Dreaming of Eden in the New Brunswick Bush

In 1864, two poor New Brunswick intellectuals, Joel Bonney Craig and his wife Sarah Jamieson Craig, launched their plan to organize a “colony of true, Christian dress and health reformers,” a self-sufficient communal farm run along strict principles of “progressive health reform.”

In an article published in the January 1864 issue of The Herald of Health, a New York alternative-health magazine, Joel described their ideal community as a place.

“where we may “worship God in our bodies as well as our spirits,” free from the frowns, persecutions, and evil influences of fashionable society; where those who wish to reform their habits of life, but have not strength and resistance sufficient to overcome the opposition of those by whom they are now surrounded, may find a home in which they can grow and enjoy the company and counsel of pure and congenial spirits; where profanity, licentiousness, and quarrelling shall not be tolerated, and where the manufacture, sale, and use of all alcoholic and drug medicines shall be forever prohibited (except perhaps in some rare surgical cases); where foul tobacco shall not be allowed in any form, and where innocent animals shall not be abused, killed, and devoured by human beings as in other places.”

He goes on to describe a community in which the sexes would be equal, with boys and girls educated together. Those interested in joining such a colony were urged to write to J.B. Craig, president of the Universal Progressive Reform Association, the local health reform club organized by the Craigs in 1861.

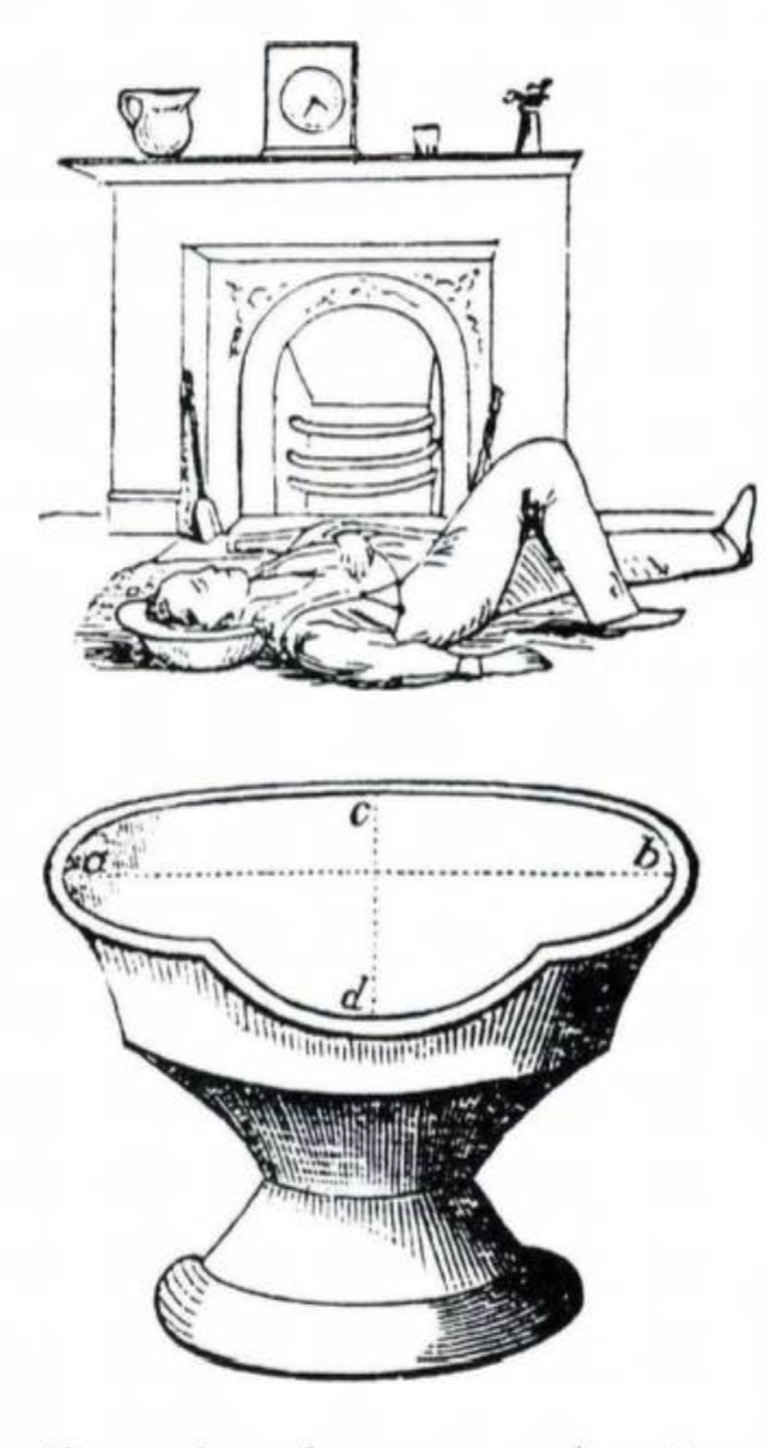

Sarah and Joel had been reading alternative-health magazines since before their marriage in 1860, and were particularly interested in the “water cure” or “hydropathy.”

This interest had much to do with a knee wound Joel received in his youth that healed badly due to improper cleansing. The injury had left him partly crippled and unable to do the types of heavy work that were necessary to make a decent living in the sparsely settled communities of Whittier’s Ridge, Clarence Hill, and Rolling Dam north of St. Andrews, New Brunswick.

As it was, his physical disability kept him and his family desperately poor. Fuelled by frustration at their poverty and by the fiery rhetoric of the American health-reform movement, the Craigs’ interest in hydropathy had by the mid-1860s warmed to an evangelical fervour.

Hydropathy was an alternative medical system that enjoyed great popularity in the United States from the 1840s to the 1860s. Central to the hydropathic philosophy was the belief in the body’s ability to heal itself, and advocates preached the efficacy of clean water, applied both externally and internally, in curing diseases of all kinds.

First popularized by the Austrian peasant Vincent Priessnitz in early nineteenth-century Graefenberg, the water-cure movement spread to the U.S. in the 1840s.

Two of the founders of the American movement, Joel Shew and Russell Thatcher Trail, opened a water-cure house in New York in 1843 where they put Priessnitz’s methods into practice. There they expanded their system’s narrow focus on water as a healing agent to include the prevention of illness through proper diet, exercise, and dress (especially for women).

Within a few years, the movement was advocating a whole range of lifestyle changes in the name of better health. The system’s main publication, The Water Cure Journal (later renamed The Herald of Health), encouraged the practice of health reform at home, and by the 1850s had thousands of subscribers across North America.

Hydropathy flourished in reaction to the shortcomings of conventional nineteenth-century medical practitioners, most of whom relied on interventionist methods (such as bleeding and blistering) and alcohol- based drugs.

Water-cure converts railed at the methods of the “drug doctors” who “poisoned” their patients with alcohol and calomel (a mercury chloride compound traditionally used as a purgative). They also raged against the fashionable corsets and long, heavy dresses that were so damaging to women’s health.

As the movement gained popularity, the high-fat, high-salt, and high-sugar diet of many North Americans also became a target of hydropathists’ wrath.

The claim that water could be used to treat all diseases seems preposterous today. Yet it was not until the late nineteenth century that the “germ theory” of disease became at all accepted in medical circles. Indeed, even by the 1840s, little real progress had been made since the Middle Ages in the understanding of disease and its transmission.

Certainly, the hydropathic healers were working from a model of human physiology as limited as that recognized by regular doctors, but at least their emphasis on bathing and proper diet did no harm. In fact, it likely improved the general health of their patients, even in cases where it could not completely cure them.

Sarah and Joel were clearly unusual in their interest in alternative medicine, at least in the context of their remote neighbourhood north of St. Andrews. Yet both had long been regarded as eccentrics in the community.

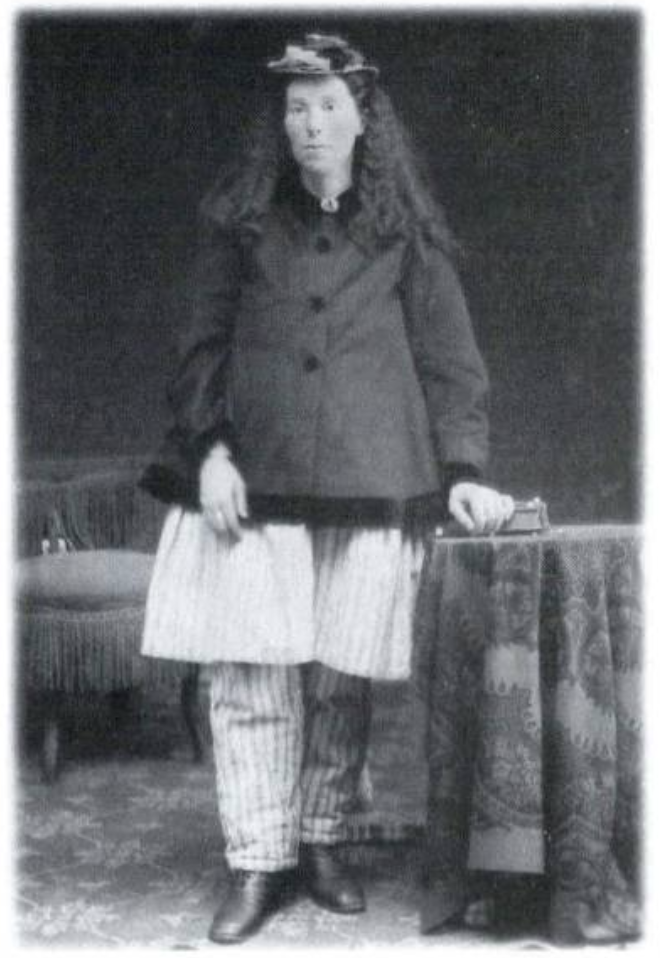

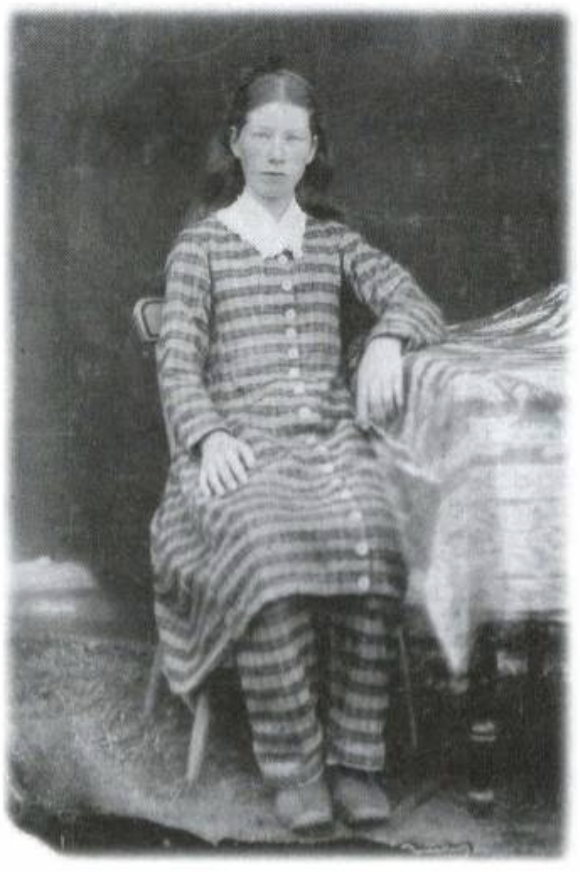

Sarah had been a dress reformer since 1857, when she made and wore her first “American Costume” (a knee-length, uncorseted dress worn over long pants) at the age of 17. She continued to wear this outfit even on her wedding day and claimed to have been ridiculed for it by many members of the community.

This, coupled with her strident views on diet and medication, did little to endear her to her neighbours. As for Joel, his disability had marked him since adolescence as “different,” and in an area where most men worked “away” from home for part of the year, lumbering or fishing or labouring in the shipyards, many regarded Joel’s inability to work “away” as mere laziness.

All of these factors contributed to the Craigs’ feelings of dislocation from their community. Sarah’s diaries and memoirs reveal an intense sense of isolation:

“The people among whom we lived were mostly slow, ignorant, stolid; living in a rut; never thinking (or if told never believing) there was any other or better way to live. Many were intensely low-lived, vulgar, and profane. … We had scarcely one congenial spirit, with whom we could talk face to face.”

In the absence of all but a handful of sympathetic friends, Sarah and Joel found their “community” elsewhere, in the pages of American health-reform magazines. Despite their extreme poverty, they managed to subscribe to The Herald of Health and The Laws of Life, a journal published at the water-cure establishment Our Home on the Hillside in Dansville, New York — sometimes by selling subscriptions to these magazines themselves.

In 1862 Sarah’s brother Albert came home to die from consumption, but was “cured” by the hydropathic treatment administered by Sarah and her mother. His miraculous recovery certainly impressed the community, but it did little to reconcile the people to Sarah and Joel’s radical attitudes about diet (no salt, alcohol, tea, coffee, or meat) and their practice of hydropathy.

Indeed, in a letter to The Herald of Health in August 1864, Sarah described her treatment of four patients and the hostile reactions of the community. In the case of one pregnant woman who collapsed on the road, Sarah wrote of her imposition of a strict diet of “fresh oatmeal gruel, apples, oranges, raisins, … and Graham bread when she could take it” in the face of strong opposition from the woman’s family.

The “meat, fine bread, and draughts of gin” that her relatives advocated were apparently the types of foods deemed appropriate for the sick by the community, yet this was precisely the diet deplored by the health reform movement. Sarah commented triumphantly that “they only managed to give her salted gruel twice when we were not on hand.”

Nevertheless, this incident apparently provoked much anger among the woman’s relatives and neighbours. Sarah’s account may well be exaggerated, but it offers a glimpse of the community’s reaction to her methods:

“The most scandalous falsehoods about “starving!” “freezing,” “drowning,” etc., were circulated for miles around. Her father came and “raised a breeze” about her food and treatment; but neither threats, persuasion, ridicule, nor the grossest misrepresentation could move us from our allegiance to the better way.”

Whether or not the community was as hostile as she said, Sarah’s perception of this hostility was clear. In such a context, the idea of a close community of kindred spirits, far from the derisive eyes of such ignorant neighbours, must have seemed akin to paradise.

The call for a “colony of reformers” in The Herald of Health brought a deluge of correspondence from eager health and dress reformers all across North America. Letters came from as far away as California. Sarah and Joel had to add secretarial duties to their daily struggle for survival. As Sarah wrote in her memoir:

“All our spare time and much of our sleeping time was spent writing and answering letters. Forwarding and receiving our mail through Calais post office, we used the U.S. 3-cent stamps, which were freely furnished by our correspondents … When our neighbours went to town they usually crossed the river and by them we sent our letters — often 12 to 16 at a time — and a line to the Postmaster would bring our mail back.”

The amount of correspondence soon became burdensome; Sarah was answering letters with her month-old baby on her lap. To a large extent, each correspondent required the same basic information, written over and over again.

A small printing press would, Sarah and Joel imagined, solve this problem by allowing them to print leaflets and perhaps even a “tiny periodical.” They wrote to their correspondents, who immediately began sending small amounts of money for a press — from 25 cents to a dollar each.

Some of the type they acquired at no cost when raiders attacked the St. Croix Herald at night and threw the presses into the river, where Joel and Sarah’s brother, Isaac, found them and salvaged the type early the next morning. When at last they had saved enough money to buy the press they wanted, disappointment set in.

The press would print only the first page and part of the last. Nevertheless, in October 1864, they printed off the first and only number of their paper, The Car of Progress, and mailed it out.

Each of the prospective colonists had his or her own idea of which region would best meet the criteria for the colony’s success as a self-sufficient community. In Joel’s initial article, he had expressed the hope of being able to take advantage of the Homestead Law in the western U.S. This, however, proved impossible. Instead, land agents wrote only of properties for sale at prices well beyond those the correspondents could afford.

Sarah and Joel’s project was only one of many utopian schemes planned and established in the nineteenth century. However, most of the others had either a charismatic personality or a rich benefactor (or both) behind them.

Sarah and Joel were apparently naive enough to believe that, poor as they were, they could launch such a scheme on their own. They had received most of their education at home, but read widely and voraciously from an early age. They were so articulate in print that their correspondents could be forgiven for mistaking them for people of some education and resources. Such was not the case.

Indeed, in her memoirs Sarah described their “home affairs” as very grim during the time of their colony scheme. They tried to farm their land, but the neighbours’ cows always managed to trample the crops because “one lame man” (Joel) could not keep the property properly fenced. She wrote:

“Though we farmed all we could each season, we never could raise half a crop. Some falls we housed vegetables, beans and peas enough to last through winter and plant next spring, but often not. In spring how carefully we cut the potatoes to get all the eyes to plant, yet leave a piece for the pot!”

The Craigs’ plans were always frustrated by a lack of resources. When they finally chose southeast Kansas as the best location for what they called “our Eden,” low land prices in New Brunswick prevented them from joining their fellow reformers.

Many of their correspondents had land that they could sell at a fair price, but Sarah and Joel’s property was worth little.

Sarah noted, “Our place — would bring but a small price, if it sold at all. We could not go unless we sold.” The Craigs continued their correspondence, urging the others to move ahead with the colony plan in the hope that they themselves would one day be able to join them.

A disastrous house fire on January 29, 1865, put a final end to their hopes of relocating. While Sarah and her sick baby were staying at her parents’ home and Joel was out, the house caught fire and burned to the ground. Sarah’s diary entry captures her desolation:

“Not only our poor, barn-like house is gone, with our clothing, bedding, furniture, provisions … but our noble and valuable library of books, magazines and periodicals, — volumes of History, Biography, Travels, Science, literature, art etc., for which with our piles of manuscripts and correspondence, we would not have taken any money, and which no money can restore — all, all “swept to oblivion by one fell stroke of the relentless destroyer.”

Left destitute, Joel and Sarah were forced to focus all their attention on their own survival.

Sarah wrote to The Herald of Health to inform correspondents whose addresses had been lost in the fire. Her brave rhetoric and apparent determination masked what must have been a desperate situation at home:

“Our friends probably think we have grown lukewarm in the cause, and given up the “Colony” enterprise for want of means to carry it out. We wish to assure our friends that our zeal has not one whit abated, nor our determination grown weaker to seek and find a congenial home for ourselves, and all who can join hand, heart and soul with us — where we shall be wholly free from the trammels of society and fashionable life-free to live, and grow back into the arms of Mother Nature,and make our home an Eden! Though obstacles have seemed to thicken in our path, we confidently trust in God, firmly believing that He will aid all who earnestly labor for the establishment of His kingdom on earth.”

Responses began to arrive in the mail. Some would-be colonists sent small amounts of money for the relief of the family. Others who were able to sell their land moved to Kansas in the hope that their friends would follow. But Sarah lamented that even among those who went to Kansas, many “nearly always gravitated to where paying work could be had, to await further developments.”

Without the Craigs’ enthusiastic leadership, the colony never cohered. As late as September 1866, Sarah and Joel were still trying to procure lands in Kansas, but with their failure to do so, the colony scheme finally collapsed.

A postscript to the utopian plan occurred a few months after Joel’s death in 1886. Hearing of Sarah’s widowhood and her need to find a new home for herself and her children, one of the old correspondents, James Allen, wrote to offer them a place in New Jersey.

He and his wife were travelling and lecturing on health issues, and needed someone to farm their land for them. Sarah’s enthusiasm is evident in her diary entry:

“He wants his place taken care of while he is away; and he wants to get a number of progressive people together to form the nucleus of a co-operative or Communistic Home, somewhat on the plan suggested by my husband and me over twenty years ago. How delightful if the seed we two then planted should bear goodfruit, and I and my children live to pluck it.”

This idealistic plan also failed. Upon arriving in New Jersey in January 1888, Sarah found that the Allen farm was too small and in no condition to support her and her children. Once again, poverty frustrated her plans.

Mrs. Allen offered the family all they could raise on the property, but with no money to buy manure and seed, or to live on until the harvest, Sarah was forced to admit that the project was doomed.

A more cynical assessment of the New Jersey episode can be found in a letter from Sarah’s brother Edwin to Sarah’s youngest daughter Florence in 1935.

Edwin had grown up during the first excitement of the colony scheme, and at the age of nine had helped Joel set the type in the printing press for The Car of Progress. Yet his outsider’s eye allowed him to see the follies of the New Jersey venture more clearly than his determined sister ever could.

He wrote to Florence: “Your mother was assured by the Allens and others that the whole family could easily earn a livelihood by picking fruit! What sort of fruit could be picked in winter was not specified.”

Edwin then pointed out that nearly all of the utopian schemes of the nineteenth century soon broke apart due to the “incompatibility” of their members. Here he pinpointed an issue that neither Sarah nor Joel seems ever to have considered.

What if they had been able to sell their land and “plant their colony” in Kansas with this group of people whom they had never met? Could such a collection of diverse personalities ever have cohered as a community? If Sarah’s dealings with the Allens in New Jersey afforded any hints, the likelihood of failure was enormous.

Nevertheless, Sarah Craig’s own assessment of the colony project, which appeared years later in her memoir, revealed its true significance in her life:

“Though our colony was never settled, and the scheme may be said to have come to naught, it was not without bearing fruit. We gained much useful knowledge; and the intercourse, even by correspondence, with intelligent, progressive minds, was both cheering and helpful; and truly a means of much mental and spiritual uplift — worth tenfold more than it cost us!”

This in fact offers a glimpse of the true power of the utopian scheme. The dream of creating their own Eden gave Sarah and Joel a gleam of hope in the midst of the bleakest poverty, isolated lives filled with failed business deals, recurrent illness and unemployment, crop failures, and the deaths of beloved children.

The dream of a better life in an ideal community made their struggle in the New Brunswick bush bearable.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!