Holding Down the Forts

Parks Canada administers a range of historic forts and fortified places across the country. Here is a sampling of some of them. Each video is from a different perspective: The Rick Mercer Report, a Parks Canada promo, a tourist’s travel video and a news report.

Forts were the focal points of many important developments in Canada’s history. As bases for defence, crossroads of trade, and centres of growing communities, they have been gathering places for generations, whether they were managed by the French or British military, the Hudson’s Bay or North West Company, or the North West Mounted Police. Today they continue to be centres of community life, often contributing significantly to local economies and tourism industries, and bearing witness to Canada’s defining moments.

Defending New France

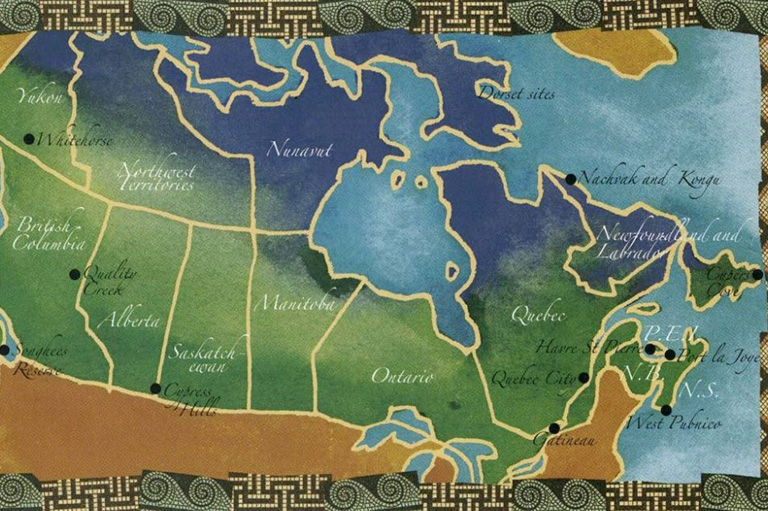

In the early years of colonization, the French constructed — and sometimes captured — numerous forts across North America. They were located as far west as present-day Saskatchewan, as far north as James Bay, and as far south as Florida. They ranged from large, solid stone structures to small wooden trading posts.

The most elaborate is the Fortress of Louisbourg, a gigantic stone complex on Cape Breton Island designed to defend France’s possessions in the New World. The fortified town — which became a busy trading centre connected with the thriving cod fishery — took twenty-six years to build. Despite its size, it was vulnerable to attack and fell into English hands twice. In 1758, after conquering Louisbourg the second time, the English dismantled it. Its rebuilding in the 1960s remains North America’s largest historical reconstruction.

The French also built a string of forts along the Richelieu River, first to defend colonists against the arrows of the Iroquois, and later to defend against the cannons of the English. Fort Saint-Louis, built out of wood in 1655 and later renamed Fort Chambly, was in 1709–11 rebuilt out of stone. The imposing fortress has been restored by Parks Canada and showcases key moments in the history of New France.

As early French fur traders moved inland, they established fortified trading posts along major waterways. However, many of these fell into ruin and their exact locations are lost to history.

Fighting off Americans and rebels

After the conquest of New France in 1759–60, the British either destroyed or occupied the French forts they captured. With the outbreak of the American Revolution, it became necessary to protect against threats from the south. By the time the War of 1812 began, the British had completed a network of forts in the Niagara region.

Chief among them was Fort George, located at present-day Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, and built across the river from American-held Fort Niagara. A complex of log bastions and wooden palisades, Fort George was completed in 1802 and served as the headquarters for the Centre Division of the British Army, a force that included British regulars, local militia, Aboriginal warriors, and freed slaves. The fort was captured in May of 1813 and retaken eight months later. Today, it is a reconstructed National Historic Site.

Other forts from this era include Fort Amherstburg — later named Fort Malden — on the banks of the Detroit River near where the waterway empties into Lake Erie. Built in 1796, it served as the headquarters for British forces in what is now southwestern Ontario and was destroyed by American forces during the War of 1812.

After the war, it was rebuilt, renamed, and repurposed as a centre for British troops during the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837–38. In its later incarnations it served as a “lunatic” asylum and a lumberyard. Today’s Fort Malden National Historic Site includes the remains of earthworks from the 1840s as well as four restored buildings.

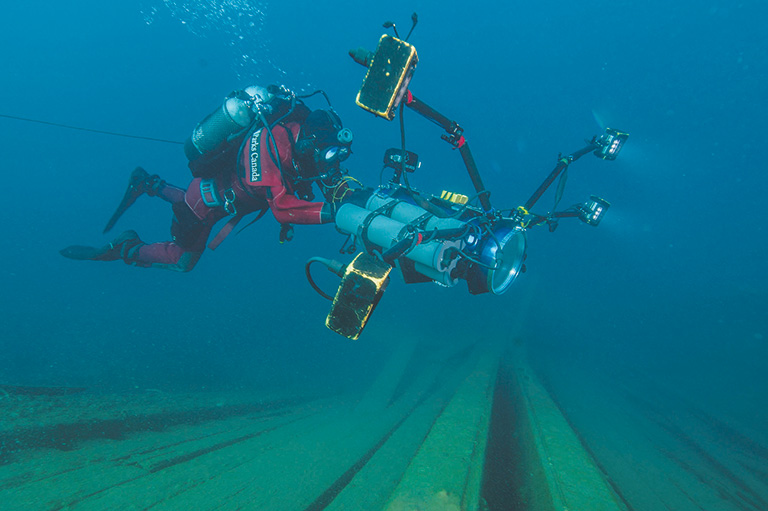

Another War of 1812 fort of note is Fort Wellington, constructed during the war to defend the St. Lawrence River shipping route between Montreal and Kingston from attack by the Americans. Consisting of a substantial one-storey blockhouse enclosed by earthern ramparts, Fort Wellington was expanded in 1838 to include a guardhouse, cook house, latrine, and officers’ quarters. A new Parks Canada visitor centre slated to open in May 2012 will present an enhanced exhibit on the War of 1812, including the display of a preserved British gunboat hull measuring more than fifty feet.

Battling for the fur trade

While independent fur traders were throwing up posts deep in the interior, the Hudson’s Bay Company was sinking huge resources into building massive structures along the shore of Hudson Bay.

York Factory was among the first of these. Constructed in 1684 where the Hayes River flows into Hudson Bay, the post was surrounded by a wooden palisade. In its early years it changed hands several times as British and French traders fought for control of the lucrative trade in beaver pelts.

The HBC retained control after 1713, and the fort became the most important trading post on the bay. York Factory, along with the stone-walled Fort Prince of Wales in Churchill, are retained today as National Historic Sites that commemorate the company’s presence on Hudson Bay.

When the Montreal-based North West Company came on the scene in 1783, it built trading forts inland that seriously cut into the HBC’s profit. In response, the HBC moved into the interior and sometimes set up forts next door to the NWC.

For instance, Fort Espérance in the Qu’Appelle Valley in present-day Saskatchewan was built in 1787 and was the main pemmican depot in the NWC’s continental fur trade. The HBC briefly set up a post across the river from Fort Espérance in 1801, which was destroyed by the Northwesters during the height of the fur wars in 1816. The sites where Fort Espérance stood — it was relocated several times — have been designated a National Historic Site.

While there are no visitor services at Fort Espérance, there is plenty to see and do at some of the other fur trade forts administered by Parks Canada. Lower Fort Garry, near Winnipeg, is the oldest intact stone trading post in North America and a wide range of interpretive programs.

Fort Langley in British Columbia, the site of an HBC fur trade fort that helped established B.C. as a British colony, has activities year-round, such as a corporate adventure program that includes excursions in a large voyageur canoe. At Fort Témiscamingue in Quebec, visitors learn about daily life at an early French fur-trading post.

Bringing order to the Northwest

The opening of Canada’s western and northern frontiers brought inevitable conflict in the form of illegal whisky traders and other types of lawlessness. When the situation boiled over during an 1873 incident known as the Cypress Hills Massacre — the slaughter of more than twenty Nakoda people by drunken American wolf hunters — the Canadian government responded by sending in a paramilitary force.

The North West Mounted Police set up fortified posts across the region. Of particular significance was Fort Walsh, established in 1875 a short distance from where the massacre had occurred in present-day southwestern Saskatchewan. The men stationed there immediately worked to end the whisky trade and patrolled the border to assert Canadian sovereignty.

Aboriginal people stopped in regularly at Fort Walsh for help and advice. And for a while the fort supervised thousands of Lakoda refugees who fled to Canada under the leadership of Sitting Bull. Fort Walsh was reconstructed in the 1940s and is today a National Historic Site.

Another NWMP fort of note is Fort Battleford near present-day Battleford, Saskatchewan. Established in 1876, it played a pivotal role in treaty negotiations with First Nations and served as a base for military operations during the North-West Rebellion of 1885. Today it is a National Historic Site that includes five original buildings and reconstructed stockades and bastions.

Fort Livingstone, near present-day Pelly, Saskatchewan, near the Manitoba border, is notable for being the first NWMP post established in Western Canada. Built in 1874, the ground on which it stood is preserved as a National Historic Site.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Help support history teachers across Canada!

By donating your unused Aeroplan points to Canada’s History Society, you help us provide teachers with resources to engage students in learning about the past.