Canada's Great Women

Canada’s History decided to mark the centennial of the first women to win the vote in Canada — in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta in 1916 — by celebrating great women from Canada’s past.

To create our list we recruited a panel of prominent Canadians — former Governor General Adrienne Clarkson; bestselling author Charlotte Gray; historians Michèle Dagenais (Université de Montreal), Tina Loo (University of British Columbia), and Joan Sangster (Trent University); and author and English professor Aritha van Herk (University of Calgary).

Theirs was not an easy task, for how do you define greatness? The list of thirty names the panel came up with is by no means definitive; some of the names are familiar, others are obscure. But what can be said is that each of the great women chosen has in some way made a positive impact on Canada.

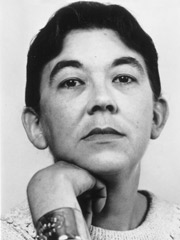

Doris Anderson (1921–2007)

Doris Anderson (1921–2007)

Magazine editor and women’s movement champion. Doris Anderson was a long-time editor of Chatelaine magazine and a newspaper columnist. Through the 1960s, Doris Anderson pushed for the creation of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women, which paved the way for huge advances in women’s equality. She was responsible for women getting equality rights included in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. She authored a number of books, including three novels and an autobiography — Rebel Daughter — and sat as the president of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women. Anderson became an officer of the Order of Canada in 1974 and was promoted to Companion in 2002. She was also a recipient of a Persons Case Award and several honorary degrees. Photo: Barbara Woodley; courtesy of Library and Archives Canada/1993-234 NPC.

Kenojuak Ashevak (1927–2013)

Kenojuak Ashevak (1927–2013)

An inspiring Inuit artist. Born in an igloo on the south coast of Baffin Island, Kenojuak Ashevak’s career as an artist began in 1958 when a government administrator recognized her talent. She quickly became a role model for many other Inuit women, who have become almost as recognized. Among her more well-known works is Enchanted Owl, created for Cape Dorset’s 1960 print collection; it was used on a postage stamp in 1970 to mark the centennial of the Northwest Territories and soon became an artistic icon. Ashevak lived most of her life in Cape Dorset, where she had a large extended family of children and grandchildren. Gracious, composed, and thoughtful, she has been an inspiration and mentor for second- and third-generation Inuit artists. Photo: Ansgar Walk

Emily Carr (1871–1945)

Emily Carr (1871–1945)

A West Coast artist who has been described as “Canada’s Van Gogh.” Born in Victoria, Emily Carr began with few advantages. She studied art in San Francisco, London, and Paris while struggling to fund her education. Embracing the new modernist style, she came home in 1911 and applied her new skills to her favourite subjects — West Coast rainforests and the villages and artifacts of indigenous peoples. However, Canadian critics and buyers were not ready for her work and she abandoned painting for fifteen years. It wasn’t until the National Gallery mounted an exhibition of West Coast art in 1927 that she received the attention she deserved. By the time of her death she enjoyed international renown that has outlasted that of her contemporaries.

Mary Shadd Cary (1823–1893)

Mary Shadd Cary (1823–1893)

First black woman newspaper editor in North America. Mary Ann Shadd was a tireless advocate for universal education, black emancipation, and women’s rights. Born in Delaware, Shadd moved to Windsor in Canada West (now Ontario) to teach in 1851. She soon founded the Provincial Freeman, which was dedicated to abolitionism, temperance, and women’s political rights. During the American Civil War, she went back to the United States as a recruiter of African American soldiers for the Union army. After the war, she moved to Washington, D.C., to teach and to study law, becoming, at age sixty, the second black woman in the United States to earn a law degree. In 1994, Shadd Cary was designated a Person of National Historic Significance in Canada.

Thérèse Casgrain (1896–1981)

Thérèse Casgrain (1896–1981)

Activist, radio host, and politial leader. Despite being brought up in wealth and privilege, Thérèse Casgrain felt that life should be fair to everyone. She helped to found the Provincial Franchise Committee for Women’s Suffrage in 1921 and later hosted a prominent radio program, called Fémina, for Radio-Canada. She became the first female leader of a political party in Canada — the left-leaning Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) — in the 1940s. In the early 1960s, she founded the Quebec branch of the Voice of Women to mobilize women against the Cold War nuclear threat. Later, she became the Quebec president of the Consumers Association of Canada. She did much to better the lives of Canadian women. Photo: Archives nationales du Québec

Ga’axstal’as, Jane Constance Cook (1870–1951)

Ga’axstal’as, Jane Constance Cook (1870–1951)

Kwakwaka’wakw leader, cultural mediator, and activist. Born on Vancouver Island, Ga’axstal’as, Jane Constance Cook was the daughter of a Kwakwaka'wakw noblewoman and a white fur trader. Raised by a missionary couple, she had strong literacy skills and developed a good understanding of both cultures and legal systems. As the grip of colonialism tightened around West Coast nations, Cook lobbied for First Nations to retain rights of access to land and resources. She testified at the McKenna-McBride Royal Commission of 1914 and was the only woman on the executive of the Allied Indian Tribes of British Columbia in 1922. A fierce advocate for women and children, she was also a midwife and healer and raised sixteen children. Photo: Royal BC Museum, BC Archives

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Viola Desmond (1914–1965)

Viola Desmond (1914–1965)

Challenged segregation practices in Nova Scotia. Long before the modern civil rights movement in the United States, a black woman from Halifax took a stand for racial equality in a rural Nova Scotia movie theatre. It was 1946, and Viola Desmond, a hairdresser, caused a stir by refusing to move to a section of the theatre unofficially set aside for black patrons. Desmond was dragged out of the theatre and jailed. While officials denied that Desmond’s race was the root of the issue, her case galvanized Nova Scotia’s black population to fight for change. In 1954, segregation was legally ended in Nova Scotia. Photo: Public domain

Mary Two–Axe Earley (1911–1996)

Mary Two–Axe Earley (1911–1996)

Challenged law discriminating against First Nations women. Mary Two-Axe Earley plunged into activism at age fifty-five, despite considerable opposition from her own community. In the end, she improved the lives of thousands of Aboriginal women and their children. Born on the Kahnawake Mohawk territory, close to Montreal, Two-Axe Earley moved to Brooklyn, married an Irish-American, and had two children. She was later widowed. Because she had lost her Indian status by marrying a non-Aboriginal, she was barred from going back to live on her reserve. For more than two decades, Two-Axe Earley lobbied to have the discriminatory law reversed. In 1985 she was successful. Her efforts benefited about sixteen thousand women and forty-six thousand first generation descendants. Photo: CP/Toronto Star

Marcelle Ferron (1924–2001)

Marcelle Ferron (1924–2001)

Quebec painter and stained glass artist. Marcelle Ferron is the only female artist who signed Les Automatistes’ polemical manifesto, Refus Global, in 1948. Her paintings were hung in all the major Automatiste exhibitions. Her painting technique became progressively forceful with vibrant colours and thick paint. Ferron changed her medium to stained glass after 1964. Her most known stained glass pieces are those in Champ-de-Mars and Vendôme metro stations in Montreal, which were installed in 1968. The Champs-de-Mars window masterpiece is sixty metres long and nine metres high and dapples the station with coloured light. Ferron was also an associate professor at Laval University in Quebec City and became a Grand Officer of the National Order of Quebec in 2000. Photo: Copyright Pierre Longtin

Hannah (Annie) Gale (1876–1970)

Hannah (Annie) Gale (1876–1970)

First alderwoman in the British Empire. When Annie Gale and her husband William immigrated to Calgary from England in 1912 she was appalled by the high costs of housing and food. Determined to change things, she helped to establish a local consumers’ league. A strong advocate for workers and women, she helped to organize the Women’s Ratepayers’ Association and it was this group of women who asked her to run for city council in 1917. Gale won a seat to become the first woman elected to municipal office in the British Empire. She also broke new ground when, while in office, she occasionally served as acting mayor. Gale’s non-partisan approach inspired other reformers, including Nellie McClung.

Anne Hébert (1916–2000)

Anne Hébert (1916–2000)

A writer whose work was universally recognized in all francophone countries. Anne Hébert won all the major awards in France and Belgium and the Governor General’s Award for fiction three times in Canada. She wrote poems, stories, novels, and plays that captured the tumult of human emotions against the backdrop of Quebec history. Hébert began writing at an early age and worked at both the National Film Board and Radio-Canada from 1950 to 1954. From there she went on to live in Paris for almost the rest of her life. The sense of a conquered society struggling to erupt and to break all obstacles is the fierce energy behind the three-dozen works she authored. Photo: lapresse.ca

Adelaide Hoodless (1857–1910)

Adelaide Hoodless (1857–1910)

Educational reformer and founder of the Women’s Institute. Adelaide Hoodless began her public life with the death of her infant son, who had consumed tainted milk. The tragedy inspired her to set about making sure that more women were educated in matters of domestic science, and she began pushing for home economics courses to be taught in Ontario public schools. She was also a powerful force behind the formation of three faculties of household science. Working with Lady Aberdeen, wife of the Governor General, she helped to found the National Council of Women, the Victorian Order of Nurses, and the national YWCA. Photo: Wikipedia

Pauline Johnson (1861–1913)

Pauline Johnson (1861–1913)

Poet and public speaker. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake) is best known for her poetry celebrating her Aboriginal heritage. The daughter of George Johnson, a Mohawk chief, she wrote stories about Aboriginal women and children that were based in an idealistic setting but were more realistic than those written by her contemporaries. Some of her work is included Songs of the Great Dominion (1884) by W.D. Lighthall, the first anthology to include French-Canadian and Aboriginal poetry. Johnson travelled across Canada, the United States, and England to give speeches and poetry readings. Her patriotic poems and short stories made her a popular ambassador for Canada. Photo: Bibliothèque et Archives Canada

Advertisement

Marie Lacoste Gérin-Lajoie (1867–1945)

Marie Lacoste Gérin-Lajoie (1867–1945)

Feminist, social reformer, lecturer, educator, and author. Marie Lacoste was from an early age acutely aware of the inequities faced by women. She was brilliant but had to educate herself through her father’s library because Quebec’s francophone universities were closed to women. In 1908 she helped to establish a girls’ school that would allow young women to pursue higher education. She was a driving force behind the the Fédération nationale Saint-Jean-Baptiste, a francophone women’s organization that championed education, equity under the law, women’s right to vote, and other social causes. Her work paved the way for the rise of the Quebec feminist movement during the Quiet Revolution. Photo: Centre d'archives de Montréal

Margaret Laurence (1926–1987)

Margaret Laurence (1926–1987)

One of the giants of Canadian literature. Born in Neepawa, Manitoba, Margaret Laurence graduated from United College (now the University of Winnipeg) and lived in Africa with her husband for a time. Her early novels were about her experience in Africa but the novel that made her famous — The Stone Angel — was set in a small Manitoba town very much like the one she grew up in. Her work resonated because it presented a female perspective on contemporary life at a time when women were breaking out of traditional roles. Laurence was also active in promoting world peace through Project Ploughshares and was a recipient of the Order of Canada.

Agnes Macphail (1890–1954)

Agnes Macphail (1890–1954)

First woman elected to the House of Commons. Agnes Macphail was born in rural Ontario. While working as a young schoolteacher she became involved with progressive political movements, including the United Farm Women of Ontario. She also began writing a newspaper column. She was elected to the Commons as a member of the Progressive Party of Canada in 1921. Her causes included rural issues, pensions for seniors, workers rights, and pacifism. She also lobbied for penal reform and established the Elizabeth Fry Society of Canada. She later was elected to Ontario’s Legislative Assembly, where she initiated Ontario’s first equal-pay legislation in 1951.

Julia Verlyn LaMarsh (1924–1980)

Julia Verlyn LaMarsh (1924–1980)

Author, lawyer, broadcaster, novelist, and Canadian politician. In 1963, Julia “Judy” LaMarsh became the second female cabinet minister in the House of Commons. She sat in Prime Minister Lester Pearson’s Cabinet as the minister of national health and welfare and minster of amateur sport from 1963 to 1965. During this time the Canada Pension Plan was implemented and the Canadian medicare system was designed. LaMarsh served as secretary of state from 1965 to 1968 where she oversaw the centennial year celebrations, brought in the new Broadcasting Act, which introduced many of the core features of today’s broadcasting policy, and established the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada. Photo: Copyright Health and Welfare Canada

Nellie McClung (1873–1951)

Nellie McClung (1873–1951)

Novelist, reformer, journalist, and suffragist. Nellie McClung was a leader in the fight to enfranchise North American women. Her efforts led to Manitoba becoming the first province to grant women the right to vote in 1916, followed by Alberta and Saskatchewan. After a move from Manitoba to Alberta, she was elected to the Alberta Assembly as a Liberal member for Edmonton in 1921. In the legislature, McClung often worked with Irene Parlby of the governing United Farmers of Alberta party on issues affecting women and children. Both were members of the Famous Five. McClung was also the first female director of the board of the governors of the CBC and was chosen as a delegate to the League of Nations in Geneva in 1938.

Lucy Maud Montgomery (1874–1942)

Lucy Maud Montgomery (1874–1942)

An author with an enduring legacy. Lucy Maud Montgomery is most famous for being the creator of “Anne,” the redheaded orphan from Anne of Green Gables. Published in 1908, the book made Prince Edward Island famous around the world. Montgomery had a consummate literary career, publishing twenty novels, more than 530 short stories, 500 poems, and thirty essays. Raised by strict grandparents, she was a lonely, isolated child, with a vivid imagination. Later, she moved to Ontario, where she struggled with her husband’s religious melancholia, and the challenges of being wife, mother, and manse mistress. She also fought lawsuits with her publisher and with her own ill health. Long after her death, Montgomery’s legacy continues with the enduring popularity of “Anne,” a character so vivid that we can all visualize her immediately.

Angelina Napolitano (1882–1932)

Angelina Napolitano (1882–1932)

Brought domestic abuse to national awareness. Little is known of Angelina Napolitano’s tragic life, outside of the fact that she was an Italian immigrant who in 1911 killed her abusive husband with an axe as he slept, was convicted of murder, and was sentenced to hang. Since abuse could not be used as a defence, the case ignited enormous debate and a flood of petitions asking that her life be spared. It brought the “battered woman” defence into the spotlight and highlighted inequities in the law. On July 14, 1911, the federal Cabinet commuted her sentence to life imprisonment. She was granted parole in 1922 and is believed to have died in 1932. Photo: Lina Giornofelice pictured as the lead character, Angelina Napolitano in the 2005 movie, Looking for Angelina.

Nahnebahwequay, Catherine Sutton (1824–1865)

Nahnebahwequay, Catherine Sutton (1824–1865)

Christian missionary and spokesperson for Ojibwa people. Nahnebahwequay, also known as Catherine Sutton, took issue with the Indian Department in 1857, which prevented First Nations people from purchasing their own ceded land. She travelled to England to present the case to the colonial secretary and the British Crown. A group of Quakers in New York funded her voyage and provided her with a letter of introduction. She was introduced to Queen Victoria on June 19, 1860. The intervention of the British government allowed her and her husband, William, to buy back their land, but nothing was done for other First Nations families. Upon returning to Canada, she continued to argue for the rights of indigenous people. Photo: Copyright Grey Roots Museum, Owen Sound

Madeleine Parent (1918–2012)

Madeleine Parent (1918–2012)

Union organizer and social activist. Late in life, Madeleine Parent was recognized her indefatigable activism on behalf of workers, women, and minorities. But in her younger years she was marked as a dangerous woman and a “seditious” traitor. In the 1940s, Parent organized workers in the massive textile factories of Quebec. She was convicted — and later acquitted — of seditious conspiracy. From the 1950s to the 1970s, she led the Canadian Textile and Chemical Union, and launched historic struggles over workers rights. In her late eighties, Parent continued to speak out on a wide range of social justice issues. In the end, her radical, left-wing ideas not only defined who she was but became her lasting legacy to Canadian society.

Gabrielle Roy (1909–1983)

Gabrielle Roy (1909–1983)

A francophone writer who gifted to Canada some of the most memorable novels of the twentieth century. Gabrielle Roy chronicled hardship and hope, family and estrangement, and the difficulties of love. Born in St. Boniface, Manitoba, in 1909, Roy was the youngest of eleven children in a family without material wealth but replete with stories. Despite hard times, she saved enough to travel to Europe in 1937. There she began writing. She returned to Canada in 1939, and published her first novel — Bonheur d’occasion — in 1945. The novel won France’s Prix Fémina and its English translation, The Tin Flute, won Canada’s Governor General’s Award. She would go on to win two more Governor General’s Awards, as well as other literary prizes.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Charlotte Small (1785–1857)

Charlotte Small (1785–1857)

Explorer David Thompson’s wife and interpreter. Charlotte Small was born at Île-à-la-Crosse, a fur trade post in what is now northern Saskatchewan. She was the daughter of a Cree woman and a white trader with the North West Company. Raised among her mother’s people, her knowledge of both English and Cree made her a valuable companion to Thompson. Married at age thirteen to twenty-nine-year-old Thompson, Small would go on to accompany the explorer as he mapped much of western Canada, covering as much as 20,000 kilometres. Thompson acknowledged that his “lovely wife,” with her knowledge of Cree, “gives me a great advantage.” Their strong and affectionate partnership lasted 58 years and they raised 13 children. Photo: As depicted on the cover of Woman of the Paddle Song written by Elizabeth Clutton-Brock.

Eileen Tallman Sufrin (1913–1999)

Eileen Tallman Sufrin (1913–1999)

Labour organizer and workers advocate. Eileen Sufrin led the first strike of bank employees in Montreal in 1942. However, her biggest battle, and the highlight of her career, was her attempt to unionize employees at Eaton’s, Canada’s largest department store at the time. Of the 30,000 Eaton’s workers across Canada, Sufrin and her team were able to organize 9,000 employees between 1948 and 1952. Despite the low number of memberships, she took pride in knowing that during this time Eaton’s increased salaries, pensions and welfare. Sufrin was awarded a Governor General’s Medal in 1979, one of seven Canadian women honoured on the 50th anniversary of the Person’s Case.

Kateri Tekakwitha (1656–1680)

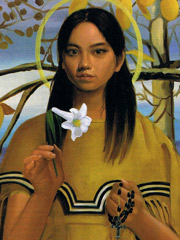

Kateri Tekakwitha (1656–1680)

North America’s first First Nations saint. The story of Kateri Tekakwitha is a story of resilience in the face of colonial incursions, and of a woman who tried to revitalize her traditions and values despite her conversion to Catholicism. Born in 1654 near what is now Auriesville, New York, Tekakwitha was orphaned at age four. At age nineteen, she went to the Catholic mission of Kahnawake near Montreal, where she befriended a group of devout women and devoted the rest of her short life to prayer, penitential practices, and caring for the sick and aged. Miracles were attributed to her shortly after her death, and her gravesite soon became a pilgrimage site. Tekakwitha was canonized as a saint on October 21, 2012. Photo: Dorothy M. Speiser

Thanadelthur (1697–1717)

Thanadelthur (1697–1717)

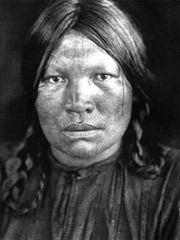

Peacemaker, guide and interpreter for the Hudson’s Bay Company. Thanadelthur was a member of the Chipewyan (Dene) nation who, as a young woman, was captured by the Cree in 1713 and enslaved. After a year, she escaped, and eventually came across the HBC York Factory post, governed by James Knight. Thanadelthur stayed to work for Knight, who needed a translator to help make peace between the Cree and the Chipewyan for trading purposes. Accompanied by an HBC servant and a group of friendly Cree, she went on a year-long mission into Chipewyan territory. She brought the two groups together and — alternately encouraging and scolding them — brought about a peace agreement. The HBC records refer to her as “Slave woman” or “Slave woman Joan.” Photo: This young Chipewyan woman from Cold Lake, Alberta, photographed by Edward Curtis in 1928, was popularized by historian Sylvia Van Kirk as a well-known representation of Thanadelthur.

Marie-Madeleine Jarret de Verchères (1678–1747)

Marie-Madeleine Jarret de Verchères (1678–1747)

A legendary heroine who held back an Iroquois raid. Around the age of fourteen, Madeleine, in the absence of her parents, defended the family fort from a group of Iroquois. There are at least five contemporary accounts of what happened. The most plausible, written by her about seven years after the event, suggest she escaped the clutches of an Iroquois warrior by loosening her kerchief, then rushing into the mostly undefended fort and closing the gate. She somehow fooled the Iroquois into thinking there were many soldiers defending the fort and fired a round from a cannon. The noise alerted other forts in the area and apparently scared off the Iroquois warriors.

Justice Bertha Wilson (1923–2007)

Justice Bertha Wilson (1923–2007)

First woman to be appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada. Born into a working-class family in Scotland, Bertha Wilson trained in law in Canada. When appointed to the high court in 1982, she already had a track record as a justice with the Ontario Court of Appeal, where she was known for her humane decisions in areas such as human rights and the division of matrimonial property. During her nine years on the Supreme Court, she helped her male colleagues to understand that seemingly neutral laws often operated to the disadvantage of women and minorities. She thus helped usher in groundbreaking changes to Canadian law. Photo: Copyright Cochrane Photography

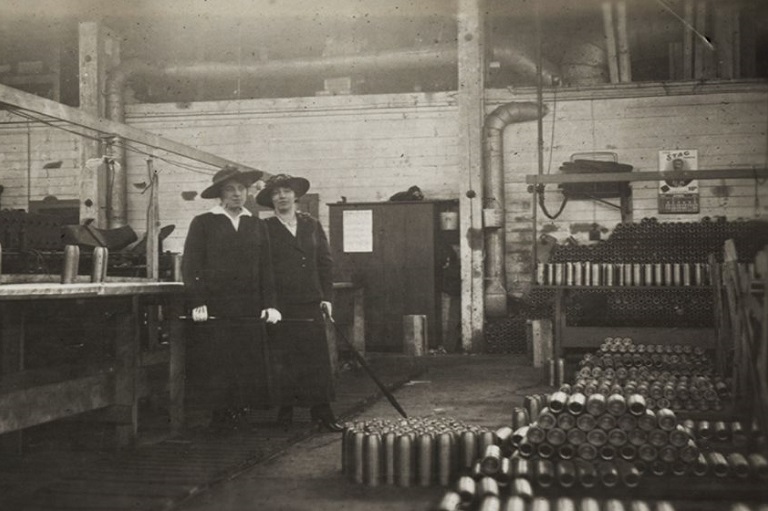

Jane Wisdom (1884–1975)

Jane Wisdom (1884–1975)

One of Canada’s first professional social workers and the first head of the Bureau of Social Services in Halifax. Jane Wisdom completed her initial training and education in social work in New York because there were no schools of social work in Canada. She returned to Halifax in 1916 to lead the newly established Bureau of Social Services. She moved to Montreal in 1921 to complete her studies and lectured in social work. She continued her work in Montreal for eighteen years before moving back to Nova Scotia. In 1941 she accepted a position as the first welfare officer for Glace Bay, which made her the first municipal welfare officer in Nova Scotia. Photo: nsasw.org

Thank you for reading about some of Canada's Great Women.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

.jpg?ext=.jpg)