Six issues for ONLY $29.95! Save almost 40% off the cover price!

Mad Men of Expo

From start to finish, Expo 67 was a story of massive crowds, endless lineups and jam-packed restaurants. While 200,000 visitors were expected for the opening, 330,000 showed up at the ticket booths. The millionth visitor went through the turnstile on day three, along with a record single-day crowd of 570,000 people. Fifty million people would flock to the site that summer, half of them Americans.

This triumph of marketing was even more remarkable since, four years earlier, the organizing committee hadn’t been able to sell the project to the Canadian public. No one knew how. “Canada had never seen a gathering of two hundred thousand people,” said director of operations Philippe de Gaspé Beaubien, who was responsible for the proceedings.

The media, particularly the Canadian media, remained negative about — and, in some cases, even hostile to — Expo 67 for a long time. Many Canadians didn’t believe that foreigners would be interested in their little “subarctic country, uncertain of its identity,” as journalist Peter C. Newman wrote. Foreigners, particularly Americans, didn’t know what they would do in Canada.

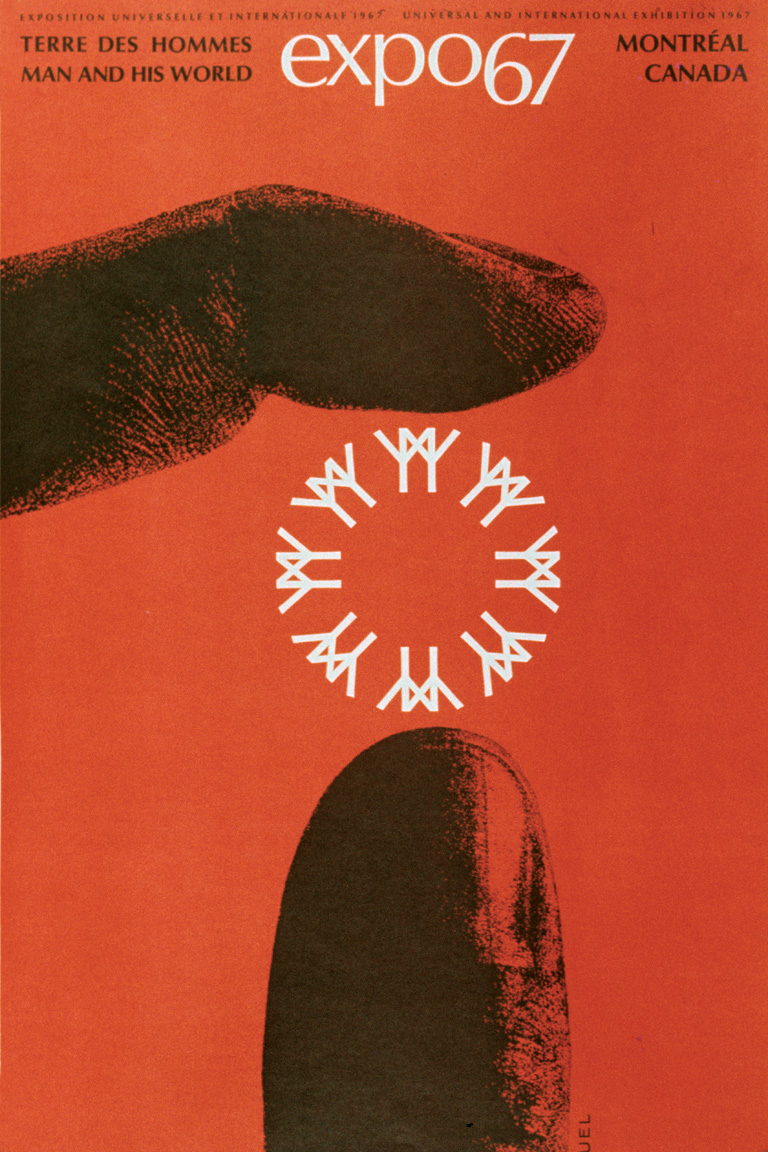

The team responsible for selling the fair made a series of brilliant decisions early on, starting with the name. Beginning in 1962, Montreal Mayor Jean Drapeau started referring to “Expo,” and the term soon caught on. “The official name was the ‘1967 International and Universal Exposition, First Category, Montreal, Canada.’ A ridiculous name! Ridiculous!” de Gaspé Beaubien said.

The Bureau international des expositions (BIE), which oversees the exhibitions, initially didn’t approve of the abbreviation “Expo,” but the organizing committee insisted. The point was not to water down the concept of an international exhibition but rather to convey to a North American audience that the event in Montreal would be something new to the continent, with an educational, cultural, scientific, and humanist calling. Eventually the BIE came around: It would be called Expo.

At a time when Expo 67 existed only on paper and part of the site was still underwater, the event organizers were already trying to give it a solid image. They erected the giant letters E-X-P-O in concrete, which could be plainly seen from the shore of the St. Lawrence River, and created many mock-ups of the site. Beginning in 1964, they organized all-expenses-paid press tours, first by helicopter when it was impossible to reach the site, then by bus and on foot. On Sundays, they even opened the construction site to the public, which also had access to a ten-storey observation tower.

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.

In addition to traditional campaigns of flyers, posters, and souvenirs, the organizers created their own information medium, Expo Digest, a newsletter with a circulation of over a hundred thousand.

They shot a series of short publicity films with major international stars of the day — French singer Maurice Chevalier, American television personality Ed Sullivan, British actor James Mason, Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin — inviting the audience to meet them in Montreal. American TV stations liked the end product so much that they aired the campaign for free.

“It was the first time that this sort of event was sold as a destination rather than just an exhibition,” said Diana Nicholson, who worked on protocol and operations and was a spokesperson for the event.

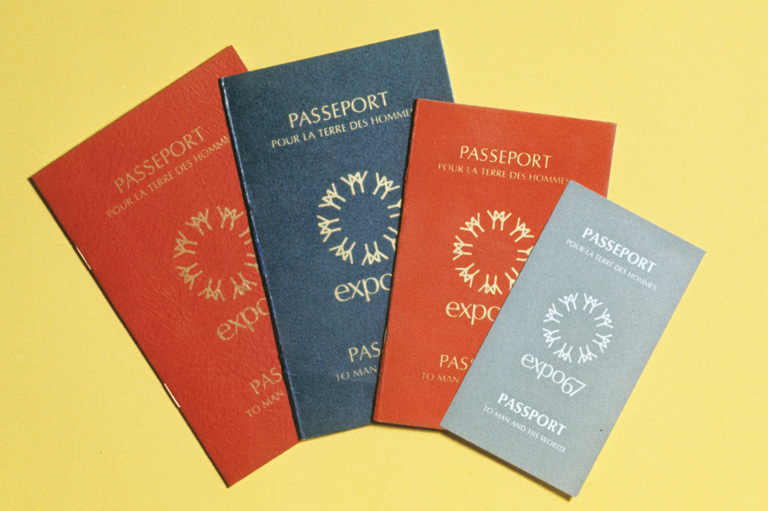

The concept of “a trip to Expo” would be pushed to the limit with the revolutionary idea at the time of a Man and His World passport. This season’s pass, which looked like a real passport, encouraged users to visit every pavilion — and have their passport stamped with the pavilion’s visa. Fifty years later, hundreds of thousands of Expo passports are still keepsakes for Canadians.

Thanks to the nearly five thousand audiovisual conferences held by the organizing committee and its representatives, they were able to recruit invaluable allies.

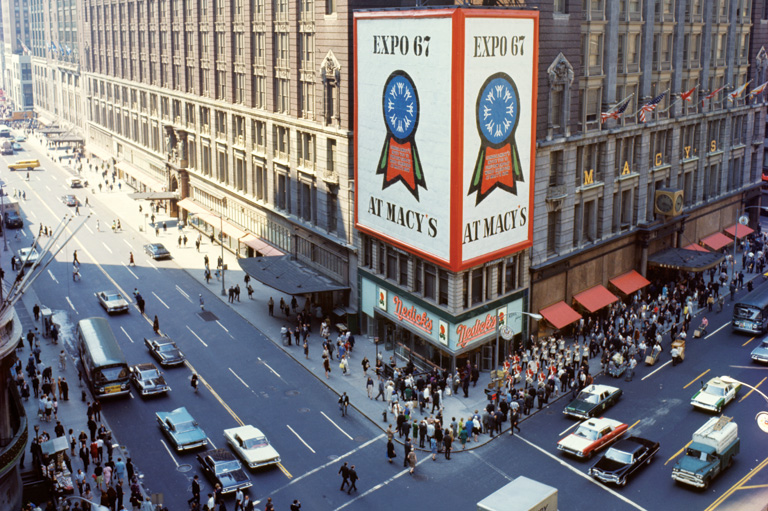

One of them earned Yves Jasmin, director of public relations, a call from the vice-president of marketing for the New York department store Macy’s in November 1965. John Blum told him point blank that he intended to build an eight-metre mock-up of Expo for display on Macy’s fourth floor. “He told me, ‘American Express will sell your passports at the display. And we are going to feature you in all our windows!’” said Jasmin.

The tipping point came at the end of 1966. The first enthusiastic articles appeared in the American press, and the Canadian press started to believe. “I saw a major shift in attitude,” de Gaspé Beaubien said. “All of a sudden, audiences weren’t resisting anymore. They wanted us to tell them how it was going and what it would be like.”

Expo’s Mad Men had pulled it off.

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement