Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

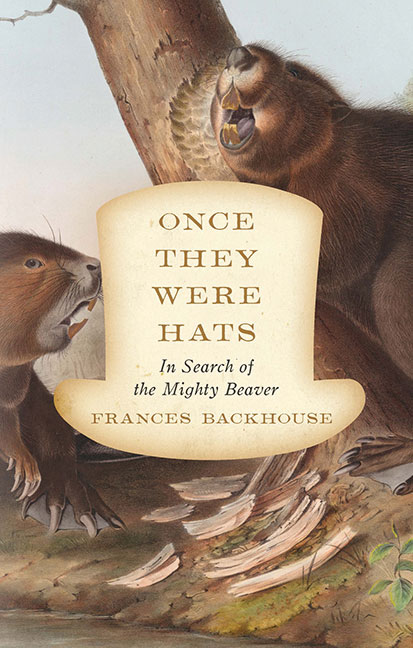

Once They Were Hats

Once They Were Hats: In Search of the Mighty Beaver

by Frances Backhouse

ECW Press

272 pages, $18.95

Our cottage neighbours are DIY workaholics: They are constantly renovating their dwellings, clearing trees, breaking trail, and building canals. We rarely hear them, except for indignant splashes when they are alarmed while swimming. But their industry is slowly reshaping our shoreline, and, without constant vigilance from park wardens and cottagers, they would alter the water levels in the lake.

So what’s new? Castor canadensis has been sculpting the North American landscape for at least a million years. By controlling the flow of water and the accumulation of sediments, beavers have filled valleys, rerouted rivers, and nudged other species down distinctive evolutionary paths. Before fur-mad strangers devastated the population, there were at least sixty million of these bucktoothed rodents spread across the continent, and they had constructed at least twenty-five million dams. In 1797, the explorer David Thompson noted a dam that was 1.6 kilometres in length while he was travelling across the West. Today, the world’s longest beaver creation is probably the 850-metre dam in a remote northern Alberta location — Wood Buffalo National Park.

The beaver has represented Canada since before Confederation (in 1851 it appeared on a postage stamp), yet most of us know little about its habits and history. Some people are under the impression that these semi-aquatic mammals eat fish; in fact, they munch on tree bark, water lily roots, and pondweed. But most of us know that any account of post-colonial British North America has to start with Castor canadensis. Furs, and particularly beaver pelts destined for the hat trade, were the first of the primary products on which the Canadian economy has always depended so heavily.

Now Frances Backhouse has blended natural history, anthropology, science, and adventure into a compelling account of our national symbol. In Once They Were Hats, she sketches the role of beavers within First Peoples’ cultures, and she discusses the beaver’s importance as a keystone species. Along the way we meet trappers, hatters, paleontologists, conservationists, elders, traders, and biologists.

Backhouse is a lively reporter, telling us all about her hike to Grey Owl’s former cabin, Beaver Lodge, in Saskatchewan’s Prince Albert National Park (“weighed down by my fully loaded backpack and sweating inside the compulsory bug shirt”) and the smell of North America’s largest fur auction (“kennel scent; butcher shop undertones; a whiff of musk”). We find her learning how to trap a beaver, cure a pelt, and face her own ambivalence about slaughtering wild animals. And she effortlessly incorporates into her captivating narrative the kind of information that snags anybody’s attention.

For example, beaver meat is premium fare because it provides three times more calories than other wild meat, such as caribou or moose, plus a fattiness that helps humans absorb the protein. It has therefore always been a critical food for indigenous peoples. However, Europeans had an additional reason to hunt beavers for food. In the Middle Ages, church authorities classified the animal’s scaly flat tail as fish, which meant it could be eaten during Lent. (I’m not sure what they did with the rest of the beaver, since the body meat remained off-limits.)

The most extraordinary aspect of the story is the beaver’s resilience. From dominating the landscape half a millennium ago, beaver populations sank as low as 100,000 at the start of the twentieth century. Concerns about extinction, and the recognition of the beaver’s important role in preserving wetlands, has allowed the population to bounce back to somewhere between ten and fifty million. In some regions, especially in the arid West, the renaissance is welcomed as a return to a healthy ecology; in others, particularly cottage country, beaver activities have catapulted the animals straight back into the feral-menace category.

But, thanks to Backhouse’s thoughtful, fascinating exploration of beaver know-how, I will not complain about the neighbours next summer. Instead, I’ll have my binoculars trained on them.