The Fire Horses

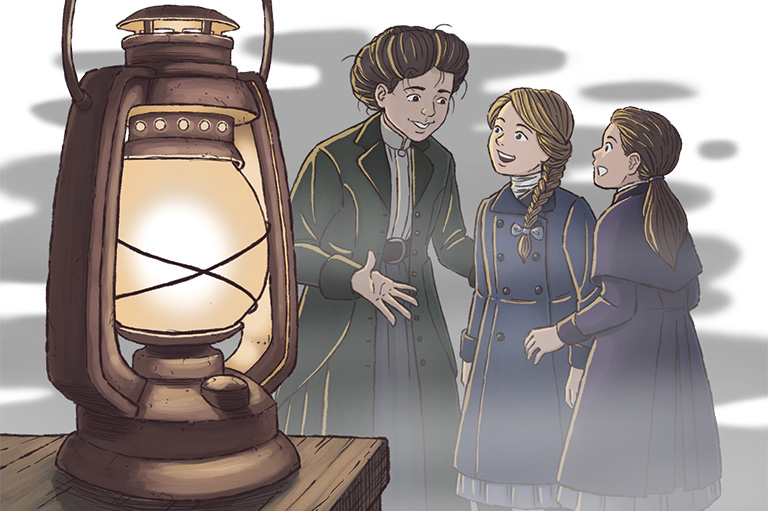

Guests of the Manitoba Hotel pressed back as a soot-covered madman led Frank — a frothing, smoke-stained horse with a yapping dog at his heels — through the foyer and up to the bar. The guests stared in amazement as the man ordered a whisky for himself and a beer for his horse. When the strange and smelly entourage finally left, the onlookers sighed with relief.

The madman was none other than Chief William McRobie of the newly reformed Winnipeg Fire Department, enjoying his customary after-fire refreshment. It is not known if Frank the horse slurped his beer straight off the bar or drank it out of a bucket. But it is known that one New Year’s Day, when McRobie left him untied at the side of the road to attend a house party, Frank trotted off, apparently headed to the city for his “little nip.”

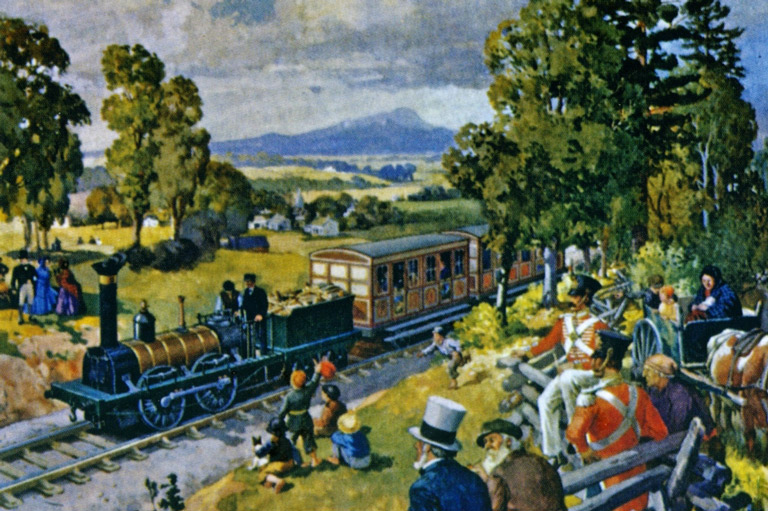

In the days before automotive engines, firefighters forged strong bonds with their horses. McRobie, who became Winnipeg’s first professional fire chief in 1882, was no exception. When the alarm went off, he was known to ride Frank bareback, at breakneck speed, while blowing his bugle to warn people to get out of the way.

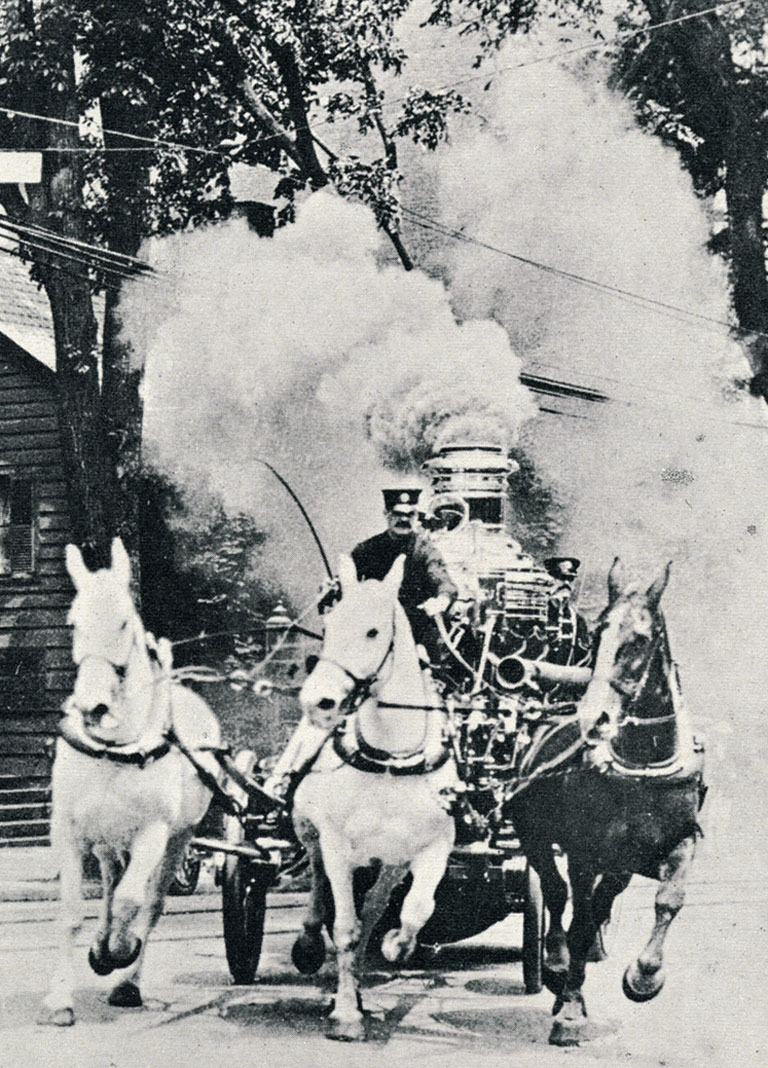

Fire horses were a common sight in most Canadian cities from about the mid-1800s to as late as the 1930s. They were usually kept in stables at the rear of the fire hall. When the alarm went off, the well-trained horses would move to their places in front of the rigs. Harnesses suspended from the ceiling were lowered and attached, allowing for a fast exit.

The magnificent horses — some weighing close to 700 kilograms — ran through the streets pulling steam-powered pumpers. Stories of their loyalty, bravery, and intelligence lived long after they were replaced with motor engines.

Grey Dick was one such horse of legend.

Grey Dick was purchased by the Winnipeg Fire Department on April 5, 1886, when he was five years old. A relative lightweight of less than 500 kilograms, Dick was not big enough to pull any of the wagons with his much larger stablemates. But he gained fame as the faithful buggy horse for three successive fire chiefs.

After ten years on the job, Grey Dick was dispatched to a downtown fire on a muggy night in 1896. He was tied in front of a building that was enveloped in heavy smoke. After a sympathetic onlooker set him free, Dick panicked and disappeared into the night. In the mad dash that followed, he fell into a freshly dug sewer hole in front of city hall and badly tore his tendon. It appeared Dick’s days were numbered.

When a search party found him, no effort was spared to save his life. Firefighters scrambled into the hole and fitted bellybands around his body. Workers then placed a derrick over the hole and hoisted the animal out. He was rushed to the veterinary hospital, where he was suspended in the air as vets worked on his leg. Fortunately, just enough tendon remained to start the healing process. After six months, Grey Dick was fit enough to return to duty. He attended fires for another ten years.

Fredericton, New Brunswick, which was the last Canadian city to retire its fire horses in 1938, made much of its favourite, Old Bill. A 1938 obituary in the Daily Mail described him as a “snow-white smoke-eater ” who was the “last fire horse of the Dominon.” For many years his hoofprints were on display in a new section of cement sidewalk in front of the city's downtown fire station.

The roadways of early twentieth-century cities were not kind to horses. They hauled at full speed over mud, rutted clay, ice, and heavy snow. Rubber boots and hoof chains were tried with minimal success.

Fire hall records also tell of ailments such as front leg bone splints, cuts and gashes, sprains, colds, declining body condition, disease, and emotional difficulties. Any horse unable to return to duty was usually sold, taken to auction, or turned out to pasture.

The horses were generally well cared for. Stalls were mucked out every day. The horses were served the best hay and oats, and groomed and walked daily.

Winnipeg’s 1936 winter dumped a huge amount of snow. The new automotive trucks were left spinning their wheels until someone remembered the horses.

Sometimes, though, men had to bunk in uncomfortably close proximity to the animals. A constable in St. John’s, Newfoundland, complained in the early 1930s of having to sleep above the fire hall stable: “We slept there with the stink of that. We didn’t have cots, we had bunks built up on the side of the wall. The hay was stored in another part of it there, and the fleas would get in the hay. There was fleas, and you name it. It was never as bad as that out to the seal fishery in my time,” said the constable, who was quoted in a report by the Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador.

But all was not hard work and danger. There were many days of quiet leisure. Sparkling red fire-wagons and bathed and brushed horses took part in parades.

Horses lent a certain romance to firefighting, but their glory days ended with the coming of the motorized pumper. An April 1928 Winnipeg newspaper article lamented the end of an era: “Four of Winnipeg’s fast-disappearing equine firefighters — crowded out of their once enviable jobs by the high-pressure competition of the motor truck...Horses will soon disappear altogether from the city’s fire department.”

By the early 1930s, horses were phased out in most cities. The retired horses were sold or given away. Some went to farms, others went to work pulling milk wagons or bread carts. Old habits died hard, though. In Saskatoon, there were reports of former fire horses jumping into action after hearing a fire alarm, with milk bottles bouncing around inside the wagon they were pulling and no driver on board.

And as though to provide one last hurrah, Winnipeg’s 1936 winter dumped a huge amount of snow. The new automotive trucks were left spinning their wheels until someone remembered the horses.

A few old faithfuls were brought out of retirement and, in one final glorious moment, proudly pulled the vehicles through otherwise impassable streets.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!