Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Titans

We asked noted business historian and Canada’s History Society President Emeritus Joseph E. Martin to select ten leading entrepreneurs from this country’s past. Martin focused on people who made their greatest impact within Canada and on those who died before the year 2000, presenting his selections in the order of their years of death.

These individuals were involved in a great diversity of enterprises, from the fur trade to brewing and distilling; railways, agricultural equipment, and automobiles; forestry and oil; and, of course, banking and finance. Eight of the businesspeople Martin profiled have been inducted into the Canadian Business Hall of Fame.

Article continues below photo gallery.

-

Molson's Brewery beer cart, Montréal, circa 1908.McCord Museum

Molson's Brewery beer cart, Montréal, circa 1908.McCord Museum -

Donald A. Smith drives the "last spike" at Craigellachie, British Columbia, November 1855.Library and Archives Canada

Donald A. Smith drives the "last spike" at Craigellachie, British Columbia, November 1855.Library and Archives Canada -

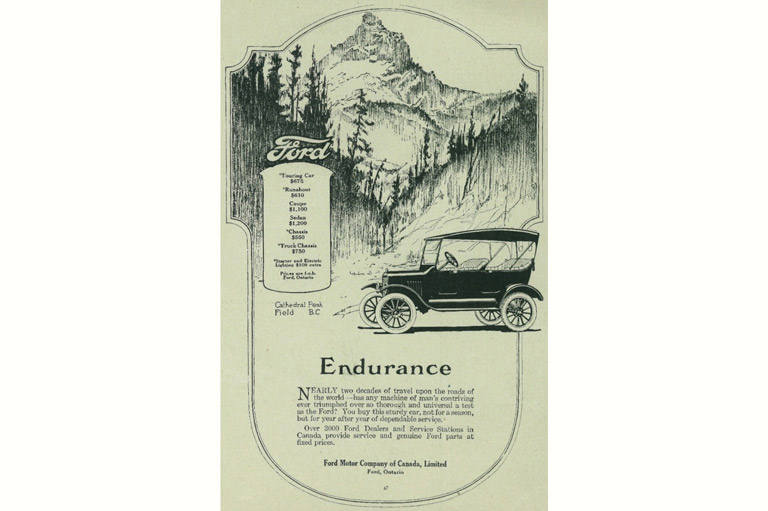

An advertisement for the Ford Motor Company of Canada promotes Ford's "sturdy" and "dependable" automobiles.

An advertisement for the Ford Motor Company of Canada promotes Ford's "sturdy" and "dependable" automobiles. -

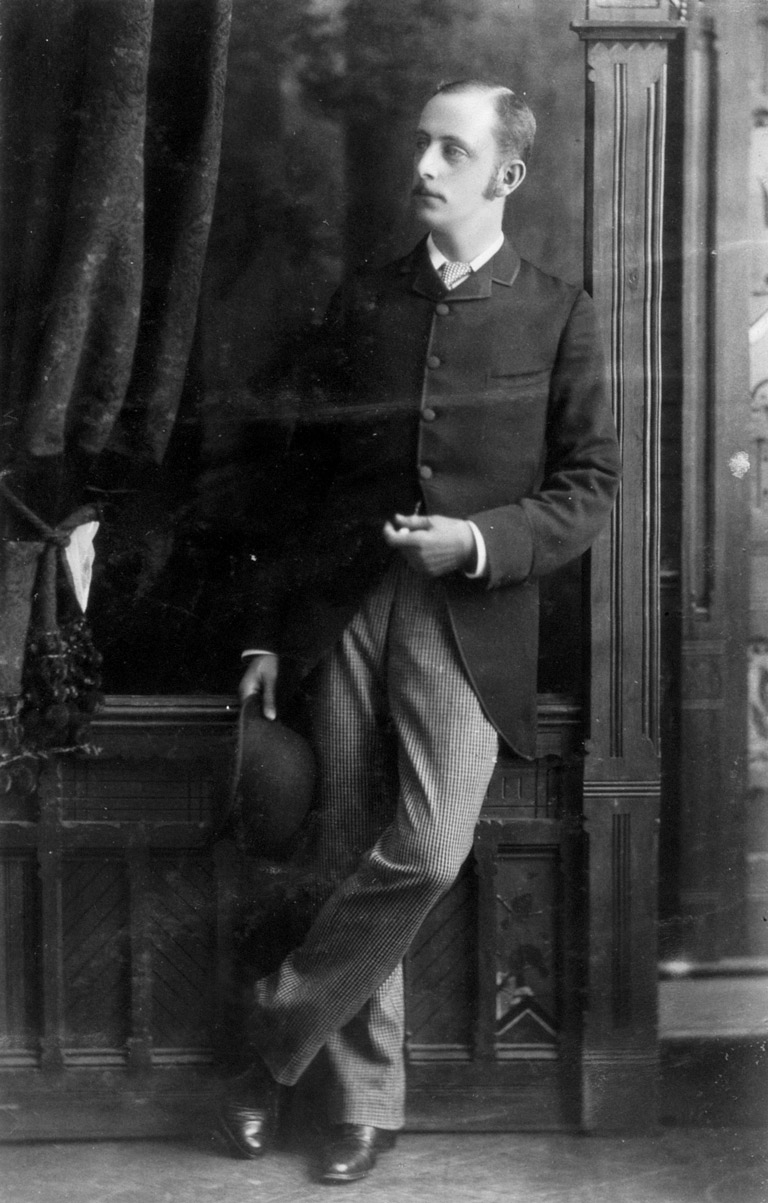

Timothy Eaton, left, speaks to his son John Craig Eaton at their Eaton's department store in Toronto, circa 1899.

Timothy Eaton, left, speaks to his son John Craig Eaton at their Eaton's department store in Toronto, circa 1899. -

An advertisement for Seagram's V.O Canadian Whisky.

An advertisement for Seagram's V.O Canadian Whisky. -

A truck at Campbell River, British Columbia, hauls logs for MacMillian Bloedel, date unknown.Museum at Campbell River

A truck at Campbell River, British Columbia, hauls logs for MacMillian Bloedel, date unknown.Museum at Campbell River -

An Irving gas station in St. John's Newfoundland.Flickr / Elijah van der Giessen

An Irving gas station in St. John's Newfoundland.Flickr / Elijah van der Giessen

The Brewing Baron

John Molson (1763–1836)

The leaders of the business establishment in late-eighteenth-century Montreal were Scots, and their main business was the fur trade. It is thus somewhat ironic that the first person mentioned here is an Englishman, not a Scot. John Molson was born in Lincolnshire, England, in 1763. He immigrated to Montreal when he was just nineteen years old. He lived the rest of his life in Lower Canada, dying in 1836, although he visited England more than once.

Four years after landing in Canada, Molson started a brewery whose name survives to this day as part of the Molson Coors Brewing Company. He had a tremendous interest in innovation, and, as historian Alfred Dubuc has written, “brewing was at the forefront of technological innovation … during the late-eighteenth century.” Molson convinced Canadian farmers to grow more barley. While barley was first grown in New France in the 1600s, when British settlers arrived in the 1760s, they brought with them two-row barley varieties considered ideal for British-style ales.

At the time, the population was growing rapidly as a result of immigrants arriving from the U.S. and Britain. Brewing proved to be a highly successful business, but Molson also diversified into other innovative fields — first steamships and then railways. In 1809, two years after American inventor Robert Fulton launched the first commercial steamboat — the Clermont — on the Hudson River, Molson and two partners sailed the steam-driven paddlewheeler Accommodation from Montreal to Quebec. The Canadian-built vessel was the first steamboat to be manufactured entirely in North America.

Molson’s initial investment led to the creation of the St. Lawrence Steamboat Company, popularly known as the Molson Line. By the 1830s he was also the largest shareholder in Canada’s first railway — the Champlain and St. Lawrence Railroad.

Molson was president of the Bank of Montreal from 1826 to 1830, a time when the bank was at an important crossroads and needed new direction. Fittingly, Montreal’s Concordia University named its business school after Molson — the greatest entrepreneur of his day and someone who was dedicated to continuous innovation.

The Farm Machinery Mogul

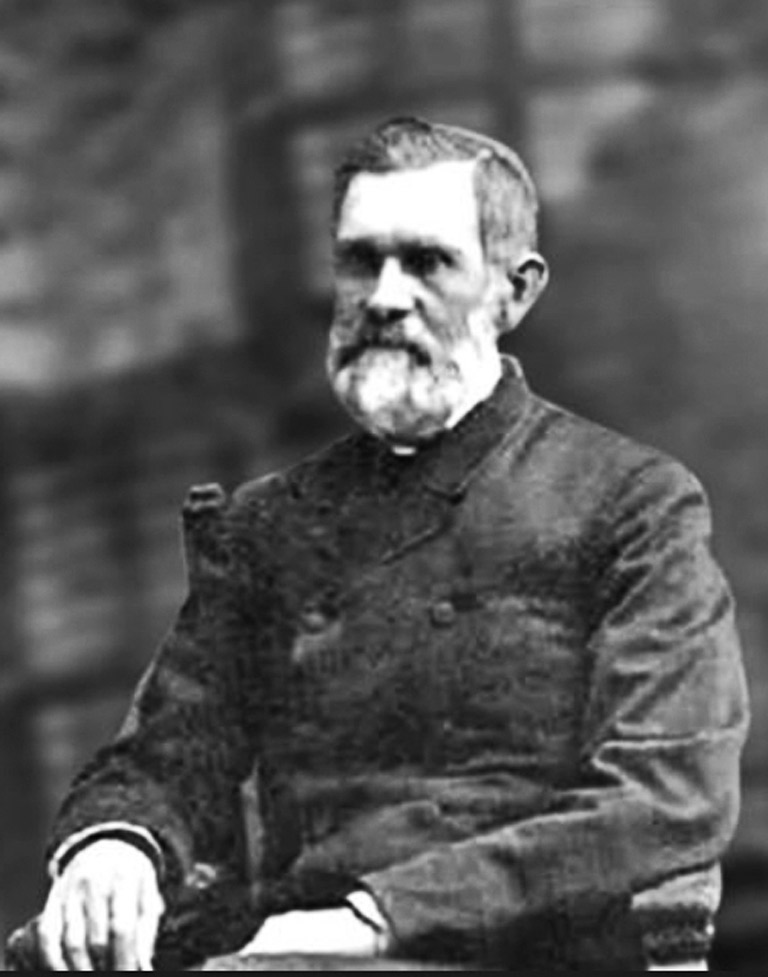

Hart Massey (1823–1896)

Hart Massey was born in Northumberland County, Upper Canada, in the early nineteenth century, married in New York State mid-century, and died in Toronto in the late-nineteenth century. Massey’s parents and wife were Americans. He received part of his education in the United States, lived for a decade in Cleveland, and held both American and Canadian citizenship.

Massey is best known for building the largest agricultural machinery company in the British Empire. In 1851, he joined his father’s manufacturing business in Newcastle, Canada West (Ontario), and he took charge upon his father’s death in 1856. Massey was well aware of the technological changes going on in the United States and obtained rights to manufacture mowers, reapers, and other products in Canada.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the farm equipment making industry was highly fragmented in both countries. Besides being an excellent marketer and manager, Massey demonstrated how to survive in a rapidly consolidating industry. In the late 1870s, he moved the company’s headquarters to Toronto, where a huge new factory — then the largest of its kind in the British Empire — was built.

As early as 1867, Massey was interested in new markets, beginning in Europe and shortly thereafter looking at Western Canada, which was just beginning to open up. However, he preferred international markets to those of the Canadian West and expanded to Argentina and Australia, as well as to Europe in the 1880s.

His son Charles was expected to succeed him, but when Charles died suddenly of typhoid in 1884, Hart returned to management and executed consolidating mergers, first with the Harris firm — after which the company was renamed Massey-Harris — and then with Patterson-Wisner Co. After the latter merger, Massey-Harris was a full-line implement maker with sixty per cent of the Canadian market.

Massey benefited from a protective tariff, even though he was often critical of certain parts of it. Before his death, he wanted to enter the U.S. market.

The Massey name lives on in tractor sales around the world and at three important Toronto institutions: the Massey Hall performance venue, as well as Hart House and Massey College, both at the University of Toronto.

The fur trader and train tycoon

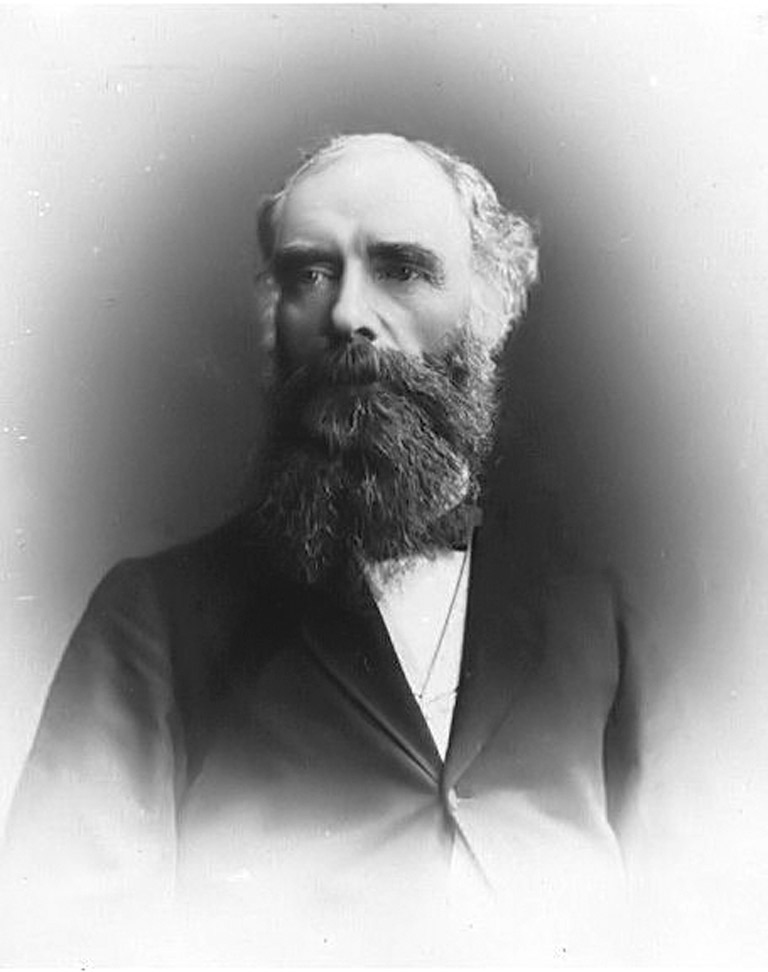

Sir Donald Alexander Smith, 1st Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal (1820–1914)

Donald Alexander Smith was born in Forres, Scotland, in 1820. In 1838, as an employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), he came to Labrador, where he spent the first thirty years of his business life. Smith began to invest money for his fellow employees, and he climbed the corporate ladder to become chief factor of Labrador — hence his nickname “Labrador” Smith.

In 1868, he transferred to Montreal, where he lived until 1896, apart from a brief period in the Red River Settlement. In Montreal he was the HBC’s commissioner of eastern operations. By then a wealthy man with a prestigious position, he began to invest in major manufacturers of textiles and rolling stock.

In late 1869, Smith went west to the Red River Settlement to help to deal with Métis concerns about the sale of Rupert’s Land to Canada. He negotiated with Louis Riel, became involved in politics, and met railway executive James J. Hill. Together they discussed building a transcontinental Canadian railway.

In 1872, Smith was appointed to the board of the Bank of Montreal. But his big play, acting with other investors, was purchasing the Saint Paul and Pacific Railroad, which later bought the Great Northern Railway. In 1879, he resigned as land commissioner for the HBC; but he later returned to the company as principal shareholder and governor, a position he held for a quarter century.

Smith was one of the unshakable investors in the Canadian Pacific Railway and the man who drove the last spike — as portrayed in the most famous Canadian business photograph.

Although he was disappointed that he did not succeed his cousin, George Stephen, as president of Canadian Pacific, he did succeed him as president of the Bank of Montreal and served in that role for nearly two decades.

Smith was involved in an extraordinary range of investments in Montreal and in Manitoba, but his largest investments were in two American railways. And at age eighty-nine he became the first chairman of the board of what became British Petroleum. Knighted in 1886, he became the first Baron of Strathcona and Mount Royal in 1897. Historian Alexander Reford has described Smith as the “foremost example of rags to riches in a Canadian context.” He died in London, England, in 1914.

The people's banker

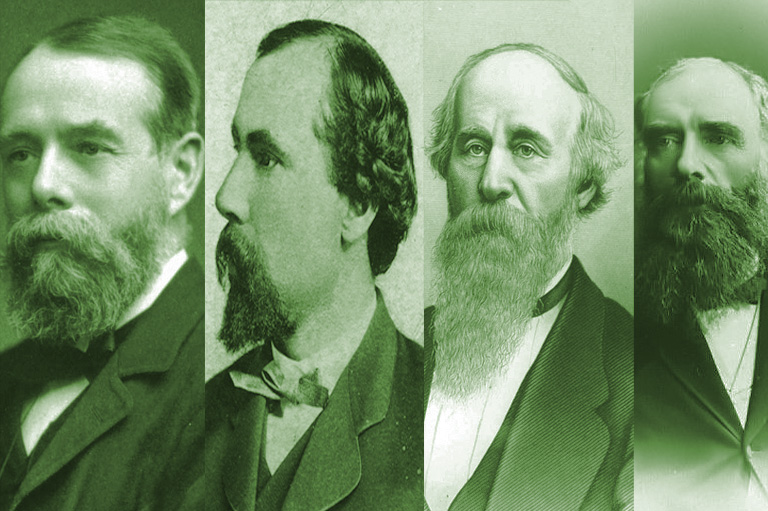

Alphonse Desjardins (1854–1920)

Alphonse Desjardins was born in Lévis, Canada East, in 1854 and died there in 1920. He never moved far from home but had an enormous influence upon his region, province, and country, as well as the northeastern United States.

A journalist by profession, Desjardins was also an active political Conservative. He was appointed the recorder of debates in the Quebec legislative assembly and, later, the French-language stenographer for the House of Commons.

Desjardins became concerned about the inability of Quebec farmers and small businesses to obtain capital at other-than-usurious rates, and he came across the work of British author Henry William Wolff, who was president of the International Co-operative Alliance. Desjardins contacted Wolff and others in Europe, eventually becoming a staunch supporter of the co-operative concept. He saw it as an ideal method for fighting the ridiculously high levels of interest being charged in Canada.

This became an opportunity to improve the lot of the working classes and to enable the economic liberation of French Canadians by allowing them access to credit at more reasonable rates. In late 1900, Desjardins established Caisse populaire de Lévis, North America’s first savings and credit co-operative. The organization was based on his own research, which took into account the Canadian setting from a Quebec perspective. It opened on January 23, 1901, with a total of $26.40 in savings and approximately 130 members.

Desjardins originally operated the business from his house in Lévis, before establishing more caisse populaires throughout Quebec. In 1908, inspired by his work, a group of French-Canadian emigrants founded the first U.S. credit union in New Hampshire, and Desjardins attended the opening. Before he died in 1920, he witnessed the success of his ideas, as caisse populaires and credit unions spread throughout Quebec, across Canada (particularly in the country’s West), and in the northeastern United States.

Desjardins’ name and legacy live on. By the turn of the twenty-first century, Canada had the world’s highest per capita membership in credit unions. In the United States there were more than six thousand credit unions, with more than one hundred million members. Today the Desjardins Group is the largest association of credit unions in North America.

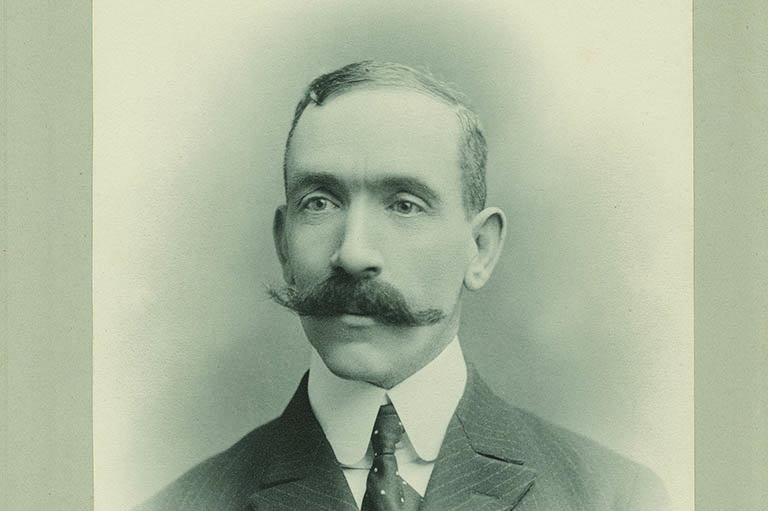

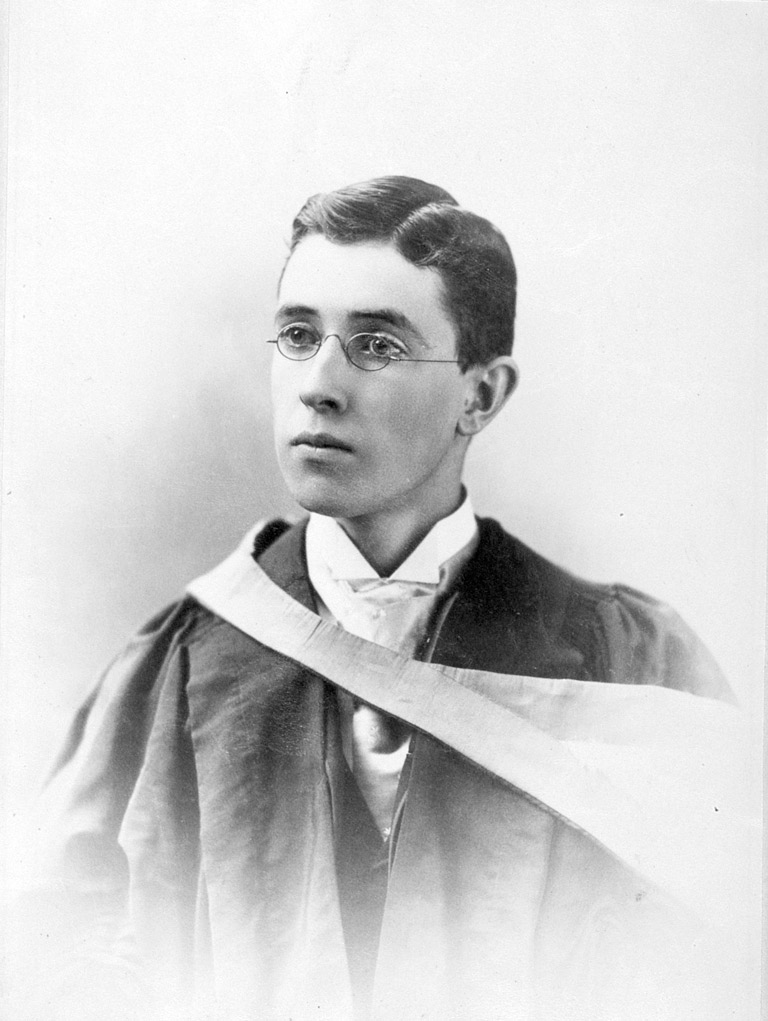

The Car-Making Master

Gordon McGregor (1873–1922)

Gordon Morton McGregor was born near Windsor, Ontario, in 1873, lived in the area his entire life, and was buried there in 1922. The Canadian auto industry was born in the Windsor area after McGregor journeyed across the Detroit River in August 1904 to meet with Henry Ford and subsequently established the Ford Motor Company of Canada Ltd.

Investors from Canada and the United States put up $125,000 (more than $2.7 million in 2017 dollars), of which $63,750 worth of stock was given to Ford Motor Company of Detroit in return for the perpetual rights to the American firm’s vehicles and technology without further cost. Ford Canada was a publicly listed company a full half century before Ford in the U.S. In its first year of operations, the company produced 114 cars. It grew slowly until production of the Model T began in 1908; then sales took off, and dividends began to be paid regularly.

As part of his agreement with Henry Ford, McGregor acquired the rights to manufacture and sell cars in the British Empire beyond the United Kingdom and Ireland. He took full advantage of this, establishing subsidiaries of the Canadian parent in India, Australia, South Africa, and British Malaya. By 1920, Ford Canada had become the largest automotive enterprise in the British Empire and produced fifty-five thousand vehicles in “Ford City” (a community founded by the company within the city of Windsor). The company accounted for nearly sixty per cent of all Canadian automobile production.

Ford was a success, along with the Canadian subsidiaries of American parents such as General Motors, because of a protective tariff. The tariff, the company’s proximity to Detroit (the world’s automobile headquarters), and the mandate to manufacture and sell globally were all factors in Ford Canada’s success. But it required the entrepreneurial eye and managerial competence of Gordon McGregor to seize the opportunity and to work with Henry Ford.

As he neared his death, McGregor could look back on his contribution to Canadian life — he had founded the largest automobile company in the country, which was by then majority Canadian-owned. In a 1922 series on Ford Canada and McGregor’s legacy, the Windsor Star wrote that, while Henry Ford had solved the world’s problem with regards to speedy and reliable transportation, “the late Gordon McGregor solved it for Canada.”

The Merchant Prince

Sir John Craig Eaton (1876–1922)

A list of the top Canadian businesspeople must include an Eaton, and I assumed that I would be writing about the legendary Timothy Eaton. I had many times rubbed the toe of his statue at the Eaton’s store in downtown Winnipeg, and there is no doubt that Timothy revolutionized retailing, at least in Toronto, where he opened a store on Yonge Street in 1869 that followed three fundamental policies: one price, cash only, and goods satisfactory or money refunded.

By 1884, he had established mail-order service using catalogues. In 1890, he started manufacturing, and in the 1890s he established buying offices in London and Paris.

As important as these innovations were, the T. Eaton Company became a household name in Canada because it was the first department store to move beyond its home city roots and establish a national chain. But as Joy Santink has written in Timothy Eaton and the rise of his department store, the senior Eaton had misgivings about managing a store from a distance. It was his third son, John Craig, who was largely responsible for establishing the company’s first branch store in Winnipeg in 1905. The store was an immediate success.

Within a few months of opening, the number of employees had to be increased from seven hundred to one thousand, and within two years a sixth floor had to be added. Its success was prophetic of the future, when the company would become “Eaton’s of Canada.”

John Craig Eaton was born in Toronto in 1876 and died there in 1922 when he was only in his mid-forties. He was a director of the company by 1898 and at age twenty-four was his father’s right-hand man. At age thirty-one, following the death of his father in 1907, he became Eaton’s president. His philanthropic efforts — scholarships, donations to hospitals and colleges, and continued payment of salaries to Eaton’s employees who served in the First World War — earned him a knighthood.

In addition to the Winnipeg store, John Craig — the “Merchant Prince,” as he was called by some — had mail-order buildings erected in Winnipeg, Saskatoon, Regina, and Moncton. He later opened factories in Toronto, Hamilton, and Montreal. Sales increased more than fivefold between 1907 and 1921. He also opened buying offices in the United Kingdom, Switzerland, the United States, and Japan.

John Craig Eaton is one of two people on this list who are not in the Canadian Business Hall of Fame (his father is) but it was he who made Eaton’s Canada’s first national department store chain.

The Banker Extraordinaire

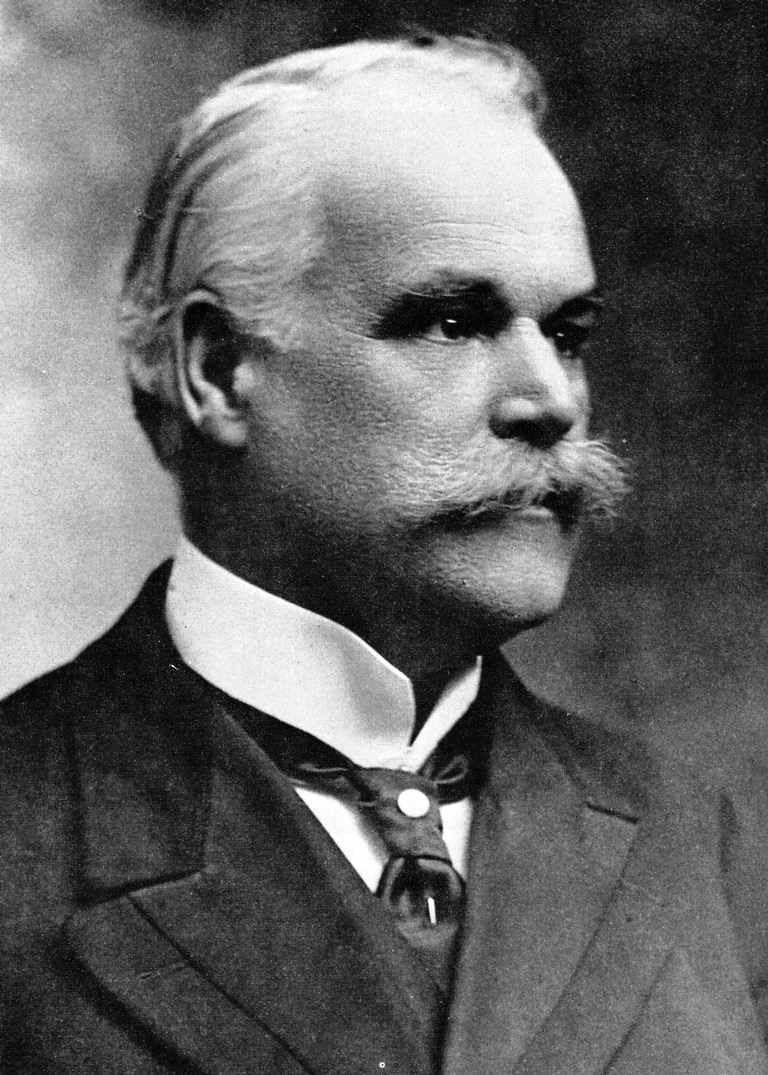

Edson Loy Pease (1856–1930)

Edson Loy Pease was born in the southwestern part of Canada East (Quebec) in 1856. In 1875, he moved to Montreal, where he joined the rapidly growing Bank of Commerce. Eight years later, the Merchants Bank of Halifax recruited Pease away from the more established Bank of Commerce. There he quickly assumed leadership roles, including opening a branch in Montreal and spearheading a drive into the British Columbia market. In addition to domestic expansion, Pease visited Cuba right after the Spanish-American War. This was a precursor to the expansion of the bank’s international activities in Latin America and the Caribbean as well as in New York and Europe.

In 1900, the forty-four-year-old Pease became general manager of the Merchants Bank. At that time it was the tenth-largest in Canada — larger than the Bank of Hamilton but smaller than the Bank of Toronto, and the head office was located in Halifax. Shortly after taking over, Pease had the name changed to the Royal Bank of Canada, and in 1907 he moved the head office from Halifax to Montreal. The following year he recruited Sir Herbert Holt, the most powerful businessman of the day, into the role of president. It was a largely titular role but was important from an image perspective.

Pease then complemented the bank’s organic growth strategy with a series of mergers. Between 1910 and 1918, the Royal Bank acquired banks in Halifax, Quebec City, Toronto, and Winnipeg. Unlike other banks’ acquisitions, those made by the Royal Bank contributed to substantial growth. By 1910, it was the thirdlargest in Canada; by 1920, it passed the Bank of Commerce to become number two; and with the 1925 merger, conceived by Pease, with the Winnipeg-based Union Bank, the Royal Bank became Canada’s largest.

During the First World War, Pease served as president of the Canadian Bankers Association. In that role he looked favourably on the notion of the creation of a central bank. As Duncan McDowall has written in his history of the Royal Bank, “the term ‘revolutionize’ cannot usually be applied to Canadian banking’s careful evolution, but Edson Pease had forced the pace of change more than any other Canadian banker.”

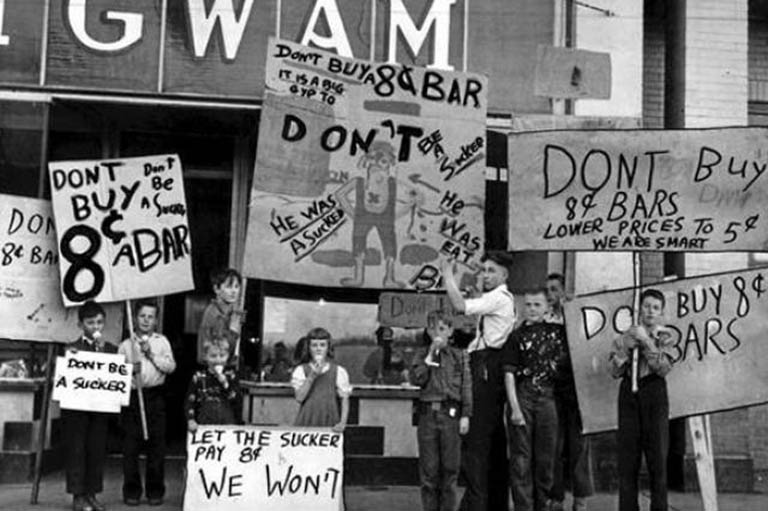

The Distilling Giant

Samuel Bronfman (1889–1971)

Samuel Bronfman was born in imperial Russia in 1889 but arrived on the Canadian prairies in the year of his birth. His family lived in what is now Saskatchewan when it was still part of the Northwest Territories and then in Brandon, Manitoba, and Port Arthur, Ontario. Bronfman went into the family business — owning hotels — with his purchase of the Bell Hotel in Winnipeg in 1912.

With the introduction of prohibition in Manitoba in 1916, the Bronfmans got into interprovincial mail-order sales of liquor. Four years later, the United States passed the Volstead Act, which provided an opportunity for exports to the much larger American market. Since the mid-1850s, Canadians had been good at distilling and selling whisky, and a number of well-known firms saw the opportunity created by prohibition — but the Bronfmans were the best. The federal government went along with the distillers because it could collect excise fees on their sales.

By the mid-1920s, the Bronfmans had moved their head office to Montreal — in the province thought least likely to adopt prohibition. They purchased a defunct U.S. distillery and brought it back to Montreal. At the same time, Samuel Bronfman went to Glasgow, Scotland, and signed a deal with Distillers Corporation. Shortly after that, in 1928, he acquired the Joseph E. Seagram and Sons distillery in Waterloo, Ontario.

As it became apparent that U.S. prohibition would not last forever, the Bronfmans’ strategy for that huge market came to be based on three principles: acquiring existing inexpensive U.S. distilleries, rather than building anew; producing “blended” whisky; and emphasizing quality but also moderation. By the mid-1950s, Samuel Bronfman had one third of the American market and had surpassed such venerable Canadian companies as Imperial Oil, the T. Eaton Company, and the Canadian Pacific Railway to become the second-largest nonfinancial corporation in the country, after General Motors.

He didn’t stop there. Bronfman acquired the Chivas Regal brand, and Seagram’s expanded internationally into Europe and Japan while forming alliances in Latin America. By the time of his death in 1971, fifteen per cent of the company’s sales were outside of North America — and that percentage would grow under his son Edgar. Samuel Bronfman, the child of immigrant parents, created a great Canadian company that was becoming a global giant with a strong U.S. presence.

The Forestry Innovator

Henry Reginald MacMillan(1885–1976)

Henry Reginald (H.R.) MacMillan was born in 1885 on a small farm north of Toronto. He attended the Ontario Agricultural College in Guelph, where he learned about forestry and about creating a sustainable resource. MacMillan received a master’s degree in forestry from Yale University and, upon graduation, went to British Columbia to work in the rapidly developing forest product industry. He later joined the civil service — first in Ottawa and then in Victoria, where he was British Columbia’s first chief forester.

The First World War provided challenges for the B.C. forest industry, which relied on selling to international markets through U.S. agents. After the war, MacMillan, with backing from a British timber merchant, established H.R. MacMillan Export Company, Ltd. to develop the international sale of Pacific Coast timber products. The company expanded in the early 1920s into shipping and the manufacture of sawn lumber.

In response to competitive pressures, the company extended its operations in the mid-1930s to include plywood. It acquired extensive timber areas on Vancouver Island and began milling operations, becoming the province’s first truly integrated forest products company. From there it expanded into door manufacturing, railway-tie production, and shipping and sales.

The H.R. MacMillan Export Company was a pioneer in vertical integration, purchasing firms involved in all parts of the lumber trade. During the Second World War MacMillan’s company experienced booming business, and it expanded at an even faster rate after the war.

This culminated in the 1951 merger of MacMillan’s company with Bloedel, Stewart and Welch to create MacMillan Bloedel Limited, the largest consolidation in the Canadian forest industry. MacMillan had a larger marketing operation, and Bloedel had more timberland. The merger resulted in British Columbia’s largest lumber and pulp operation.

When MacMillan stepped down as chairman in 1956, MacMillan Bloedel was not only the largest corporation in British Columbia, it was also the largest forest products company in Canada and one of the biggest forestry industry companies in the world, exporting to Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Great Britain, and the United States. And it was as profitable as it would ever be.

Throughout his career, MacMillan retained an interest in sustainable forestry. His company inaugurated long-term planning that included reforestation.

His successor, Bert Hoffmeister, stated that MacMillan was “in every way a great Canadian, and his emotions were easily aroused when Canada’s interests were involved.”

The Empire Builder

Kenneth Colin Irving (1899–1992)

Kenneth Colin (K.C.) Irving was born at the end of the nineteenth century in New Brunswick to descendants of Scottish settlers and died in New Brunswick in the last decade of the twentieth century. In his lifetime he built a huge conglomerate that dominated New Brunswick and had a presence throughout the Maritimes, eastern Quebec, and the northeastern United States, particularly the state of Maine.

Irving’s empire-building began in the 1920s, when there was a boom in automobile sales. Car registrations increased dramatically in that decade, and the trend prompted Irving to take ownership of a Ford Motor dealership. In addition, he took on a more active role in his father’s general store by adding a gas station, as store business was suffering due to competition from Eaton’s national mail-order service.

Originally, Irving made a deal with the Imperial Oil Company. But when that fell through he established the Irving Oil Company, which eventually built an oil refinery in Saint John, New Brunswick, that is the largest in Canada today.

In the 1930s, he diversified further. Upon the death of his father, Irving took over the family lumber business. He also purchased major media outlets, which led to eventual criticism of his media monopoly. By the time of Irving’s death in 1992, his empire included oil refining, forest products, dry docks, gas stations, and media. It consisted of more than two hundred successful companies spread throughout the Maritimes, Quebec, and the eastern United States.

In New Brunswick, one in twelve residents worked for Irving’s companies, and many people in his home province stood by the phrase “K.C. Irving is New Brunswick.”

The Irving family’s holdings in its home province form what Canadian Senate investigators have called “an industrial-media complex that dominates the province” to a degree that is “unique in the Western world.”

Unlike many Canadian entrepreneurs, K.C. Irving stayed at home. Rather than expand beyond his region, he executed a strategy of dominating the New Brunswick market. This is not a strategy taught in business schools, but, according to Fortune magazine, at the time of his death Irving was the eleventh-wealthiest person in the world. The Irving group of companies was the largest single landowner in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Maine and one of the world’s largest private landowners.