Montréal's Griffintown Reborn

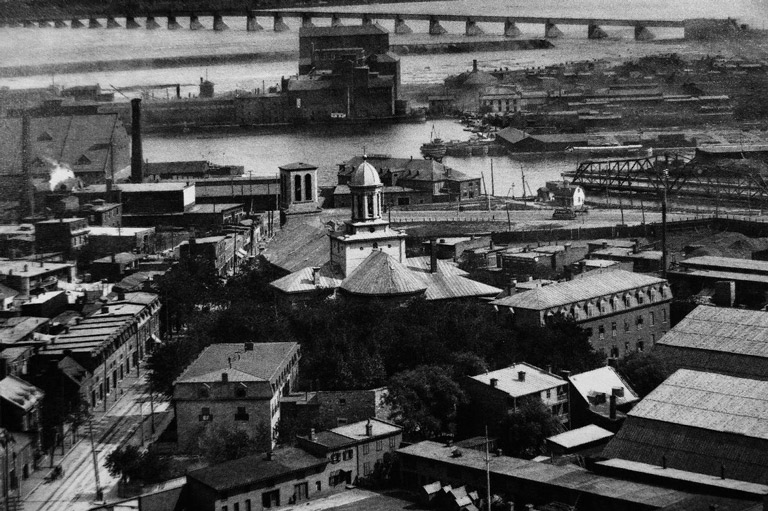

Located just a kilometre or so southeast of the skyscrapers of downtown Montréal, the sixty-seven-hectare area known as Griffintown once served as the crucible of the Industrial Revolution in Canada. Here, more than a century and a half ago, factories sprang up along a canal that circumvented the same Lachine Rapids that had stopped early French explorer Jacques Cartier in his search for the Northwest Passage to China.

During its heyday in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Griff, as some locals call it, was home to a hardscrabble community of dirt-poor workers. Decades later, wracked by social and economic changes, it turned into a virtual ghost town before being reborn at the dawn of the twenty-first century as a new home for upscale urban dwellers. Today they populate a mushrooming collection of condo towers that stand within walking distance of recently opened trendy bars, cafés, and restaurants.

When the fortifications that encompassed Old Montréal finally came down in the early 1800s, the area to the southwest, once a seigneurial property, was well placed for development as the city’s first suburb. Irish merchant Thomas McCord had already obtained a ninety-year lease on the land. But after McCord returned to Ireland to deal with business issues, an unscrupulous associate sold the land illegally to Mary Griffin. She subdivided the area, laid out the first roads, and built low-cost housing.

McCord eventually received compensation after a protracted legal battle, but the name Griffintown stuck.

Many of its earliest residents helped to build the Lachine Canal. Opened in 1825, the mammoth project provided work for an ever-increasing influx of mostly Irish immigrants. That turned into a flood after the potato famine of the 1840s forced a half million Irish to seek a better life in North America. The new inhabitants of Griffintown helped to widen and deepen the Lachine Canal, making it suitable for bigger ships that could transport the products from the flour mills, foundries, breweries, sawmills, and textile factories that clustered along the waterway.

The area remained predominately Irish well into the twentieth century, when fortunes started to wane, first with the Great Depression and later when the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959 made the canal obsolete for commercial traffic.

Fortunately for visitors today, one strip remains of the nineteenth century brick row houses that once served as homes for some of the residents. On the north side of de la Montagne stands a section of red brick townhouses built in the early 1880s.

The houses feature mansard roofs, dormers, and a porte cochère: an opening to allow horse-drawn carts to reach the backyard. Conditions in these homes were bleak — crowded, poorly heated, and a breeding ground for bacteria. In 1846–47, six thousand people from Griffintown and the area just south of the Lachine Canal died from typhus and were buried in a common grave marked by a three-metre high engraved stone near the Victoria Bridge.

In 1852, a fire destroyed half the town. Flooding from the nearby St. Lawrence River caused regular inundations that buried streets under several feet of water.

Very few of the factories from the neighbourhood survive. The oldest one is the New City Gas Company at the corner of Dalhousie and Ottawa. It was built in 1859 of brick and limestone and was used originally to burn coke to produce the gas that lit the streets of Montréal at the time. The building features an iconic roof and walls punctuated by elegantly simple buttresses. One of the designers who worked on the original structure was John Ostell, responsible for the 1837 Arts Building at McGill University, one of Montréal’s most recognizable landmarks.

Two blocks southwest, an RAF Liberator bomber crashed on a flight to England in 1944, killing fifteen people. Also nearby is the Griffintown Horse Palace. There have been stables here since the 1860s, and today they are used to board horses that haul tourist-laden calèches through Old Montréal.

No trip to Griffintown would be complete without a visit to the Lachine Canal, where recreation, not commerce, is now the draw. A paved path next to the canal, extending twelve kilometres from Old Montréal through Griffintown to Lachine in the west, is a popular spot for visitors. The locks were restored in the 1990s and opened to pleasure boaters in 2002. Along the banks of the canal you can still spot the occasional bollard: black, mushroom-shaped mooring posts that were once used to tie up ships.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Help support history teachers across Canada!

By donating your unused Aeroplan points to Canada’s History Society, you help us provide teachers with resources to engage students in learning about the past.