Roots: Finding Family

A few years ago (“Combing for Cousins,” December 2010–January 2011), this column explored the many reasons for tracking down distant, living relatives — such as seeking out old family photos, investigating genetic illnesses, planning a far-reaching family reunion, or verifying a time-honoured tale of a forebear’s emigration. There’s also the potential bonus that a researcher from another line of descent may have missing information about common ancestors.

So how do you go about finding “lost cousins”? Here’s a methodical approach.

Advertisement

Step 1: Determine why you’re looking. For instance, planning a family reunion or tracing an emigrant ancestor? The nature of your descendant search will depend on your goal.

Step 2: Select the ancestor or ancestors whose descendants you want to contact. This will flow out of Step 1. Note that it’s perfectly okay to name “everyone” at this stage if you are just curious.

Step 3: Check into whether your cousins are indeed lost. Perhaps members of your extended family are still in touch with them. You might be surprised to learn who’s on Aunt Ethel’s Christmas card list.

Next we undertake a number of simple searches to ascertain if someone — likely a lost cousin — has already expressed an interest in your ancestor.

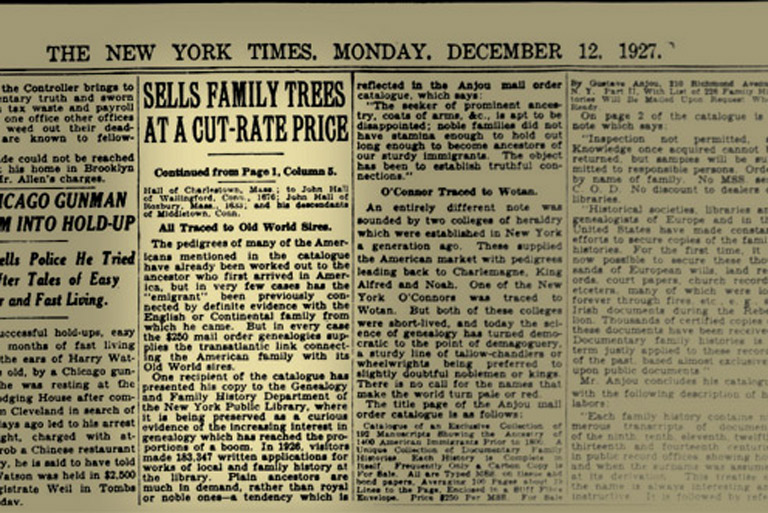

Step 4a: Search at Ancestry and FamilySearch for online family trees containing your ancestor’s name. Repeat for each name you’ve targeted. If you find a match, you will usually be able to send an email message to the person who posted the tree, very likely a lost cousin or someone married to one. A piece of friendly advice: Don’t be a hopeless newbie. Contact your prospective cousin only when details of timing, place, and family composition indicate that there is a real likelihood of a bona fide match.

Step 4b: Google your ancestor’s name. Try variants and play around by adding in the places where you know your ancestor lived.

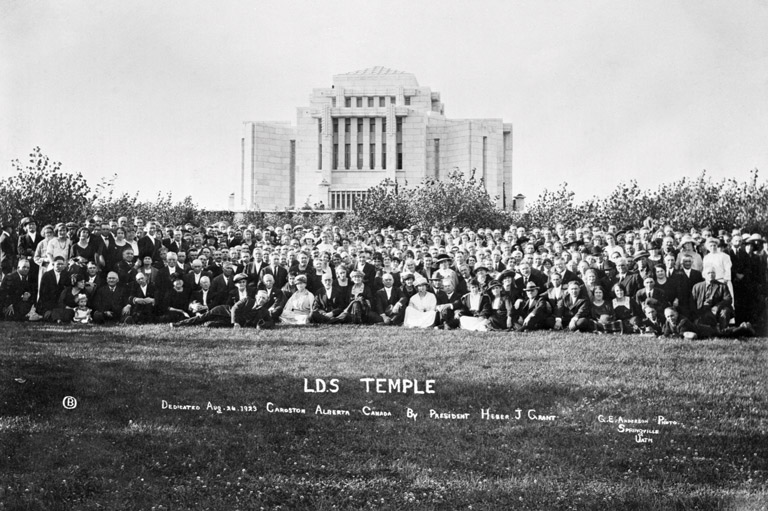

Step 4c: Enter your ancestors’ names on the LostCousins website. Include the relatives on your family tree who were recorded in selected U.S., Canadian, British, or Irish censuses. You will be notified and put in contact with anyone who shares an ancestor.

If you’ve struck out up to this point, it means your lost cousins aren’t looking for you. You will have to actively find them. You need to undertake Steps 5 to 8 below for each ancestor whose descendants you want to seek. Pursue just one ancestor (or husband-wife couple) at a time to keep things manageable. When you exhaust all lines of descent, return to Step 5 for your next ancestor or proceed to Step 9.

Step 5: Using conventional genealogical research methods, identify the children of the target ancestor. For some purposes, the siblings of the target ancestor will do in a pinch.

Step 6: Start bootstrapping your research forward in time. This process is similar to conventional genealogical research in that we use the facts gleaned from one source to point us to more facts from another source, drawing ever closer to our goal with each iteration.

Tracing forward is more complicated than conventional research for two reasons:

- Documents by their nature tell of the past, not the future. So, they’re useful for researching backward in time; less so coming forward.

- Any descendant search will need to navigate the information void created by the unavailability of many records in recent decades due to privacy legislation.

As a result of these constraints, researching forward relies on sources that are generally not subject to privacy legislation, such as newspaper social pages and obituaries, wills, telephone directories, some voters lists, and, in modern times, social media. Researchers in the United States make heavy use of the Social Security Death Index. United Kingdom researchers benefit from a long-standing tradition that births, marriages, and deaths are a matter of public record, not private mystery.

Since researching forward is so difficult, there is a price to be paid for unnecessary steps. For this reason it is often prudent to research the youngest child or sibling of your target ancestor. This may enable you to reach the present with fewer steps.

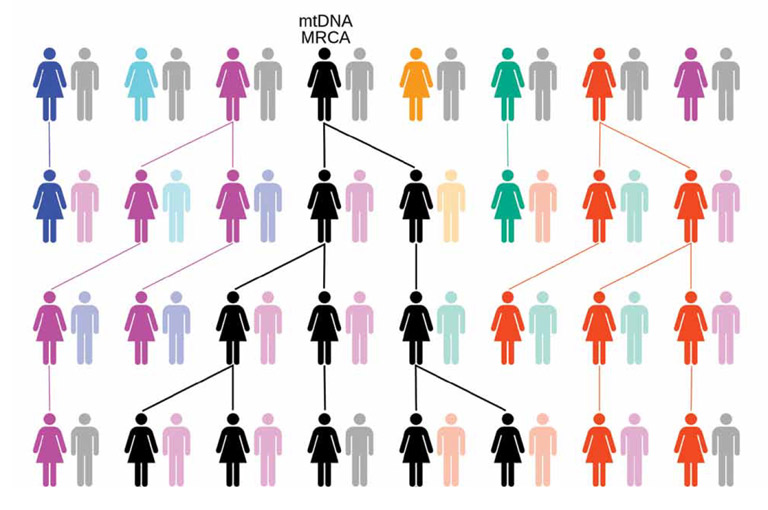

Some authorities recommend that you follow a male line of descent on the grounds that their surnames remain constant throughout life. In a given case, this may be good advice. Still, I normally prefer to follow a female line of descent. Engagement and marriage, the supposed causes of name confusion, actually generate plenty of documents that may be relatively easy to find and quite informative. More importantly, the obituaries of women typically contain extensive family details. And, as they are more likely to live to a ripe old age, you may identify descendants still living today within just a couple of steps.

Step 7: Acquire contact data for the living. You can resort to social media, to Canada 411 (or its equivalent in other countries), to Google, and, if necessary, to people-locating databases, many of which are pay-to-play. The local genealogy society where your lost cousin lives may be helpful. Virtually everyone can be found if you’re patient and willing to pay when necessary.

Step 8: Initiate contact. Some people are thrilled to hear from you. Others don’t want to know about it, no matter how polite, transparent, respectful, and affable you may be. Maybe they worry that you want to borrow money or that your brood of ten will show up next week for an indefinite stay. With luck, you’ll identify several living relatives, and at least one will be happy to share in the adventure.

Step 9: If all else has failed, leave bread crumbs for others to find. For example, a few years ago I prepared a small website about my wife’s missionary ancestors. I wasn’t trying to attract the attention of relatives, but even so a few months later I received an email message from a woman descended from the missionaries through a different branch of the family.

Of course you don’t have to go to the trouble of creating a website; a simple query posted to an online surname or locality discussion group might do the trick just as well.

You can maximize your odds of being found if you upload your entire family tree (having removed all identifying information about living members) to Ancestry, FamilySearch and other sites offering a similar service (the flip side of Step 4b). Distant cousins who share your ancestors may soon be in touch.

Unfortunately, so will “name collectors” — incompetent genealogists who promiscuously graft your tree onto theirs based on no connection more substantial than a shared ancestral name. Don’t be surprised to see your tree proliferating, often incorrectly, across the Web. You may wish to tell these bogus “cousins” to get lost.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!