Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

After the Gold Rush

On the first Sunday of May 2008, an ear-splitting sound rang out over the little Yukon community of Dawson City 280 kilometres south of the Arctic Circle. A siren’s wail blasted along the muddy streets, then echoed off the steep hillside behind the town.

At the time, I was staying at a small, one-storey clapboard house — the childhood home of author Pierre Berton, which he generously donated to the community as a writers’ retreat.

I was there to research and write a book on the 1890s’ gold rush, the last and most northerly gold rush in a century when gold was as important as oil is today.

In August 1896, only a handful of people from the Hän First Nation lived on the cramped mud flat at the confluence of the Klondike and Yukon rivers.

Then seams of gold “as thick as cheese in a sandwich,” according to one observer, were discovered on a creek that flowed into the Klondike River, twenty kilometres from that mud flat.

Tens of thousands of people from all over the globe caught “Klondicitis” and headed north towards the Klondike goldfields.

Hundreds were drowned, killed, or injured as they made the brutal journey up the Chilkoot or White passes, over the ice-capped St. Elias Mountain Range, and through the Yukon’s lakes and rapids towards creeks that boasted names like Eldorado, Bonanza, and Gold Bottom.

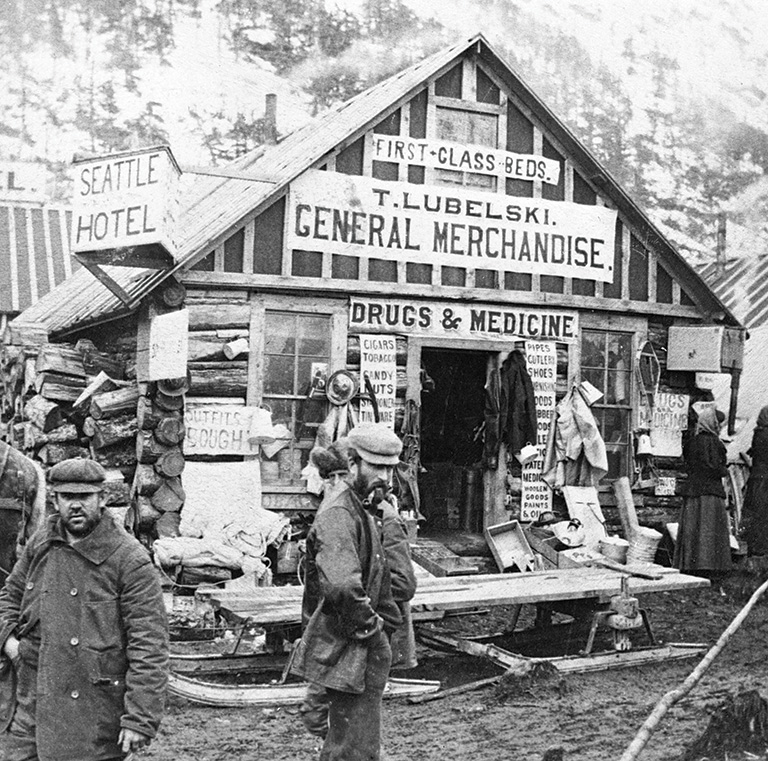

Within two years, the mud flat had become Dawson City — world-famous for whisky, women, and wealth — and the Hän people had been banished from their ancestral fishing grounds.

Meanwhile, the Canadian government was struggling to impose law and order in the boisterous, crowded, squalid, noisy frontier town of 30,000 residents.

Fast-forward to 2008. The siren continued to pierce the thin, clear air. It had been joined by other sounds: dogs howling, trucks bouncing over Dawson’s potholes, the faint sound of human cheering. What was going on?

Then I realized what had caused this commotion, and I was abruptly yanked backwards into the gold rush era. There were no trucks or sirens in the 1890s, but in those days screaming steam whistles, howling dogs, and loud cheers had greeted the same annual event. This was ice-out.

The ice on the Yukon River, which in the dead of winter can be more than three metres thick, had finally broken up.

Along with half of Dawson’s population (today, a year-round total of about thirteen hundred people and two thousand dogs) I ran down to the bank of the Yukon River

The mighty 3,185-kilometre watercourse flows from British Columbia to within a few kilometres of the Arctic Ocean, then curves westward through Alaska until it finally empties into the Bering Sea.

Only days earlier there had been a large expanse of yellowing, potholed ice sufficiently solid to support cars.

Open water had sparkled in the smaller Klondike River, but at the rivers’ confluence the Klondike’s flow was sucked under the Yukon’s frozen surface. Now huge chunks of ice and gallons of icy water surged down the wide Yukon.

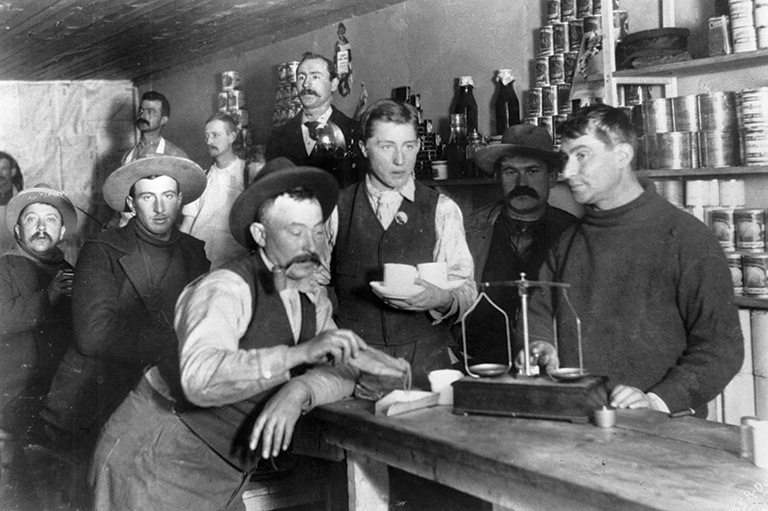

Gold rush veterans left vivid descriptions of the excitement that took hold when winter’s grasp on the northern landscape loosened. With the end of seven long, dark months of isolation, old-timers could look forward to fresh supplies and the next surge of stampeders, eager to stake their claims on the Klondike’s creeks and in Dawson’s casinos.

In May 1897, William Haskell, author of Two Years in the Klondike and Alaskan Gold-Fields 1896–1898: A Thrilling Narrative of Life in the Gold Mines and Camps, stood on the riverbank, watching the “swift current ... result in such pressure that [ice] cakes stand up almost perpendicularly, sometimes ten feet high.”

Bill was one of about a thousand prospectors on the bank that day most wearing the miner’s uniform of rubber boots, patched pants held up by suspenders, grubby neckerchiefs, and battered slouch hats.

All winter, these men had lived on the three Bs — bread, beans, and bacon, with the occasional taste of game if there had been a successful hunt. Steak had replaced sex as Bill’s favourite fantasy, and now his mouth watered for a piece of fresh, juicy beef, with a pile of buttery potatoes on the side.

“The thought uppermost in [my] mind was something more than that of the piece of moose ham which tasted as if it might have been cured during the late War of the Rebellion.”

Today ice-out is a spectacle that everybody enjoys; we stood for hours on the riverbank, watching the powerful flow. But it made little difference to our day-to-day existence, since Dawson now has all the links to Outside (as stampeders called the lands below the Saint Elias Mountains) that it lacked in Bill’s day — a telegraph wire, telephones, a road, an airline, and even WiFi.

A planeload of fresh produce arrives each week. The two Dawson supermarkets carry items such as eggs, fresh pineapples, and pork chops year-round. But reminders of another way of life are never far away. Stubble-chinned prospectors still load vast quantities of canned and dried goods into pickup trucks, so they can disappear for another three-month sojourn in the bush.

For a writer of popular history, the opportunity to see where events actually happened is precious. By the time I arrived at Berton House for my residency, I had read dozens of stampeders’ memoirs with titles like God’s Loaded Dice, With My Own Eyes, and Cheechako into Sourdough.

I wanted to explore the Klondike gold rush by interweaving within one narrative the experiences of six individuals who had left first-hand accounts in letters, books, short stories, journals, or diaries.

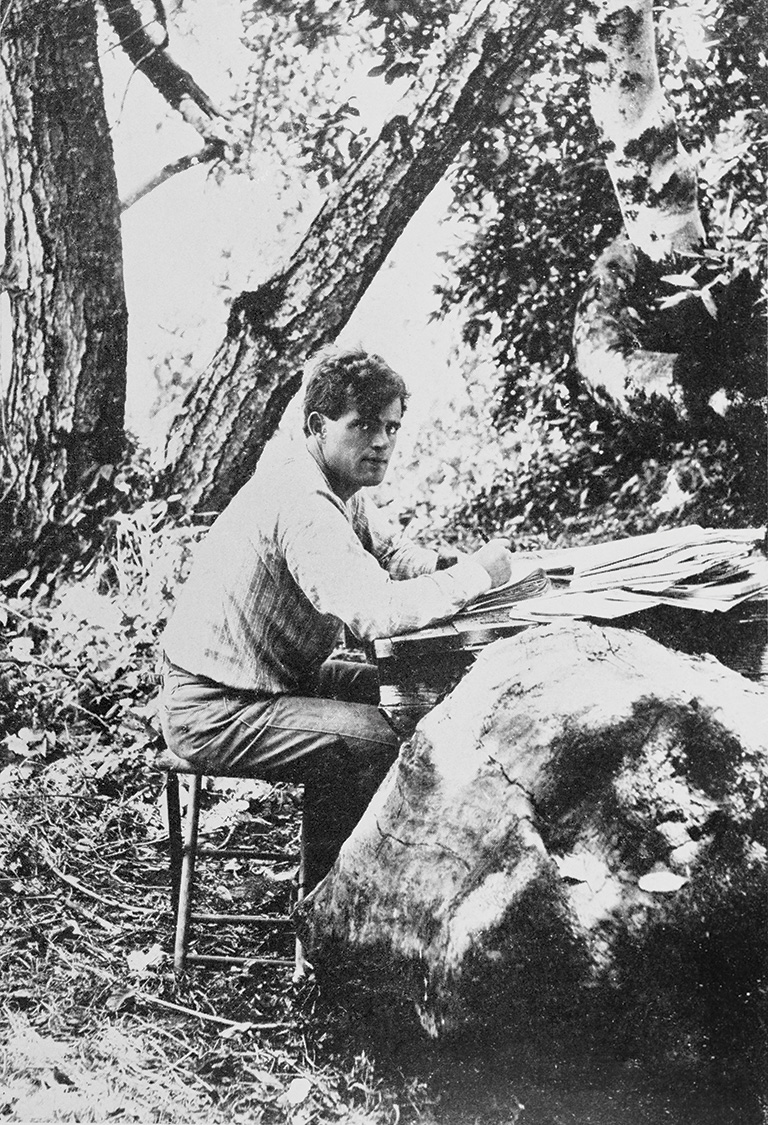

The six included Father William Judge, a selfless Jesuit; Belinda Mulrooney, a feisty and ruthless businesswoman; Jack London, a tough youngster desperate to make his mark on the world; the imperious and imperial Flora Shaw, special correspondent for The Times of London; Superintendent Sam Steele of the Mounties, the barrel-chested lion of the North; and the engaging adventurer Bill Haskell.

Had they not made the journey north, these six people would never have met. Each of them sought riches—although the wealth they found was not always the yellow metal itself.

This would be history from the ground up — the roles individuals play in the larger story of events. But I needed context. I had not yet glimpsed the vastness of the North, felt the giddy sleeplessness triggered by the midnight sun, dabbled my fingers in the Yukon’s chilly waters, nor met anybody who had chosen to live in what Dawsonites still describe, often with grim triumph, as “the end of the road.“

Dawson shares with other small, resource-based towns studded across northern Canada a hostility to the south and a sense of its own uniqueness.

But Dawson is truly unique, thanks to the gold rush. Today, it feels like a shabby film set — a pale version of the raucous rough-and-tumble frontier town of the 1890s. Original buildings give silent testament to past glory. Some of them, such as the Palace Grand Theatre, have been restored by Parks Canada and look infinitely more grand than they did when first built.

Others have been preserved as poignant reminders of the risks of construction on permafrost: St. Andrew’s Church is today a ramshackle wooden structure with a bulging door, lopsided roof, and collapsing walls. Then there are contemporary recreations of gold rush entertainments, staged during the summer for tourists.

Today’s cancan dancers in Diamond Tooth Gertie’s Saloon are as energetic and exuberant as their predecessors, such as the famous sisters Jacqueline and Rosalind (nicknamed Vaseline and Glycerine) who held crowds in thrall in the summer of 1898.

There are more subtle echoes of the past in the local culture, including a whiff of subversion in the air and a resistance to Outside rules. While I was in the North, talk of smoking bans and seat-belt laws elicited guffaws. The heirs of Swiftwater Bill, a legendary gambler during the gold rush, still party prodigiously, especially in the dark winter months.

There were twenty-eight saloons open year-round during the height of the gold rush, giving Dawson its reputation as “the city that never sleeps.“ Today the only bar open year-round is the Pit, which has two rooms. One, the Armpit, is open during the day; the other, the Snakepit, opens at night.

My months in Dawson gave me a sense of place. I saw why even the most hardened gold digger found the landscape mesmerizing. Belinda Mulrooney who was twenty-five years old when she climbed the Chilkoot Pass in 1898, would end up as one of the richest entrepreneurs in the Klondike.

Yet even this tough little Irish-American woman, who snapped at any man who got too close to her, revealed a romantic streak when she contemplated the Yukon landscape.

“The beauty ... you can’t possibly overdo it. It seems to me that every day and every night is different. You just feast on it. You become quite religious, seem to get inspiration. Or it might be the electricity of the air. You are filled with it, ready to go... You couldn’t keep your eyes off the heavens.“

Belinda’s words resonated with me at 2 a.m. on the longest day of the year, as I watched the last rays of the sun paint the undersides of high drifting clouds a delicate rosy pink.

The mountains and rivers and sky were far larger than I had imagined before my arrival in the North. In contrast, some spaces were far smaller.

Most of the cabins that lined Dawson’s streets and the gold-bearing creeks in the late 1890s have dissolved back into the bush, with only a few rotten logs or discarded cans hinting at the lives they once contained. But a few have survived, with their sod roofs, makeshift windows, and claustrophobic dimensions.

Along the road from Berton House is the Jack London cabin — a reconstruction of the cabin on the Stewart River on which the young writer is said to have carved “Jack London / Miner Author” during the bitter winter of 1897.

The Dawson cabin contains half of the logs from which the original Stewart River cabin was built; the other half were shipped to Jack’s hometown of Oakland, California, where another Jack London cabin sits on the waterfront. Jack himself nearly died of scurvy during his year in the North, and he never struck gold. But during his slow recovery he hung out in Dawson’s bars, gathering anecdotes.

Those stories of macho survival would be the basis for many of the stories that, only a few years later, would make him the highest-paid author in North America.

To a modern visitor, the idea of spending five months cooped up with three or four other men in this cramped and squalid space is suffocating. London himself described the experience as spending “weeks in a refrigerator.”

The most dramatic change between then and now is the status of the local First Nation.

The unvarnished racism expressed in memoirs and stories by stampeders like Jack London and William Haskell shocks a modern sensibility.

Raised to disparage strangers who did not look or talk like Anglo-Saxons, hungry prospectors showed nothing but contempt towards the people who for centuries had fished and hunted all over this hostile landscape, had learned the migration patterns of caribou and medicinal properties of vegetation, and knew how to survive the cruel winters.

So what if they were canny traders who had dominated the commerce in fox, bear, and lynx furs with the Hudson’s Bay Company for years? When a Hän fisherman tried to talk to Haskell, the latter hooted with laughter because the Hän language sounded to his untrained ear as though the speaker was “doing his best to strangle himself with it.”

Within a year of the gold strike on the Klondike, the local Hän had been brutally ejected from their ancestral homeland and robbed of the land’s mineral treasures.

Only the Jesuit priest Father Judge regarded Indians as fellow members of the human race. But he was helpless to avert their expulsion to a small reserve known as Moosehide Village, about five kilometres downstream from Dawson. Hän elders spent the next eighty years watching southerners plunder their hunting grounds, pollute their rivers, ship their children off to residential schools, and destroy their way of life.

By the late twentieth century, such actions were recognized as unethical and cruel violations of human rights. Land claims have been settled with most of the Yukon’s First Nations and compensation paid for the traumas of recent history.

Since the early 1990s, the Hän people from the Klondike regions have called themselves the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, and today they constitute about one-third of Dawson’s residents.

One of Dawson’s only modern buildings is the Dänojà Zho Cultural Centre, based on traditional Hän construction methods. There, the 50,000 tourists who visit Dawson each summer can learn a history that is quite different from what is presented in Diamond Tooth Gertie’s Saloon.

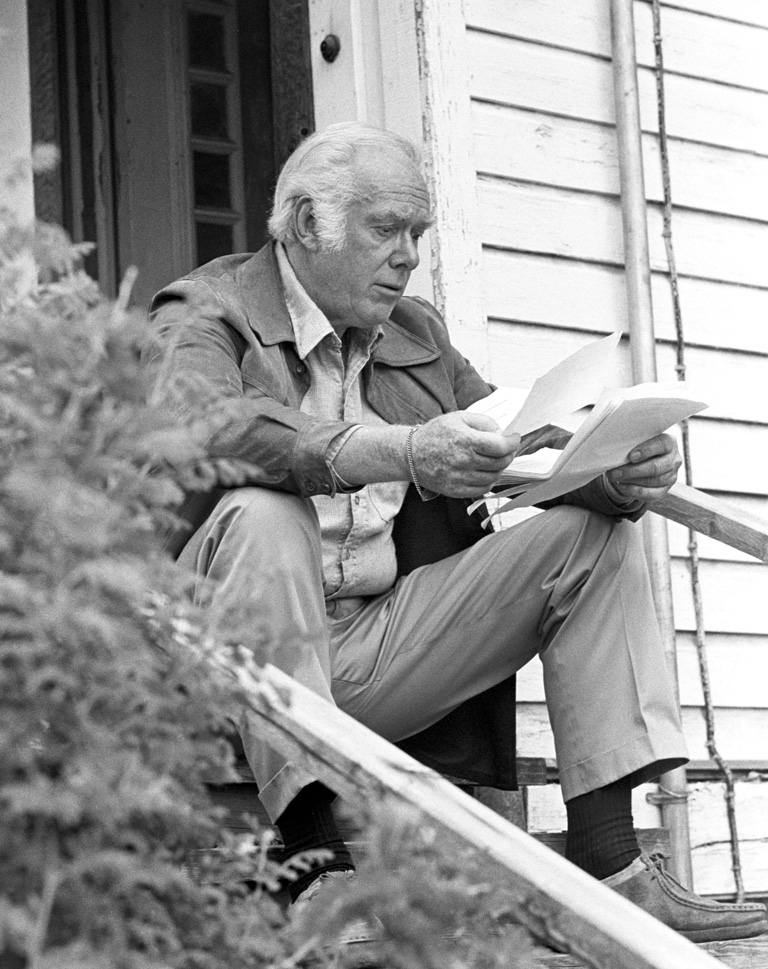

Residence in Berton House made circa 1905. me acutely aware of the challenge I faced. Fifty years ago, in his magnificent Klondike: The Life and Death of the Last Great Gold Rush, Pierre Berton caught the national imagination and revived interest in the Dawson City of the 1890s.

Berton’s grand entertainment teemed with heroes and villains, and whatever I produced would inevitably be compared with his classic. However, narrative history is a multi-layered project, reflecting the priorities and preoccupations of the era in which it is written.

Since Berton’s day, attitudes toward women, First Nations, and the fabric of history itself have changed.

I explore the Klondike story for a new generation, to whom diversity and psychological depth are important.

But my three months in Dawson reminded me that in one respect, Pierre Berton was right. Those who got rich in the Klondike gold rush would always recall it as an epic adventure.

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!