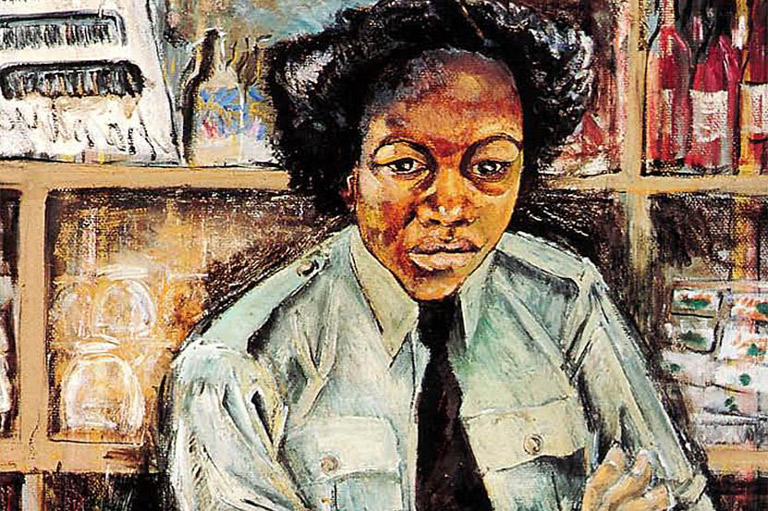

Remembering Mona Parsons

In April 1945, Clarence Leonard, a soldier with Canadian forces liberating northeast Holland, was approached by an emaciated woman who identified herself as Canadian. He was entirely unprepared to hear she was from Wolfville—100 kilometres from his home city of Halifax, Nova Scotia. Imprisoned by the Nazis since 1941, the woman had escaped in March and had walked from Germany to the small Dutch town of Vlagtwedde near the Dutch/German border.

Because her story was so unbelievable, the woman was taken to Canadian Army Rear Headquarters in Oldenburg, Germany, where she was to prove she was not a spy. There was little need for her to speak in her own defence, as she encountered several officers with the North Nova Scotia Highlanders whom she had known while a student at Acadia University. They readily vouched that the woman was the former Mona Parsons of Wolfville, married to Amsterdam businessman Willem Leonhardt, and daughter of retired Col. N.H. Parsons of Sunny Brae, Pictou County, Nova Scotia.

How a cultured woman known in the best Amsterdam social circles came to be a filthy, shoeless refugee suffering from septicemia and found on a road near Vlagtwedde was the question for which many wanted an answer.

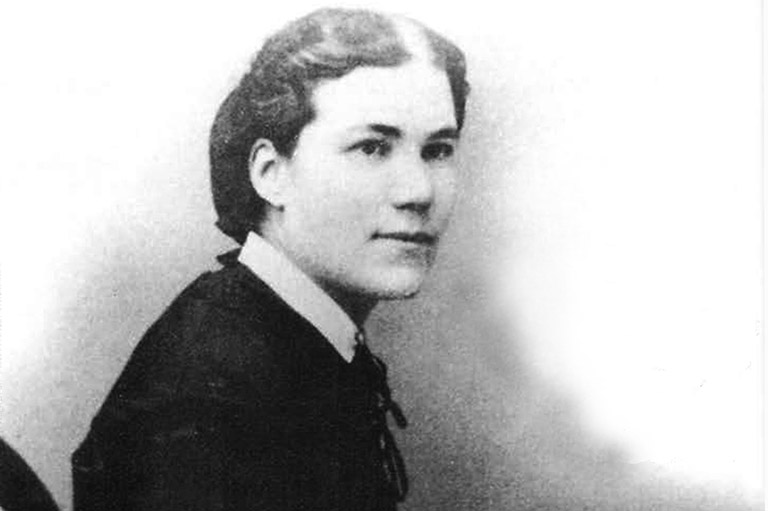

Mona Louise Parsons was born in Middleton, Nova Scotia on February 17,1901, the youngest of three children and the only daughter born to Colonel Norval and Mrs. Mary Parsons. (Colonel Parsons was to distinguish himself in the First World War as commanding officer of the 85th Battalion, mobilized out of Camp Aldershot, Nova Scotia in May 1916). When Mona was two, the family had moved to Wolfville—another small town in Nova Scotia’s orchard-laden Annapolis Valley. Mona attended the Acadia Ladies’ Seminary, dedicated to the “genteel, Christian education” of young ladies. She excelled in music, painting, and expression.

Mona aspired to be a serious dramatic actor, and after graduating in 1920, attended the renowned Currie School of Expression in Boston, taught drama for two years in Arkansas, then returned to Nova Scotia to attend Acadia University, where she pursued campus drama activities.

Growing restless, she decided to try her luck auditioning in New York, and found work as a chorus girl in a touring production of the Ziegfeld Follies. The role fell short of her desire for a serious dramatic career. When Mona’s mother became ill in 1927, Mona tore up her contract and returned home to nurse her mother.

After her mother’s death in 1930, Mona’s ambitions changed. She returned to New York to study nursing and worked after graduation as a private nurse in the Park Avenue offices of a specialist originally from Nova Scotia. She established herself as an independent career woman in one of the world’s most exciting, cosmopolitan cities.

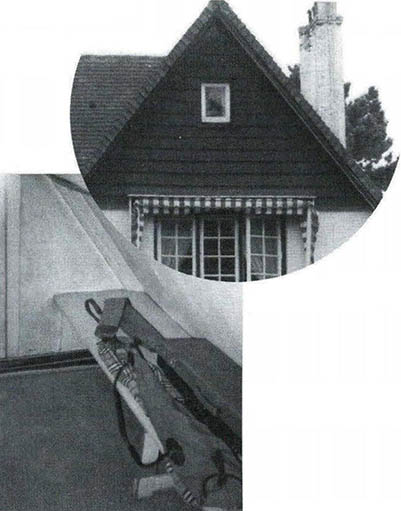

In February 1937, Mona’s brother introduced her to a business associate, Willem Leonhardt, a suave, sophisticated, and wealthy Amsterdam businessman touring the United States and Mexico. Willem and Mona intrigued one another. After a five-month courtship, they were married in the Netherlands. In 1938, they built a large, well-appointed house in Laren, near Amsterdam, and called it “Ingleside.”

The Leonhardts’ happiness was a bright spot in the shadow cast over Europe by Nazi Germany. Mona had planned to visit family in Canada during the summer of 1939 but, concerned that she might not be able to return to her home in the Netherlands, cashed in her ticket, despite Willem’s objections. Their second wedding anniversary, September 1, 1939, coincided with the Nazi invasion of Poland. Two days later Britain declared war on Nazi Germany.

Willem was greatly concerned that Mona, a Canadian citizen and British subject, would suffer more than he would if Holland came under Nazi rule. But she steadfastly refused to leave, and together they vowed to continue with their lives. When the Nazis occupied Holland in May 1940, however, the Leonhardts decided to take action.

In the early days of occupation, the Dutch people were numb and demoralized. As the initial shock wore off, people began to organize themselves to resist Nazism, whatever the consequences. Mona and Willem joined a small network of people helping downed Allied airmen to slip out of occupied Holland. The relative lack of formal organization was both a help and a hindrance. That, and the small number of people then involved, made resistance activities difficult to detect at first.

At this early stage, resistance activity was organized into various cells or groups. To limit risk, only a few people knew the names of all those involved in a single group. Mona and Willem were only members of one of these groups and as such took the risk that the people in charge were trustworthy. If they were not, the Leonhardts would pay with their liberty or their lives. Nonetheless, they offered Ingleside as a safe house in the network to smuggle Allied airmen out of Holland.

For a time, Mona and Willem’s house remained one of the safest, located as it was about a half-hour drive from Amsterdam. With its long driveway, their home was very private, its extensive grounds surrounded by trees. The building itself was large, especially for two people, and the vacant servants’ quarters in the attic made ideal accommodations for airmen in need of refuge.

By the summer of 1941, as the Nazis became more vigilant, smuggling airmen out of the country became increasingly difficult. The men often had to remain in one place for several days, where once only a few hours had been necessary. In September 1941, Mona and Willem were invited to dinner with friends, the Brouwers, in Amsterdam. They knew that the occasion was more than a social one. Dirk Brouwer, a prominent architect, had taken great pains to convince the Nazis that he was neutral, if not in fact a sympathizer. His ruse had helped many airmen safely exit the Netherlands. He had two British flyers whom he wanted to accommodate while safe passage was arranged.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The airmen accompanied the Leonhardts back to Ingleside to await word from their contact. Days passed and, after a week, they moved on. Despite the unusually long stay, things seemed to have gone smoothly. When several of the Leonhardt’s associates were arrested a few days later, Mona and Willem were sure they had escaped detection. Returning from an appointment one day, however, Mona found that Germany’s special security force, the SS, had made calls to the house.

Convinced that her acting skills would persuade the SS of her innocence and buy some time for her husband, Mona sent word to Willem not to return home. When the SS arrived just after 5 P.M., Mona played the part of the gracious hostess, offering drinks and cigars. But the men, tiring of the game after an hour, told Mona she would have to accompany them to Amsterdam for further questioning. Little did Mona realize, as Ingleside’s heavy wooden front door closed behind her, that she would not see her house again for nearly four years.

At Weteringschans Prison, Mona’s captors employed various interrogation techniques, from bullying and threats, followed by an offer to return her to her beautiful home and fine clothes in exchange for information. When physical force and interrogation met with stony silence or an icy calm that bordered on contempt, the Nazis appeared to give up. They transferred her to Amstelveense Prison and virtually ignored her for the next month and a half. She smuggled out notes, asking about her cat, Wimpy (that being her pet name for her husband—the Leonhardts owned two dogs, but no cats). She soon received a message that although the cat had run away twice, he was safe. Content that her husband was still free, Mona waited.

Then, around 8 A.M. on December 22, Mona was taken from her cell to the Carlton Hotel on Vyzelstraat. There, in a ballroom that held many happy memories of her life with Willem, she was tried for the crime of helping Allied airmen evade capture. The young German soldier provided as her counsel spoke neither English nor Dutch, and Mona spoke no German. A second German was found who could speak a little Dutch, but before they had a chance to discuss the case, the trial began. Mona attempted to follow the proceedings, but she needed no German to understand the hatred emanating from the prosecuting attorney. Writing after the war, Mona described him as in his thirties, and that he

typified the arrogant Nazi officer seen in Hollywood movies. He was a tall, repulsive man with cold, pale blue eyes, stringy colourless hair and heavy thick glasses. He could have had a monocle. He seemed so full of hate, I doubt if he was even pleased with himself. He appeared to have a grudge against the whole world and his immediate target was me.… My answers and my determination not to display any emotion plainly infuriated him. When he became overly abusive, the judge called him down.

Mona, who had given up trying to follow the proceeding, was staring out the window when a phrase caught her attention—todstrafe—death sentence. From the time she had decided to become involved in the resistance, Mona knew that her activities might lead to this, and she was prepared:

I knew all eyes were on me, expecting me to burst into tears. I was determined not to humble myself before any of them. As I left the courtroom, I put my heels together and bowed toward the judge, the prosecutor and my German counsel, who were standing together in a group. Guten morgen, meine herren, I said. My action took them by surprise. They stared at me with their mouths open. After they had stopped gaping, they returned my greeting. The judge followed me from the courtroom and approached with outstretched hand.

Save as much as 52% off the cover price! 6 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital.

The judge congratulated her on her composure and advised that she might appeal her sentence. Rather than death, she might get only life imprisonment. She launched an appeal to General Franz Christiansen, the highest-ranking German general in Holland. He was a friend of some German friends of the Leonhardts, and Mona decided she had nothing to lose by mentioning this in her letter. She languished in a death-row cell at Amstelveense Prison for twenty-eight days before receiving the reply that Christiansen had granted her appeal.

In early January, she was taken from her cell and ushered to an office to await transport to Anrath Prison, near Krefeld in the German Rhineland. While Mona waited to be taken to the railway station, three male prisoners were brought into the office. Mona glanced at them—one looked familiar. As she looked more closely she was stunned to realize that the thin man by the window was Willem. He had dyed his hair and coloured his skin in an attempt to disguise himself, but had not evaded capture. She ran to her husband and, embracing him, had just enough time to exchange brief words before the guards wrenched them apart.

Up to this time, she had derived strength from the belief that Willem was still at liberty. Badly shaken, she became terrified that he would be executed or, worse, abused until he died. There was nothing to do now but hope and remain determined to survive. Mona described her years in Nazi prisons as “an ugly memory” of monotonous tasks, deprivation, and frequent sojourns in solitary confinement. But despite the efforts of the Nazis, masters of degradation and dehumanization, the political prisoners were often sources of inspiration to others in the camps—women who endured the brutality and harshness without breaking.

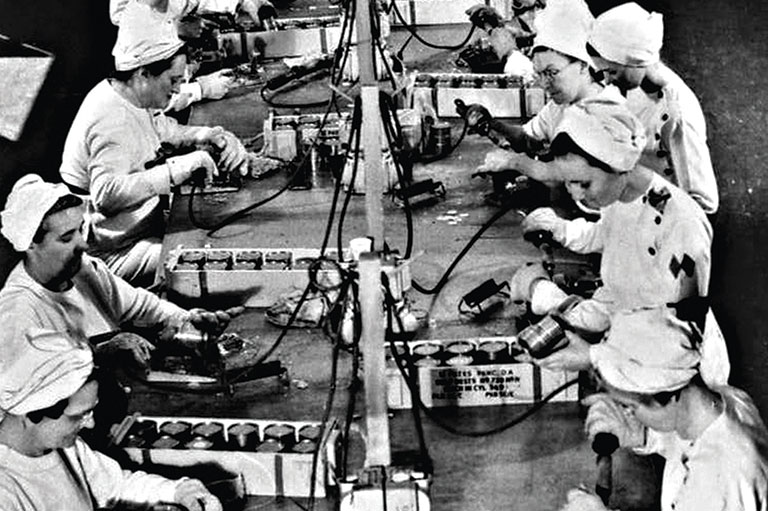

In September 1944, Mona was moved from Anrath to Wiedenbriick camp in which were housed more than 200 female prisoners of war of various nationalities. The women were put to work in a wood factory, making wings for aircraft. The work was as monotonous as the knitting and the construction of bomb igniters done at Anrath, and, in women deprived of basic nutrition, the splinters caused many infections.

Mona was again moved in February 1945, this time to Vechta prison camp. Here she was put to work knitting socks, repairing uniforms, and peeling potatoes. The only reward in this work was the rare opportunity to sneak small pieces of raw potato into her mouth and smuggle pieces back to women in the cells. It was in Vechta that Mona made the acquaintance of a twenty-two-year-old Dutch baroness. Mona would later describe Wendeline van Boetzelaer as her “companion and guardian angel in a memorable flight for freedom.”

Late on the night of March 23, troops under General Montgomery’s command pushed across the Rhine near Wesel in “Operation Plunder.” Further south, a similar assault had been launched by troops under the command of General Patton. Montgomery’s attack was supported by waves of bombers, twenty-five divisions, 3,000 guns, and a quarter ton of ammunition. Vechta (also the location of an aerodrome from which were launched some of the night fighters that plagued Britain, a military hospital, and a transfer point for Nazi troop trains) was one of the Allied targets.

Early on the morning of March 24, Vechta prison camp inmates were awakened by the pounding of bombs dropped from Allied planes. The aerodrome was heavily damaged. The men’s prison took a direct hit; all occupants were killed. The women’s prison was thrown into confusion. Guards panicked and threw open the gates. Many women ran for freedom, but when the smoke and dust settled, only two remained at liberty: Mona Parsons and Wendeline van Boetzelaer—and they had every intention of remaining free. The baroness had escaped twice before and headed west for the Netherlands, but both times she had been apprehended. This time she decided to go north before heading west.

The two women had to devise a plan quickly. How could they make their way through Germany without being detected? Wendy spoke German fluently and knew the country’s geography well. After years of being denied the right to speak English, Mona spoke German, but with a distinct Canadian accent. Too risky for her to attempt to pass herself off as a native. Wendy suggested that each should concentrate on her particular strength. Wendy would do all the talking, and Mona (twice Wendy’s age) would draw upon her training as an actor and assume the role of Wendy’s aunt: a mentally handicapped woman with a cleft palate. Had it not been for the fact that their lives were at stake, their “rehearsals” would have been comical. But as Mona wrote later,

There was nothing funny about our situation. We were far behind the Nazi lines and at any moment might be recaptured. If that happened, our lives wouldn’t be worth a plugged pfennig. Wendy said, “If they catch us this time, we’ll be shot.”

The two women were convincing in their aunt-and-niece disguises, and were able to find food and lodging on several occasions. But there were hair-raising moments too, such as the time they accidentally hailed an SS policeman while looking for a place to spend the night. He offered to take them to his home, and knowing that refusal would invite suspicion, they passed a harrowing night. Eventually they made their way to a small village near the Dutch/German border. Unfortunately, they had to separate when a single family could not be found to take in both women. Mona continued her ruse, but without Wendy to speak for her. And although she was within sight of Holland, she fought the temptation to bolt for home.

Mona found squalid lodgings with a German farm family, and in return helped with farm chores. Blisters on her feet were becoming infected, and she noticed that the child whose bed she had to share was also covered in sores. She was concerned, but there was little she could do.

The Allies were stepping up their attacks on German targets, and soon the occupants of the farmhouse were forced to take cover in the cellar. They remained in their dank refuge for three days, while a rearguard action was waged over their heads. Retreating German soldiers burned anything not destroyed in the fighting at the paranoid order of the Führer, who was convinced that if the Allies prevailed all Germans would suffer. During a lull in fighting, the farmer went above ground to see how the battle was progressing, only to be killed by an artillery shell. When at last the fighting subsided, Mona and the farmer’s widow did not even have a chance to retrieve the farmer’s body for burial before the Polish army came through and advised them to seek refuge in Holland.

Mona could hardly believe her ears—at last she was going back to Holland! She helped the farmer’s widow load a wagon with what few possessions remained, then set out. Once over the border, she dropped her disguise and revealed her identity to a Dutch family who had taken her in. Her Dutch hostess joyfully told Mona of the role Canadians were playing in the liberation of Holland. The next day, outfitted with clothing and shoes given by the family, Mona set out for Laren. The devastated countryside stopped her in her tracks. For years she had imagined freedom and her return home, but she had not imagined the toll exacted on the Dutch countryside by the warring armies. Exhausted and ill, she stopped at a farmhouse near Vlagtwedde. When she told them she was a Canadian trying to return to her home in Laren, the owner’s brother offered to take her to British troops nearby. There, Mona caught her first sight of Canadian battle dress, worn by Clarence Leonard of Halifax.

Mona Parsons Leonhardt, at five foot, eight inches tall, weighed eighty-seven pounds when she stumbled upon her compatriots. They provided food and medical attention. One young soldier gave her a precious gift of three Moirs chocolates sent from home in a care package. Then she was whisked away to Canadian Army Rear Headquarters in Oldenburg, Germany, where she encountered recently promoted Captain Robbins Elliott of the North Nova Scotia Highlanders. Elliott, with Canadian Military Intelligence, was astounded to encounter a woman he knew—his father had been the physician who attended Mona’s mother in her final illness in 1930 —so far away from home. Here was the woman whom his older sister, Shirley Elliott, still remembers in 1998 as a “gorgeous woman, always so well dressed and who loved to dance,” abused but far from defeated. It was in Oldenburg that Mona met up with a childhood friend from Wolfville, Major-General Harry Foster.

By the end of May, Mona Parsons Leonhardt had made it back to her home, via the Canadian General Hospital in Nijmegen. About a month after her return to Laren, she was joined by her husband Willem, who had been liberated from a Nazi prison camp by Americans. (His physical health had severely deteriorated, and he remained a semi-invalid until his death in April 1956. Mona remained by his side, nursing him to the end.)

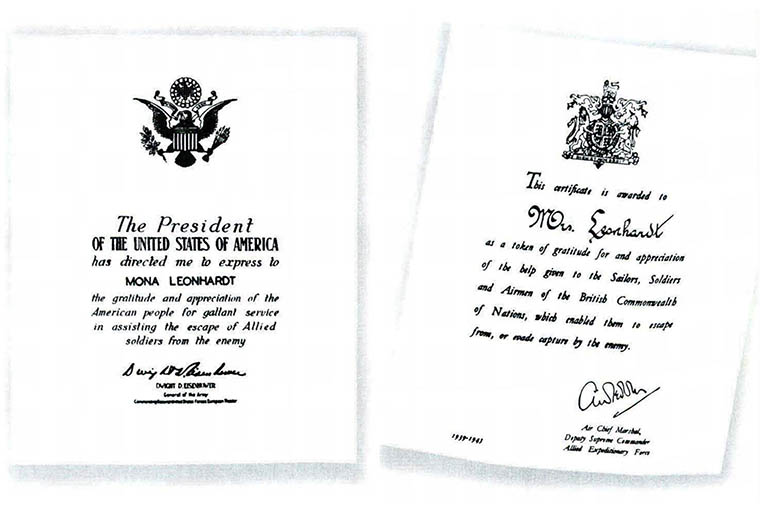

A few months later, Mona was presented with citations from General Eisenhower, commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces, and from Air Chief Marshall Tedder of the Royal Air Force, in gratitude for helping Allied airmen evade enemy capture.

In December 1957, Mona returned to Canada, taking up residence in Halifax. She again met Harry Foster, now widowed and retired from the military. The two married in 1959 and were together until cancer claimed Harry in 1964. Mona moved back to Wolfville, living in quiet retirement in the community where she had spent her youth.

When she told young people stories of her life in German prison camps, they were inclined to think of her as a cultured, refined, but rather senile old dear. After all, what Canadian civilian — and a woman no less — had endured Nazi prison camps?

Plagued by nightmares for the rest of her life, and finally defeated by pneumonia, Mona Parsons Leonhardt Foster died in December 1976. Her possessions, sold at auction, were eagerly scooped up by those who knew the role she had played during the Second World War.

Her story remains largely unknown aside from a mention in the memoirs of a British navigator, and in articles written by Canadian war correspondent Allan Kent in 1945 and herself in 1960. But among the older residents of Wolfville, Nova Scotia, she is remembered with pride and affection.

A stone monument marks the Parsons family plot in a Wolfville cemetery. Mona’s father and mother are remembered on one face of the memorial, her brother Ross, who introduced her to Willem Leonhardt, on another. Her brother Henry Gwynn Parsons is remembered for having donated his body to medical science when he died in 1966. But Mona? Her inscription simply reads

Mona L. Parsons

1901-1976

Wife of Major General Harry Foster

C.B.E., D.S.O.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

More about Mona Parsons

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!