Bringing the Inuit Home

Photo Gallery

-

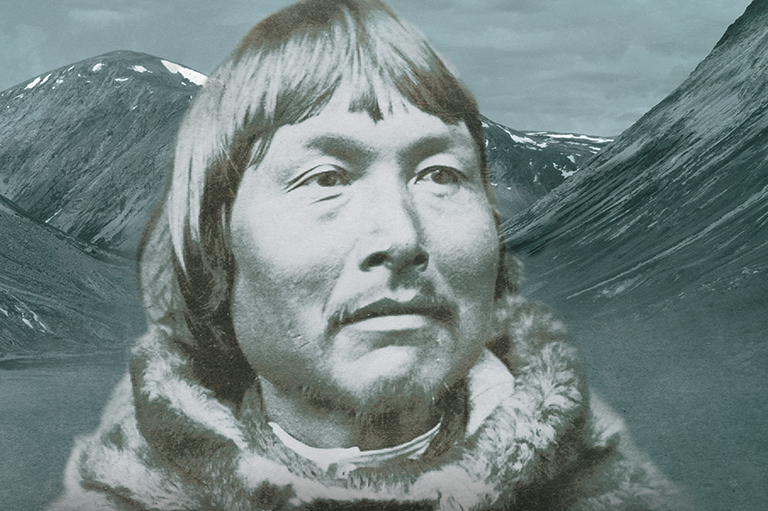

Abraham Ulrikab, as pictured on the cover of France Rivet's book In the Footsteps of Abraham Ulrikab.Courtesy of France Rivet

Abraham Ulrikab, as pictured on the cover of France Rivet's book In the Footsteps of Abraham Ulrikab.Courtesy of France Rivet -

An 1881 image from a poster advertising the Inuit at the Hamburg zoo.Courtesy of Hans-Josef Rollman

An 1881 image from a poster advertising the Inuit at the Hamburg zoo.Courtesy of Hans-Josef Rollman -

An 1886 drawing f the shaman Tigianniak (left), his wife Paingu,and daughter Nuggasak, who were among the Labrador Inuit who toured Europe in 1880–1881.E. Krell

An 1886 drawing f the shaman Tigianniak (left), his wife Paingu,and daughter Nuggasak, who were among the Labrador Inuit who toured Europe in 1880–1881.E. Krell -

A sketch of an Inuit family in a hut. The hut was built as part of the Inuit exhibit at the European zoo.Journal Svetozer

A sketch of an Inuit family in a hut. The hut was built as part of the Inuit exhibit at the European zoo.Journal Svetozer -

An 1880 drawing shows Tigianniak with his dogs outside his tent.Journal Svetozor

An 1880 drawing shows Tigianniak with his dogs outside his tent.Journal Svetozor -

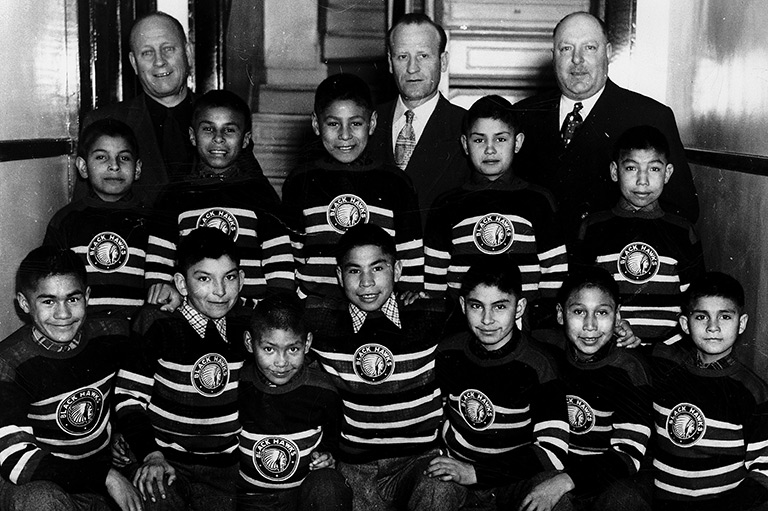

Inuit leader Johannes Lampe, left, with Adrian Jacobsen and Kerstin Bedranowsky, grandson and great-grand-daughter of Johan Adrian Jacobsen, the ship captain who took the Inuit group to Europe in 1880.Courtesy of France Rivet

Inuit leader Johannes Lampe, left, with Adrian Jacobsen and Kerstin Bedranowsky, grandson and great-grand-daughter of Johan Adrian Jacobsen, the ship captain who took the Inuit group to Europe in 1880.Courtesy of France Rivet

I was introduced to the story of the Inuit in Europe in the summer of 2009, during a cruise along the Labrador coast. I was both shocked and fascinated and wanted to know more.

A group of Labrador Inuit — two families and one single man — were put on display in zoos in Germany and France in 1880–1881. All died of smallpox before the tour was over.

Intrigued, I sent emails to museums in Paris asking if, by any chance, they had some of the remains in their collections. The next morning, the reply from the Museum national d’histoire naturelle arrived confirming that it did have a skullcap — along with the fully-mounted skeletons of the five Inuit who died in Paris in January 1881.

I was totally shocked. It had never crossed my mind that the Inuit’s remains could be in a museum’s storage area. A door was now opening to potentially returning their remains to Labrador. But how feasible would it be?

A few weeks later, I was in Paris speaking with museum officials. It was explained that repatriation requests received for identifiable remains must be issued by a descendant, or by the community of origin, and must be channelled to them through our two countries’ external affairs departments.

Since early 2012, my role has been to document the Inuit’s story as thoroughly as possible. My book, In the Footsteps of Abraham Ulrikab, was published in 2014 and reveals what happened to the Inuit’s remains and outlines how they can be repatriated.

I brought up the issue of repatriation with the the Nunatsiavut government (the Labrador Inuit governmental authority), Canada’s Department of Foreign Affairs and the Canadian embassies in Paris and Berlin. Before the Nunatsiavut government officially issues the repatriation request, it needs to determine if the 1880 Labrador Inuit have living descendants, to define its repatriation protocol, and to consult with its population.

A first consultation was held in September 2014, when I visited Nain, Newfoundland and Labrador, to meet with the elders’ committee. At the end of the meeting, Johannes Lampe, the chief, declared that there was a clear consensus that the remains must be brought back.

A few weeks later, Lampe and I headed to Europe with a film crew working on a documentary, “Trapped in a Human Zoo,” scheduled to be aired in February 2016 on CBC's The Nature of Things. Lampe, as his community’s and government’s representative, retraced Abraham’s steps in Hamburg, Berlin, and Paris. But, most importantly, he met with the museums currently holding the human remains of his predecessors.

In June 2015, public consultations about the repatriation protocol were held in each community in Nunatsiavut. The process is therefore well underway.

In 1880, Abraham wrote, “If we can go back to Labrador, we understand that this will be a big story.” This seems to be coming true. The repatriation of the Inuit’s remains will enable Abraham’s community to finally close the loop on this sad chapter of its history.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement