Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

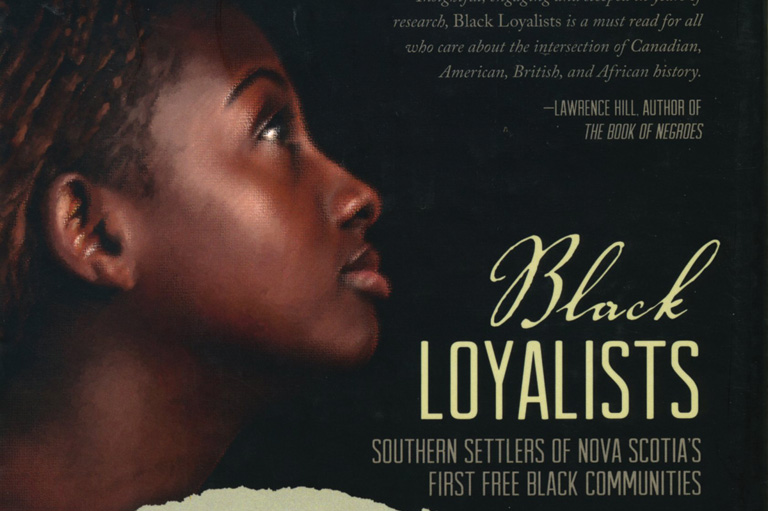

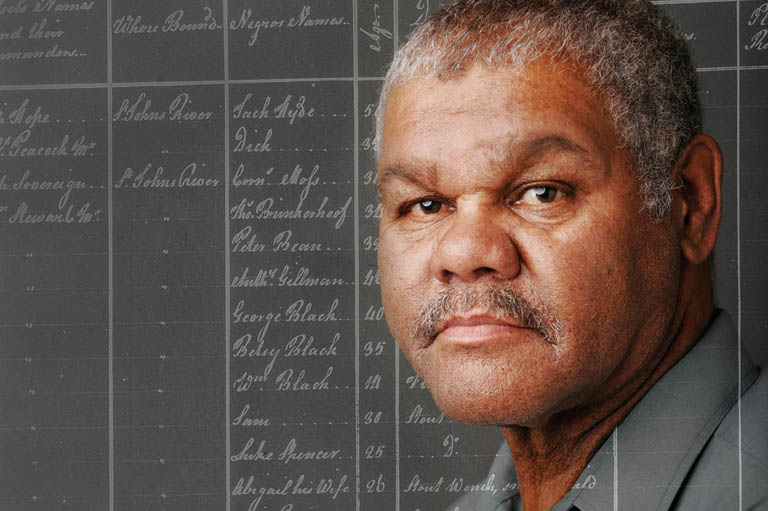

Behind the Book of Negroes

It is not easy to find original documents about the history of blacks in Canada. Indeed, many high-school or university students would come back empty-handed if you sent them to the library in search of material about blacks in the eighteenth century. A few enterprising students might unearth newspaper advertisements for runaway slaves.

For example, the July 3, 1792, issue of The Royal Gazette and the Nova Scotia Advertiser carries a crude sketch of runaway slaves with the advertisement: “Run Away, Joseph Odel and Peter Lawrence (Negroes) from their Masters, and left Digby last evening ... Whoever will secure said Negroes so that their Masters may have them again, shall receive TEN DOLLARS Reward, and all reasonable Charges paid. Daniel Odel, Phillip Earl.”

The truly motivated student might dig up one of the memoirs written centuries ago by blacks who had come to Canada. One, for example, would be the Memoirs of the Life of Boston King, a Black Preacher. Written by Himself, which begins, like most slave narratives, with the circumstances of his birth: “I was born in the Province of South Carolina, 28 miles from Charlestown. My father was stolen from Africa when he was young ...”

But even some of the keenest students might miss a little-known document offering details about the names, ages, places of origin, and personal situations of thousands of blacks who fled American slavery and hoped to find their promised land in Canada.

It is called the Book of Negroes.

The handwritten ledger runs to about 150 pages. It offers volumes of information about the lives of black people living more than two centuries ago. On an anecdotal level, it tells us who contracted smallpox, who was blind, and who was travelling with small children. One entry for a woman boarding a ship bound for Nova Scotia describes her as bringing three children, with a baby in one arm and a toddler in the other. In this way, the Book of Negroes gives precise details about when and where freedom seekers managed to rip themselves free of American slavery. As a research tool it offers historians and genealogists the opportunity to trace and correlate people backward and forward in time in other documents, such as ship manifests, slave ledgers, and census and tax records.

The Book of Negroes did more than capture their names for posterity. In 1783, having your name registered to the document meant the promise of a better life.

Sadly, however, the Book of Negroes has been largely forgotten in Canada. And that is a shame. Dating back to an era when people of African heritage were mostly excluded from official documents and records, the Book of Negroes offers an intimate and unsettling portrait of the origins of the Black Loyalists in Canada. Compiled in 1783 by officers of the British military at the tail end of the American Revolutionary War, the Book of Negroes was the first massive public record of blacks in North America. Indeed, what makes the Book of Negroes so fascinating are the stories of where its people came from and how it came to be that they fled to Nova Scotia and other British colonies.

The document, which is essentially a detailed ledger, contains the names of three thousand black men, women, and children who travelled — some as free people, and others the slaves or indentured servants of white United Empire Loyalists — in 219 ships sailing from New York between April and November 1783. The Book of Negroes did more than capture their names for posterity. In 1783, having your name registered in the document meant the promise of a better life.

As the last British stronghold during the Revolutionary War, Manhattan — where the sacred and the profane mingled so freely that an area teeming with brothels was ironically dubbed “Holy Ground” for its proximity to churches — became a haven for black refugees. Some of the blacks who crowded into the city arrived on their own volition. But others came on the invitation of the British, who twice issued formal proclamations asking blacks to abandon their slave owners and to serve the military forces of King George III.

The first proclamation appeared in November 1775, just months after the Revolutionary War had begun. To attract more support for the British forces, John Murray, the Virginia governor who was formally known as Lord Dunmore, infuriated American slave owners with his famous Dunmore Proclamation:

To the end that peace and good order may the sooner be restored ... I do require every person capable of bearing arms to resort to His Majesty’s standard ... and I do hereby further declare all indented servants, Negroes, or others (appertaining to Rebels) free, that are able and willing to bear arms, they joining His Majesty’s Troops, as soon as may be, for the more speedily reducing this Colony to a proper sense of their duty to his Majesty’s crown and dignity.

Enslaved blacks attentively followed this proclamation, fleeing their owners to serve the British war effort.

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.

The Philipsburg Proclamation came four years later and was designed to attract not just those “capable of bearing arms,” but any black person, male or female, who was prepared to serve the British in supporting roles as cooks, laundresses, nurses, and general labourers. Issued in 1779 by Sir Henry Clinton, commander-in-chief of the British forces, it promised: “To every Negro who shall desert the Rebel Standard, full security to follow within these lines, any occupation which he shall think proper.”

It is no small irony that Lord Dunmore, who issued the first proclamation, was a slave owner himself. The sad truth is that when a number of former British military officers left New York City at the end of the war, they took with them slaves or indentured servants, all of whom had no choice but to follow the men who claimed to own them as they sailed to areas still under the rule of their king.

Nonetheless, in response to the British promises of security and freedom, many blacks escaped from their owners and lent their skills and their labour to an army that had been weakened by smallpox epidemics and by the daily toll of fighting a war on a foreign continent.

If you want to find examples of blacks joining the British war effort, you would only have to scroll through the Book of Negroes to find listings of blacks who had served in a British military regiment called the Black Pioneers. In the ship La Aigle [sic], for example, which left New York for Annapolis Royal on October 21, 1783, all forty-four of the black men, women, and children on board are listed as having served with the Black Pioneers. The children appear to have been with their parents as they served behind British lines:

Jam Crocker, 50, ordinary fellow, Black Pioneers. Formerly servant to John Ward, Charlestown, South Carolina; left him in 1776.

Molly, 40, ordinary wench, incurable lame of left arm, Black Pioneers. Formerly slave to Mr. Hogwood, Great Bridge near Portsmouth, Virginia; left him in 1779.

Jenny, 9, Black Pioneers. Formerly slave to Mr. Hogwood, Great Bridge near Portsmouth, Virginia; left him in 1779.

How did it happen that among the thousands of blacks who huddled in Manhattan — many staying in a shantytown oftents and shacks — ended up filling the pages of the Book of Negroes and sailing to Nova Scotia in the final months of the war?

Certainly, not all American blacks believed in the British cause during the Revolutionary War. Indeed, many fought for the Americans, and the first person to die in the Revolutionary War was a black rebel from Boston by the name of Crispus Attucks. (He was one of five people killed in the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770, and has been frequently named as the first martyr for the cause of American independence.) However, the blacks who sided with the British did so in the hope of finding freedom at the end of the war.

By 1782, as it became apparent that the British were losing the war, and as George Washington, commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, prepared to take control of New York City, blacks in Manhattan became increasingly desperate about their prospects. They had been promised freedom in exchange for service in wartime.

But would the British live up to their side of the bargain?

For a time, it looked as though they would not. When the terms of the provisional peace treaty between the losing British and the victorious rebels were finally made known in 1783, the loyal blacks felt betrayed. Article 7 of the peace treaty left the Black Loyalists with the impression that the British had abandoned them entirely. It said:

Save as much as 52% off the cover price! 6 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital.

All Hostillities both by Sea and Land shall from henceforth cease all prisoners on both sides shall be set at Liberty and His Britannic Majesty shall with all convenient Speed and without Causing any destruction or carrying away any Negroes or other Property of the American Inhabitants withdraw all its Armies, Garrisons, and Fleets, from the said United States.

Boston King, a Black Loyalist who fled from his slave owner in South Carolina, served with the British forces in the war, and went on to become a church minister in Nova Scotia and subsequently in Sierra Leone, noted in his memoir the terror that blacks felt when they discovered the terms of the peace treaty:

The horrors and devastation of war happily terminated and peace was restored between America and Great Britain, which diffused universal joy among all parties, except us, who had escaped from slavery and taken refuge in the English army; for rumour prevailed at New York, that all the slaves, in number 2,000, were to be delivered up to their masters, altho’ some of them had been three or four years among the English.

This dreadful rumour filled us all with inexpressible anguish and terror, especially when we saw our old masters coming from Virginia, North Carolina, and other parts, and seizing upon their slaves in the streets of New York, or even dragging them out of their beds. Many of the slaves had very cruel masters, so that the thoughts of returning home with them embittered life to us. For some days we lost our appetite for food, and sleep departed from our eyes.

In the end, Boston King and his wife, Violet, and three thousand other Black Loyalists did manage to get their names registered in the Book of Negroes, a necessary prerequisite to obtaining permission to sail to Nova Scotia.

To a certain degree, they owed this opportunity to the stubborn loyalty of Sir Guy Carleton, British commander-in-chief in the final days of the war. As historian James W. St. G. Walker at the University of Waterloo has noted, Carleton interpreted the peace treaty to mean that blacks who had served the redcoats for a year were technically free, thus they could not be considered “property” of the Americans. They were free to leave with the British.

Much to the consternation of George Washington, Carleton ordered his officers to inspect all blacks who wished to leave New York and, most importantly, to register those who could prove their service to the British in the Book of Negroes. Carleton told Washington that the British would keep a record of the blacks being removed from New York, and he kept his promise with the meticulously detailed ledger.

The document gives not only the name and age of every black person who sailed from New York under British protection, but, for the most part, it also gives a description of each person, information about how he or she escaped, his or her military record, names of former slave masters, and the names of white masters in cases where the blacks remained enslaved or indentured.

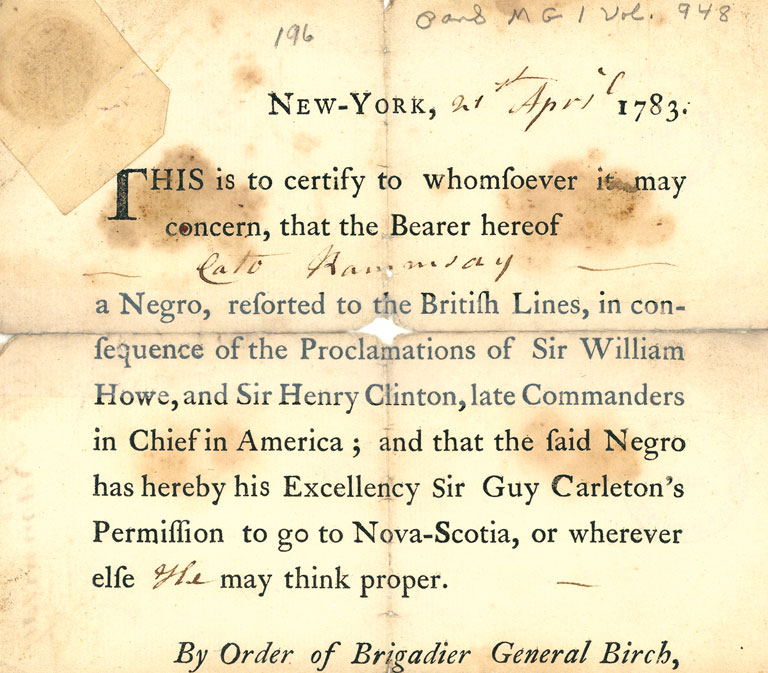

Following is a small sample of passengers listed on July 31, 1783, on the ship L’Abondance heading for Port Roseway (Shelburne), Nova Scotia (“GBC” stands for Brigadier General Samuel Birch’s Certificate, which was proof of service to the British military during the American Revolutionary War).

John Green, 35, stout fellow. Formerly the property of Ralph Faulker of Petersburgh,Virginia; left him four years ago. GBC.

David Shepherd, 15, likely boy. Formerly the property of William Shepherd, Nancy Mun Virginia; left him four years ago. GBC.

Rose Bond, 21, stout wench. Formerly the property of Andrew Steward of Crane Island, Virginia; left him four years ago. GBC.

Dick Bond, 18 months, likely child. Daughter to Rose Bond & born within the British Lines. GBC.

The Book of Negroes also gives the name of the ship on which they sailed, its destination, and its date of departure:

We did carefully inspect the aforegoing Vessels on 31st July 1783 and... on board the said Vessels we found the negroes mentioned in the aforegoing List amounting to One hundred and Forty four Men, One hundred and Thirteen Women and ninety Two Children and ... we furnished each master of a Vessel with a Certified List of the Negroes on Board the Vessel and informed him that he would not be permitted to Land in Nova Scotia any other Negroes than those contained in the List and that if any other Negroes were found on board the Vessel he would be severely punished ...

To qualify for departure by ship to a safe haven well away from the thirteen colonies and the new country they were about to establish, blacks had to prove that they had served behind British lines for at least one year. Many obtained certificates demonstrating their service to the British. But many others who had no such certificates were entered into the Book of Negroes and allowed to sail.

In the end, while frustrated American army officers looked on, 1,336 men, 914 women, and 750 children embarked on more than two hundred vessels waiting to spirit them out of the New York Harbour. Some of the Black Loyalists went to Quebec, England, or Germany, but most travelled to Nova Scotia, establishing communities that exist to this day in places such as Shelburne, Annapolis Royal, Digby, Sydney, and Halifax and its nearby areas.

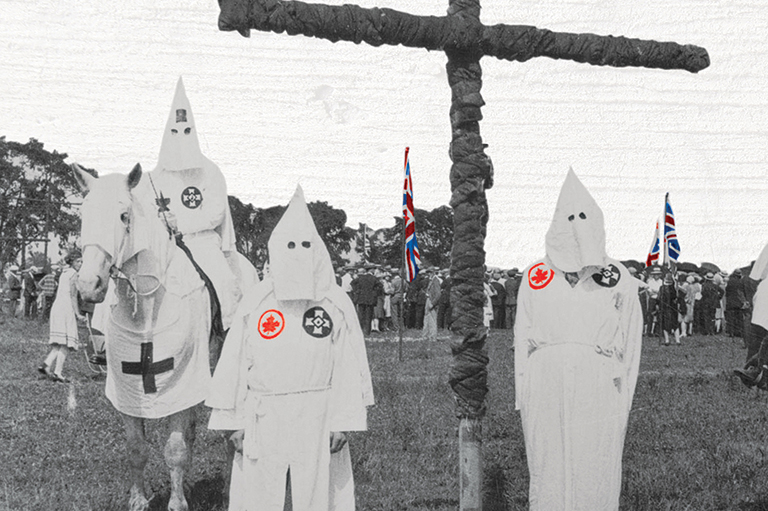

Although many Nova Scotians can still trace their heritage to the Black Loyalists, the blacks who arrived in 1783 did not meet with a fairytale ending. Some never received the land they had been promised in exchange for serving the British during the war, but worse, many were subjected to cruel treatment in the province — confronting a segregated society, the ropes of hangmen, and the first race riot in North America (when disbanded white soldiers drove blacks out of their homes in Birchtown, near Shelburne, in order to secure employment for themselves).

Understandably, more than one thousand Black Loyalists elected to migrate again, just a decade later. Embarking in a flotilla of fifteen ships in the Halifax harbour, they commenced the first “back to Africa” exodus in the history of the Americas, literally navigating past slave vessels as they sailed east across the Atlantic Ocean to found a new colony in Sierra Leone. That voyage, too, was thoroughly documented. But that is another story.

The Book of Negroes is a national treasure and deserves to be considered as such. The Nova Scotia Archives, the Nova Scotia Museum, the Public Archives of Canada, and the Black Loyalist Heritage Society have all helped document the Book of Negroes. Like any great historical document, it offers far too much information to be absorbed in a single sitting. It offers repeated glimpses of the difficult relationship between Great Britain and the nascent United States, and manages to both reinforce and shatter the romantic notion that Canada was a promised land for fugitive American slaves. Many of the people listed in the book travelled “on their own bottom” and free, assuming that their newfound liberty would be protected in Canada. On the other hand, a substantial number of the blacks listed in the Book of Negroes came to this country as the property — slaves or indentured servants — of white United Empire Loyalists. For them, Canada would be a new place to test the chains of human bondage.

Inside the Book of Negroes

(More about the first slide at the top) There are British and American versions of the Book of Negroes. The British version here, which appears to be the original, is written in ink in a large ledger of about 156 pages. For each person entered in the book, details run horizontally across two facing pages, much like these pages, 37 and 38. There are nine columns for information, but not every person has an entry in every column. The columns include the name of the vessel on which the Black Loyalist is travelling, where it is bound, the passengers’ name, age, and description. By modern standards, the descriptions are cruel. “Almost past his labour;” “stout, squat with small child;” and “tall & worn out” are typical entries. There are also columns for the names and place of residence of “Claimants” — a euphemism for slave owners — and for “Names of the Persons in whose possession they are now,” people holding blacks as indentured servants. Finally, the second page for each entry contains “Remarks,” which provide personal details. — L.H.

The (Legislative) End of the Trade in Slaves

Passed 200 years ago, the Slave Trade Act was officially titled, “An Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.” The act rid the slave trade in the British Empire, which had begun about 250 years earlier, during the reign of Elizabeth I. A group opposing the slave trade, consisting of Evangelical Protestants and Quakers, rallied behind the Slave Trade Act. The Quakers had long viewed slavery as immoral. The antislave-trade groups had considerable numbers of sympathizers in the English Parliament by 1807. Nicknamed the “saints,” this alliance was led by parliamentarian William Wilberforce, the most vocal and dedicated of the campaigners. Wilberforce and Charles Fox led the campaign in the House of Commons, whereas Lord Grenville was left to persuade the House of Lords.

Grenville made a passionate speech arguing that the slave trade was “contrary to the principles of justice, humanity, and sound policy” and criticized fellow members for not abolishing it. They put it to a vote. The act was passed in the House of Lords by 41 votes to 20 and it was carried in the House of Commons by 114 to 15, to become law on March 25, 1807. But it would take another twenty-five years before slavery itself became illegal — when parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833.

The British soon set their sights on convincing other nations to end the slave trade, if only to eliminate a foreseeable economic and competitive disadvantage they would be placed in. The British campaign was a large-scale foreign-policy effort. It would take decades to convince some nations to abandon the slave trade. Denmark and the United States banned the trade much later, around 1850. Some small trading nations, such as Sweden and Holland, which had little to lose, responded much earlier.

After the Slave Trade Act was passed in 1807, British captains caught transporting slaves were fined £100 for every individual found on board. Still, the slave trade continued, more deviously than ever. Slave ships in danger of being captured by the British navy would throw many of their illegal passengers overboard to minimize the £100 fine per individual.

The Book of Negroes can be found in the Nova Scotia Public Archives, the National Archives of the United States, and in the National Archives (Public Records Office) in Kew, England. It can also be found online at Library and Archives Canada.

Thanks to Section 25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canada became the first country in the world to recognize multiculturalism in its Constitution. With your help, we can continue to share voices from the past that were previously silenced or ignored.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!