clock Mrs. Armstrong said her efforts had been far more successful than she had hoped, and that a large number of new strikers had been added to the rolls.”

In June 1919, the story would get bigger: Mrs. Armstrong to Stand Trial: Case Against Woman Labor Leader is Sent to Assize Court.

Even before the General Strike, Helen Armstrong’s reputation for radical action was well established. In 1917, she rejuvenated the Women’s Labor League and transformed it into an active vehicle for union organization, political advocacy, and the education of women workers on the subject of their own rights.

“A very striking personality is at the head of the Women’s Labor League,’’ wrote an admiring Gertrude Richardson in her column for the Leicester Pioneer. “She is Helen Armstrong, a woman whose ideals are pure and broad.”

Helen was also a woman whose opinions were made loud and clear, as expressed in her letter to the editor of the Telegram in 1917: “Girls have got to learn to fight as men have had to do for the right to live, and we women of the Labor League are spending all our spare time in trying to get girls to organize as the master class have done to protect their own interests.”

A year later, Helen Armstrong was still in the public eye, as a leading figure in the successful 1918 campaign for minimum-wage legislation for women in Manitoba, one of the first two provinces in Canada to enact it. By 1919, Helen Armstrong was already well equipped to deal with the unfolding labour strife, a seasoned campaigner for the rights of her particular constituency.

Until fairly recently, however, Helen Armstrong had devolved into little more than a footnote in the pages of Manitoba history. Throughout the months of research to follow, I would be frequently and forcibly reminded that this woman, so vivid a presence, so powerful a voice in her own day. had been rendered almost invisible in ours.

At the same time, I observed how much scholarship and popular opinion had been expended on an analysis of the male leadership of the strike and their subsequent role in provincial and federal politics.

History, it seemed, took a powerful interest in the “Famous Ten,” those ten men who were arrested for their role as seditious conspirators in the workers’ uprising — in fact, Helen’s own husband, George Armstrong. was one of this select group. There is still at least a passing familiarity with such names as R.B. Russell, J.S. Woodsworth, William Ivens, and John Queen, who later served seven terms as mayor of Winnipeg.

Helen (Jury) Armstrong was born in 1875, the eldest daughter of ten children, to a Toronto tailor. In 1897, she married George Armstrong. When the Armstrongs moved to Winnipeg with their three daughters in 1905 (a son, Frank, was born in 1907) George quickly moved to the forefront of the labour movement. Public notice was first taken of Helen in 1914 when she campaigned alongside her husband in his unsuccessful bid for a seat in the Manitoba legislature.

By 1917, with her daughters old enough to mind the household, she began to take an active role in labour politics on behalf of working women. In that year, she became president of a revitalized Women’s Labor League,presided over the founding of the Retail Clerks’ Union, and took up the anti-conscription banner in the debate over the Military Service Act, against the judgment of most middle-class leaders of the women’s movement.

In 1919, during the six-week Winnipeg General Strike, she was front-and-centre, organizing female workers, picketing, managing a strikers’ soup kitchen, signing up new union members, speaking, and marching, until she ended up in jail on June 24. (She was released four days later.) After the strike, she continued to advocate for working women and in November 1923 ran unsuccessfully for Winnipeg city council.

However, with George blacklisted and unable to find work, the entire family, including their daughters with their husbands, moved to Chicago. After the 1929 Crash, Helen and George returned to Winnipeg, where they remained until the early 1940s. They retired to Victoria, relocated in California to be near one of their daughters. Helen died in Baldwin Park, California, in 1947.

George Armstrong, who was born on a farm in Ontario in 1870, met Helen in her father’s Toronto tailor shop. Trained as a carpenter, he went wherever work was available, which took him in 1897 to Butte, Montana, where Helen travelled to marry him.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the Armstrongs lived in New York, but George regarded New Yorkers as too parochial in their political outlook, and so in 1905 moved the family to Winnipeg, which was then a boomtown for the building trades as well as a hotbed of socialist activity.

He quickly became involved in labour organizing and political activity, running (and losing) three times for a seat in the provincial legislature under a labour banner. He was arrested in the 1919 strike, the only Canadian-born of the “Famous Ten” who were charged for their role as seditious conspirators in the workers’ uprising.

He was sentenced to a year at a provincial prison farm, and released in February 1921. However, in the 1920 provincial election, he won a labour seat in the Manitoba legislature. He took his seat immediately upon his release from prison, but only served one two-year term. With continued political success and construction work difficult to find, George and his family left Winnipeg for Chicago in 1924. He died in California in 1956.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

However, Helen Armstrong has been the object of much less attention, despite the fact that she carried just as much responsibility within the administration of the Labor Temple as any of her male counterparts. As president of the Women’s Labor League, she had become the only female delegate to the otherwise all-male Trades and Labor Council and her views were heard regularly and with respect in those gatherings, according to reports in The Voice and the Western Labor News.

In those years, it was rare for a woman to be so prominent in trade-union affairs, which were just as much a male preserve as any conservative business gathering. Yet during the 1919 strike, regular deputations of women workers brought information from the field to Helen Armstrong, as though reporting to a commanding officer:

“A couple of girls from each box, bag and candy factory, laundry, etc., where the staff is supposed to be on strike, report regularly to room 23 in the Labor Temple, the office of Mrs. Helen Armstrong,’’ the Winnipeg Tribune reported in June 1919.

If imprisonment was the most convincing wav to earn equal time in the history books, well, Helen also got herself tossed into the provincial jail for inciting two women to harass scabbing newspaper sellers. She was arrested on at least two other occasions for her own disorderly public conduct.

The fact that a housewife of respectable working-class origins was incarcerated at all suggests a great deal about her status as a malcontent in the eyes of the civic authorities, one of those unnatural “female bolsheviki” as a Citizen editorial put it. Why would anyone be surprised to discover that Helen’s career as a radical labour activist was a long and storied chronicle?

The most accurate way to describe my interest in Helen Armstrong is both as a student of history and as a filmmaker. As a history undergraduate at the University of Manitoba, I was introduced to historians such as Robert Roberts and Eric Hobsbawm, whose vivid and authoritative writings in working-class history were all the more fascinating because they were chronicling human conditions that had once been dismissed as having minor historical significance.

It wasn’t long before I became aware of the emerging scholarship on another long-neglected front: the realm of women’s history, particularly working-class women’s history. As a student of history, therefore, I believed there was a value in tracing the threads of Helen Armstrong’s life.

First, her crusade on behalf of working girls and women might well provide a fresh perspective on the shattering events of the 1919 strike, as experienced by its only female leader.

Second, an investigation of Helen’s family roots and personal relationships might explain how a working-class mother of four became such a powerful lightning rod for the anger, frustration, and determination of female workers to speak out about their wretched conditions.

Third, to express the turbulence of this period through Helen’s point of view might communicate something meaningful — I wasn’t yet sure what — to others of my generation, perhaps the sense of genuine hope and conviction that fired people up in 1919 and seems so elusive to us now. The more I thought about it, the stronger was my own conviction that Helen Armstrong deserved to be reanimated, so that she could speak her mind again.

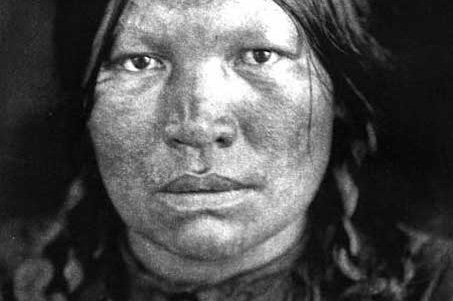

As a filmmaker, however, I quickly realized that I had set myself a very difficult challenge. As powerful as my instinct was about the value of reconstructing Helen’s story, the shortage of materials to support it as a film documentary was, at the outset, nothing short of daunting. I had very little information about her family’s descendants, about her life before the 1919 strike, or her experiences afterward. Worst of all to a filmmaker, I had only three images of Helen herself.

I scoured every conceivable public-domain source for images of Helen. One was the now-famous portrait of the 1919 strike committee with more than fifty men and two women sitting against the wall of the Labor Temple. Helen is the woman on the left, although even this fact was apparently in dispute for a number of years.

The second was a news photo taken of Helen during her campaign for election as city alderman in 1923.

The third was a murky photograph from the pages of the One Big Union Bulletin, a casual image of the convicted strike leaders and their wives picnicking on the grounds of the prison farm east of Winnipeg. Helen and her husband George Armstrong are blurred almost beyond recognition. You can just make out that Helen has one hand draped protectively over George’s shoulder — she is looking off to one side, a barely perceptible smile on her face.

And that was it lor the visual record of Helen Armstrong. Fortunately, newspaper reports of her various exploits were less difficult to track down. I found that Helen Armstrong was steeped in a tradition of political activism, both as the daughter of Toronto tailor Alfred Jury, a respected labour leader with liberal leanings, and as the wile of George Armstrong, a red-hot orator lor the Socialist Party of Canada.

As a tailoress in her lather’s shop, Helen watched her lather preside from his sewing bench over regular gatherings of labour intellectuals, socialists, trade unionists, even the odd businessman, all of whom spent many hours thrashing out the issues of the day.

“It is a tradition among old-timers that everything proposed had to square with principles or Alf Jury would not let it pass,’’ read his obituary notice in The Voice of September 1916. In her own public speeches to labour groups, Helen herself would later acknowledge the importance of her father as an inspiration for her own labour activism.

I pieced together more and more from the available evidence. I read in The Voice (Winnipeg’s organ of labour news) about Helen’s rejuvenation of the Womens Labor League in early 1917, leading the Woolworth’s retail clerks out on strike in May of the same year.

A police court summons from 1917 (evidently a busy time) told me she had been arrested for distributing pamphlets opposed to military conscription to Winnipeg women entering a Next-of-Kin Committee meeting. I discovered, too, that she regularly took food and clothing parcels up to Stony Mountain prison near Winnipeg, where young men were serving out their two years for evading conscription.

There were many other fragments, all fascinating, often startling. Transcripts of the One Big Union conference in early 1919 revealed Helen to be the only woman who stood up and spoke her piece at that historic gathering in Alberta; she challenged the labour men to help educate the women about union activities.

Yet in her own speeches, I found her trying to persuade women to educate themselves so they could organize effectively. The Western Labor News of 1919 described her herculean efforts to organize the Labor Cafe, a soup kitchen that fed thousands of striking women and men. The Winnipeg Citizen, on the other hand, told me she was a female agitator who, by her own admission, had spent time in some kind of lunatic asylum.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Of course, all the papers reported the news of her imprisonment for inciting women strikers to violent behaviour. Taken together, these sources implied two more important facts: that Helen Armstrong was prepared to act on her beliefs, and that when she did so, she didn’t give a damn for anyone’s opinion.

On the other hand, here’s a sampling of what I didn’t know: where she was born, where she spent her childhood, where she went to school, if she went to school, little about her father, nothing at all about her mother, where and when she and George were married, where they lived before coming to Winnipeg in 1905, where they lived in Winnipeg for the first ten years, where her daughters were educated, what kind of relationship she had with them and with her husband, what she thought about socialism, whether it was true that she had been in an asylum, what she thought about housework, what her views were on suffrage, what labour men thought of her, what happened to her while George was in prison for a year, what happened to the Armstrong family in the years following the strike, and most important, who on earth was left that could remember her at all?

The weight of what I didn’t know pressed down like a stone. However, I had now been working for some time with a researcher of formidable talents, Carol Preston of Winnipeg, who offered an inspired suggestion that would eventually open up worlds of possibilities.

She’d located the last known address of Helen’s son, Frank Armstrong, who had died in Winnipeg in the early 1990s, and suggested I try calling the neighbours to find out what they knew about the sale of Frank’s house. Maybe they’d met the relatives involved, with the disposition of his estate. I remember thinking, it’s a long shot, but why not?

I made the phone call to one Bill Burrage, who turned out not only to have lived next door at the time of Frank’s death, but had purchased his house from the Armstrong family’s estate. The executrix was Elsie Friesen, great-niece by marriage to Helen Armstrong. To my growing excitement, Bill told me she lived in Winnipeg.

A visit to Elsie proved to be a godsend — she had a number of Armstrong family photographs, a selection of Helen’s letters and notes, and other documents, including the police summons for Helen’s appearances in court and two complete sets of her handwritten speeches on such topics as suffrage and the importance of women’s political education.

There was also a set of clippings the Armstrongs had saved themselves, mostly about Helen’s activities. Clearly, she had at least some sense of her own place in the annals of labour history.

From these documents, I learned that Helen first woke up to the particular problems faced by women while she and George Armstrong were living in the United States — the first I’d heard of that.

She wrote that “my own early training was in the Radical Liberal school with the early labor leaders of Canada and I heard little of the sex fight — it was all to me a light for wages and conditions and hours of labor. It was not until I married in the U.S. and made my home there that I became acquainted of the fight for Woman’s Suffrage.”

The speech goes on to delineate the entire history of female suffrage through the nineteenth century in the United States. I was to find out later that she referred to the vote as “a club,” a weapon that working-class women needed to make their voices heard. “Without a club, you will not be listened to,” was a favourite call to arms.

Elsie Friesen had something even more important than photographs and documents — she had phone numbers. She was in contact with an American branch of the Armstrong family, a distant cousin named Dottie Dyer.

When I called Dottie, she told me she knew very little about her gret-aunt Helen, but she thought she might have a family photo album belonging to the Armstrong clan in a box in the basement. And, oh yes, maybe I should speak to Helen Cassidy in Phoenix — she might remember a few things too.

Helen Cassidy, it turned out, was Helen Armstrong’s granddaughter and namesake. I flew down as soon as I could to meet her, and realized within minutes that she was an indispensable living link to my subject.

She had lived with her grandmother for a number of years and known her for many more. She could testify to those ephemeral qualities of Helen’s personality that no clipping or photograph could offer, and fill in many puzzling gaps in her history.

The photo album from Dottie Dyer arrived while I was visiting Helen Cassidy in Phoenix. We went through it together, identifying numerous photos of Helen and her family, circa 1880 to 1947. There were pictures of her in every stage of her life: of her sisters, of her children, of her husband, of their friends — there was even a postcard of Karl Marx.

Sitting there, in Helen Cassidy’s kitchen, I realized I was more than halfway home to a documentary that could truly be grounded in visual, textual, and personal testimony to my subject and her world.

From Helen Cassidy I learned about the woman herself. Ma Armstrong, as she knew her grandmother, was a compassionate mother figure to just about anyone who needed help. She informed me that Ma hated corsets and eventually gave up wearing one, and that she despised housework so much that to avoid it she would feign illness and take to her bed, declaring to her long-suffering family that “she wasn’t long for this world.”

This made sense to me — I recollected that in one of Helen Armstrong’s speeches, she departed from the history of suffrage to praise the new labour-saving machines that would one day free women from the drudgery of housework. It was from Helen Cassidy that I finally learned her grandmother had been married in Butte, Montana, a booming mining town where George Armstrong, a carpenter had found work in construction.

She told me that the two of them absolutely adored one another, hut that “you would never know it because they bickered so much over everything.” Especially socialism. Ma was definitely not a socialist, I was told. She had even warned her granddaughter not to make the mistake of marrying a socialist, if she wanted her children to wear shoes.

Just as interesting was Helen Cassidy’s assertion that her grandmother had been a patient at Brandon Mental Hospital, but not because she was a lunatic: she’d had a breakdown after all four of her children came down with scarlet fever at the same time. (The hospital record called it “reactive depression.”)

From Helen Cassidy, I also learned that the Armstrong family was a close-knit one. Helen’s son and daughters took their mother’s constant whirl of activity in stride, although the girls sometimes resented having to do all the household chores while she was out at one of her many meetings.

There was yet another surprise in store in this period of new discoveries: the sudden appearance of Helen Armstrong’s grandson, Bob Waters of Hot Springs, Arkansas. While I was on my own trek into the Armstrong family’s colourful past, Bob Waters was tracing his family roots in a journey that brought him from Arkansas to Winnipeg.

One of his first stops was to the City of Winnipeg Archives, where archivist James Allum, upon learning his identity, hurried to contact me with the amazing news that Helen Armstrong’s grandson was in town. When I met Bob Waters in his hotel room in Winnipeg, we traded bits and pieces of family history back and forth, filling in more spaces between fragments.

He affirmed that his grandmother had indeed become a suffragist in the U.S., citing a well-rehearsed family story that she and a group of female activists had chained themselves to a fence around the White House.*

In Helen’s own correspondence, I discovered her efforts on behalf of women’s rights continued well into the thirties, as she worked to reform the Mothers Allowance Act, which provided support for widows and single mothers. She spent the rest of her time sewing clothes, organizing soup kitchens, and putting food on her own table for anyone who needed help during those terrible years.

Helen Cassidy remembered how her grandfather George used to declare that “the bums put a mark on our fence, so the next bum who came along would know where to go for a free meal.” Bob Waters, too, had fond memories of a warm, maternal grandmother who loved to put on a spread for family and friends.

These family recollections certainly contradicted the loud, aggressive, even hostile persona that was portrayed in reportage of the redoubtable Ma Armstrong.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Read more

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

.jpg?ext=.jpg)